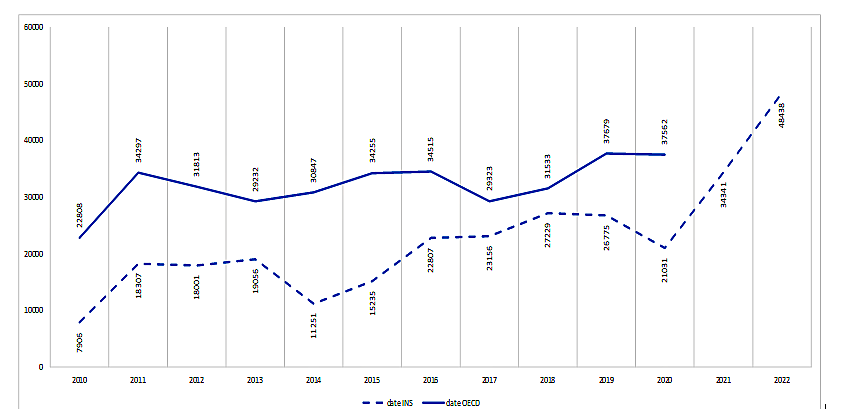

Are Romanians still leaving the country as they did in the early 1990s or during the great global financial crisis of 2008? It depends on which stream we are looking at. If we take temporary emigration for more than a year as a standard, then we can talk about a slight decline. According to data from the National Institute of Statistics (INS), in 2008, the second year after joining the European Union (EU), the number of shipments reached 217,000 in 2021, after relatively erratic fluctuations. It was and is the strongest flow of those who kept their place of residence in Romania, but chose a permanent place of residence for more than a year in another country. The second stream for which we have INS data is permanent migrants who have changed their residence. Immediately after joining the EU, the number of people who left the country permanently in 2007 was approximately 9,000. After fluctuating evolution, around the annual value of 20 thousand (Fig. 1), their number reaches approximately 48 thousand in 2022. Is it common or significant in an Eastern European context? Why this increase? From which countries are the most departures? Why

We know nothing about the flow, perhaps increasing, of migrants who leave and arrive, at short intervals, in a system of circular migration or “Euro-commutation”. We will learn more from the INS about those who have been abroad for less than a year. Their number is fixed in censuses. According to the 2011 census, this stock was about 385,000 short-term departures. Hopefully, at the local level, we will see the estimated number of short-term emigrants based on the results of the 2021 census conducted in 2022. Sooner or later we will learn, hopefully also from the INS, the details related to the temporary migration of more than a year abroad.

Currently, however, according to available data, extremely bad for such an “emigration” country (with significantly more departures than arrivals) like Romania, we will try to focus on data related to final emigration[1]. First, we will follow trends in final emigration at the national level, and then at the regional level.

A growing trend across the country?

The data in Figure 1 suggest a first affirmative answer, at least in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) version of the assessment. INS data points to a sharp increase in permanent emigration after the 2020 pandemic. If this increase is also confirmed by OECD data not yet published after 2020, the question of “why” will also have to be answered. A compensatory effect of reduced emigration in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic? maybe. However, it is equally possible that this increase is also the result of a general trend of increasing the number of those leaving the country permanently. We will try to get additional details on the topic through analysis at the regional and district levels.

With almost 38 thousand permanent emigrations from the country in 2019 and 2020 (OECD data), where does Romania stand in the context of Eastern Europe? The first answer can be obtained by converting the data on absolute emigration into relative terms and comparing them with two other Eastern European countries – Bulgaria and Poland. Having such data, it can be assumed that the indicators of permanent emigration are inversely proportional to the gross domestic product per capita from the EU average (GDP%). In 2019, GDP as an indicator of economic development was 53% of the EU average for Bulgaria, 69% for Romania and 72% for Poland (EUROSTAT data). The final level of emigration was, according to the OECD, the maximum – 1.55‰ for Bulgaria, 1.38‰ for Romania and 0.79‰ for Poland. In other words, the higher the level of economic poverty, the higher the level of permanent emigration at the country level, as a rule,.

Final emigration from Romania is relatively concentrated in terms of destination.In 2019, a year before the pandemic, more than two-thirds of the last shipments from Romania (68%) were destined for four countries – Italy, Germany, Great Britain and Spain. With three additional destination countries – the United States of America, Belgium and France – 84% of the final 2019 emigration from Romania has been reached[2].

Escape from Moldova or from poor micro-regions where there are many migrants abroad?

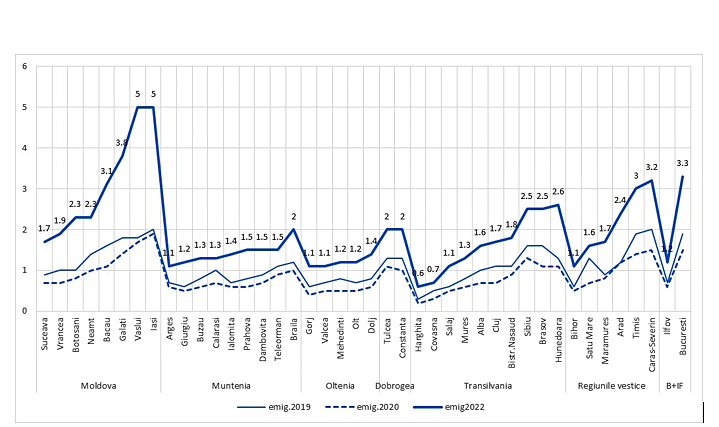

The graph in Figure 2 shows that this will be an outflow of those who left the country permanently, mainly from the historical region of Moldova, or more precisely, from the counties of this region. The trend is noticeable especially for 2022. The COVID-19 pandemic appears to have contributed to a decrease in permanent departure from all countries of the country. To make things clearer in a cause-and-effect manner, we need data at the local, commune or city level. Unfortunately, this data is not public. We will try to deal with them at the district level, referring to the records of 2022 (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Rates of final emigration from Romania by country of origin, 2022. Data source: National Institute of Statistics (INS), TEMPO database. Calculations and graphs DS.emig.2019 – the level of permanent emigration (= permanent departures from the district per 1000 inhabitants), 2019. Emig.2020 and emig.2021 – indicators of permanent emigration from the district for the reference years.

If we focus on the analysis of all 42 counties, including Bucharest as a county, the picture becomes more nuanced. We considered not only the rate of permanent emigration for each county in 2022, but also the county’s human development rate in 2018, the intensity of out-migration in the 2002 and 2011 censuses, while controlling for the largest historical county-owned regions, and the degree urbanization of counties.

We do not present the analysis here in detail so as not to overload the material with technical references[3]points to two types of county effects on the rate of permanent emigration, namely the level of development-poverty and, on the other hand, the counties’ experience of out-migration. The most intensive final departures are recorded in the poorest countries, where there is a tradition of temporary, long-term and short-term departure or emigration abroad. In other words,the strongest final emigration was not just from the historical region of Moldova, but from the poorest counties of the country, with a tradition of final emigration. – Read the entire article and comment on Contributors.ro

Source: Hot News

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.