In Japan, survivors of a nuclear disaster are called hibakusha.

Will Matsuda is not one of them. He was 20 years old and living in Honolulu when Paul Tibbets, an Enola Gay pilot, dropped the “little boy” bomb on Hiroshima. The bomb leveled the city and killed over 100,000 people. Of her family, only one uncle managed to survive. The diary says August 6, 1945.

Scientists have calculated that during the eruption, the earth’s temperature fluctuated between 3,000 and 4,000 degrees Celsius, which is enough to melt a person.

“When I think about this day, I imagine my family having breakfast at the table, and turn to dust in the windMatsuda says.

She herself has never been martyred in Hiroshima, but she strongly feels the need to touch this part of the family history.

“I’m looking for what’s left, a family heirloom, a letter, a piece of jewelry,” says the photographer and writer in an article in the New York Times.

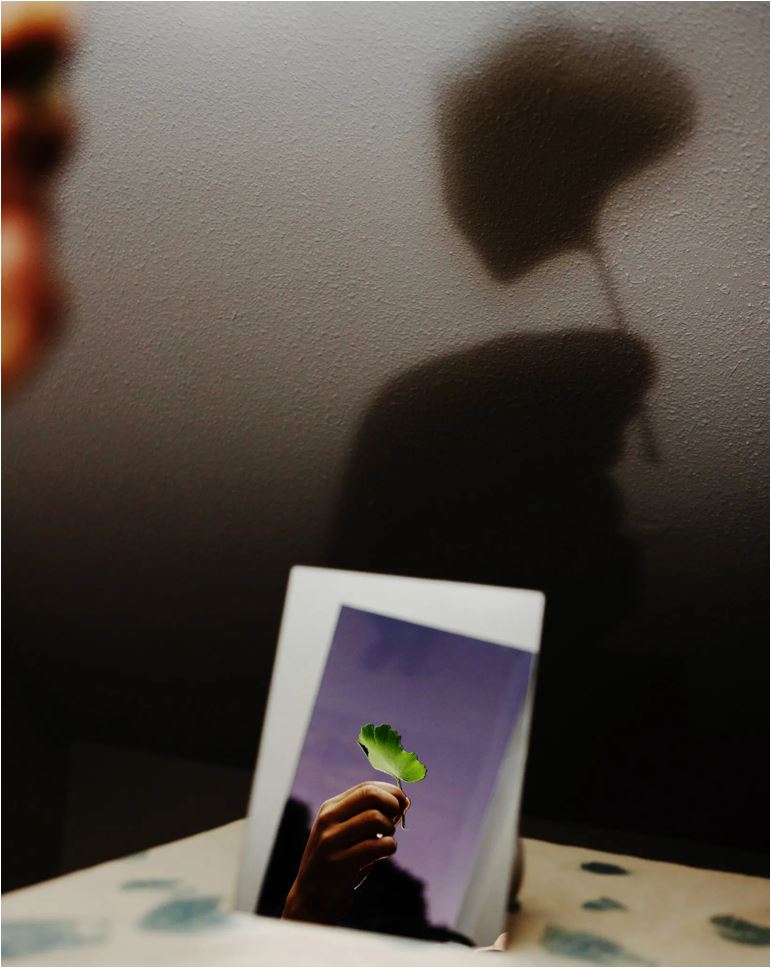

“Oddly enough, the things that give me the most meaningful connection to Hiroshima are not objects, but living, breathing things: they are trees. Gigo, to be precise,” he admits.

Gingko, endemic to China, is one of the oldest and most durable trees in the world. They managed to survive it asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs on the planet. And it was one of the few living creatures that “survived” when the incendiary wave of the first atomic bomb that fell on Earth swept over Hiroshima.

Some of these original trees still stand proudly today. They are called hibakujumoku and, like human survivors, they have scattered “descendants” around the globe.

Hideko Tamura Schneider, a hibakusha from Hiroshima, was ten years old when the atomic bomb killed her mother, best friend, and many relatives.

In 2003, he moved to Oregon, and in 2017, in collaboration with Himbakujumoku’s Green Legacy Hiroshima, began transporting “surviving” giko seeds to the US. snyder planted a total of 51 seeds which he calls “the trees of the world of Hiroshima”.

“I can’t raise my mother. Even my cousin. But a tree can,” she said in an interview with NBC in 2019.

In recent months, Matsuda, who is a permanent resident in Oregon, visits these trees of the world. He waters them, takes pictures, touches their tough leaves. “I thank them for being here and tell them that I am here too,” he says.

Matsuda uses light and shadow to tell stories.

“Each shadow tells the story of the body: the body that rested, the body that danced, watered the flowers, the body that hurt hugged another, the hall of bodies, the market of bodies shopping, vegetables and oil. and toilet paper and shoes, about a street full of bodies on the way home, about a neighborhood of bodies that lived so close together that they knew each other very well,” he describes and concludes: “A city full of bodies. full of corpses.

Her 96-year-old grandmother planned to return to Hiroshima this fall, but her failing health will likely prevent her from doing so. However, Matsuda is determined to travel alone, even if she doesn’t accompany her grandmother.

“I will visit the place where our family once lived and see Himbakujumoku, the tree of mothers and grandmothers that I know so well. I will feel their leaves and I’ll tell them we made it, we stayed alive“.

Source: New York Times.

Source: Kathimerini

Anna White is a journalist at 247 News Reel, where she writes on world news and current events. She is known for her insightful analysis and compelling storytelling. Anna’s articles have been widely read and shared, earning her a reputation as a talented and respected journalist. She delivers in-depth and accurate understanding of the world’s most pressing issues.