“I’m from the government and I’m here to help” were named by US President Ronald Reagan as the 9 scariest words in the English language, writes Radu Krachun in his blog. In his opinion, the state should attract less financial resources and leave more money to the private sector.

To an outside observer who believes that Romania’s budget has the lowest budget revenues compared to GDP in Europe, it seems that Romania is also practicing the theory of minimization of state apparatus and public expenditure. Which is terribly untrue.

And this is precisely the paradox of Romania. We have budget revenues of the minimum state and expenditures of the maximum state. Despite the fact that budget revenues are the lowest in Europe in relation to GDP, budget expenditures are caused by a hypertrophied budget apparatus and inefficient allocation of resources, mostly aimed at social benefits and wage payments.

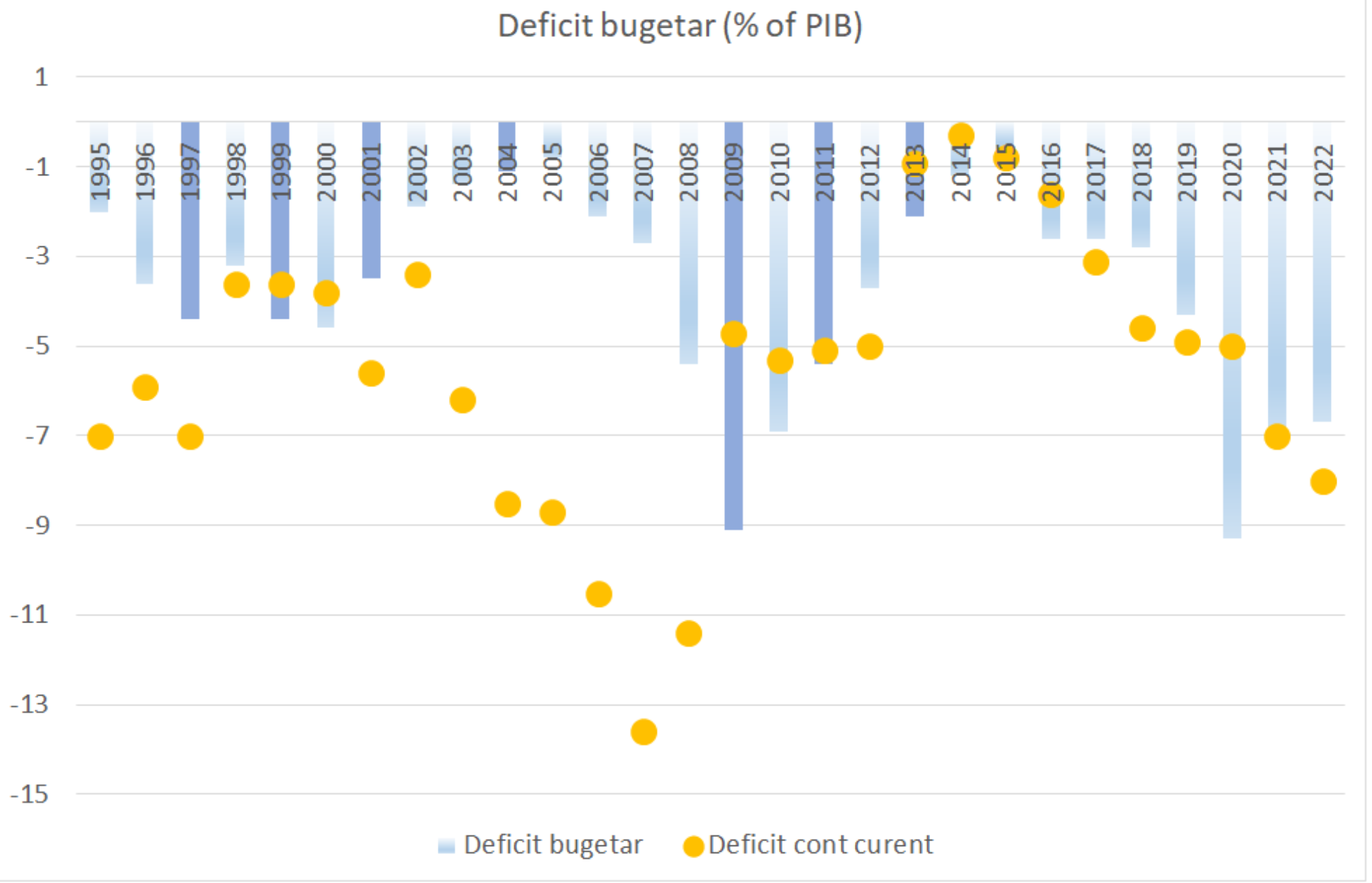

The chronic inability to increase revenue through collection is the explanation for Romania’s budget deficit in recent decades

Without irreversible external financing of the last decades, the country would be doomed to underdevelopment in terms of the structure of budget expenditures.

The chronic failure to raise revenues through collection is the explanation for the budget deficit that Romania’s budget has faced in recent decades: too high costs for such low revenues. And fixes were not only not easy, but simply impossible without outside help/pressure.

Because when you carelessly go to the “edge of the economic abyss”, quick corrective measures are needed. And they can’t raise the levy, which takes years and political consistency. The only quick fixes remain spending cuts and, above all, tax increases. And for such unpopular events, a scapegoat is needed so that they are not settled politically. And here comes the problem…

As we show in the commentary “Are we going back to the IMF?”, all the fiscal adjustments of the last decades have been carried out only with the assistance of the IMF and, more recently, the EU.

The shaded columns below show the years when Romania signed stand-by agreements with the IMF. Note that they were always signed in the context of large imbalances that needed to be corrected and political costs that needed to be externally imposed.

In fact, this is the source of the current struggle: to take responsibility for the first time to keep the budget afloat without blaming the IMF or the EU. Can we make this premiere? The signals are not inspiring when you consider the confusing messages we see in the public space.

In public discourse, fiscal changes that are necessary in principle are constantly mixed with those that are necessary from an economic point of view.

The adjustment of 20 billion lei mentioned by the Minister of Finance cannot be carried out without affecting investments, salaries, the number of employees in the public sector or without raising taxes. The savings provided by alternatives excluded from such measures are tiny compared to the $20 billion needed to reduce the deficit.

Second, in public discourse, fiscal changes necessary in principle are constantly mixed with those necessary from an economic point of view. Either the illusion is created that major economic imbalances are being resolved through fundamental adjustments, or, on the contrary, if the impact of changes caused by ethical considerations does not have serious consequences, they are not a priority.

For example, reducing special pensions will not solve the problem of 20 billion. Which does not mean that special pensions do not need to be reviewed, but the reason is more fundamental than economic.

On the other hand, the fundamental debate about the progressive payroll tax is obviously subject to more careful analysis. A public speech explains how a progressive payroll tax will allow us to build highways, invest in education or health care.

No one provides figures regarding additional revenues to the budget from progressive taxation. Explanation: they are far from effective

Paradoxically, no one cites figures regarding additional revenues to the budget from progressive taxation. The explanation is simple: they are far from effective. Moreover, when the flat tax was introduced in 2005, collection volumes increased compared to the previous period when the progressive tax was applied.

If one really wants a fiscal system that encourages social solidarity, one should promote not a progressive tax on wages, but a rethinking of the wealth tax system. After all, the rich, whom some want to tax more, didn’t get rich from their salary… And I wonder if we shouldn’t start the so-called solidarity with those broad social and professional categories that are now exempt from paying taxes?

The temptation to justify a progressive tax by comparison with countries like Germany is interesting. The truth is that we have too little in common with Germany or other developed Western countries to warrant such a comparison. And the scale of tax evasion is certainly one of the main differences.

Instead, we are much closer in terms of economic development and culture (and unique quota) to Bulgaria, but we ignore it. Even if (or because) it is the champion of VAT collection, while Romania is the European champion of VAT avoidance. If Bulgaria had a solution, then Romania certainly does. Provided that they are wanted.

Finally, the need to reduce the budget deficit is presented as a constraint imposed by the EU through the excessive deficit procedure. The truth is that the reduction of the budget deficit is caused primarily by internal constraints: high inflation and a large current account deficit.

Of course, a general increase in taxes would also solve the problem. And they would reduce purchasing power,

We know the short explanation for inflation: too much money chasing too few goods and services. As long as excess budget spending only stimulates consumption, rather than stimulating the economy to increase the supply of goods and services, budget deficits will fuel inflation and imports.

Of course, a general increase in taxes would also solve the problem. And they would reduce purchasing power, consumption, inflation and the external deficit. Except that it would mean a general decline in living standards instead of clearly targeting budget surpluses and dodgers.

To understand the urgency of the fiscal problems facing Romania, add to the existing fiscal pressures the rising costs of financing the foreign debt and the rapid aging of the population, which will culminate in the end of the “decrees”.

For our comfort, even if for different reasons, we are not alone in this fiscal fantasyland, as an editorial in The Economist calls it, commenting: “Governments are stuck in a fiscal fantasyland and must find a way out before disaster will happen.”

Source: Hot News

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.