In his opinion, Ermoupolis is the most beautiful Greek city. “Because its beauty is concentrated, not diffused, a pure 19th century neoclassical city despite the damage done to it. Many ruined factories testify to its industrial development, its imposing town hall, designed by Ziller, testifies to the wealth and inclination towards nobility of the citizens who ruled it, while the Italian-style theater paraded mainly foreign, but also Greek troupes.

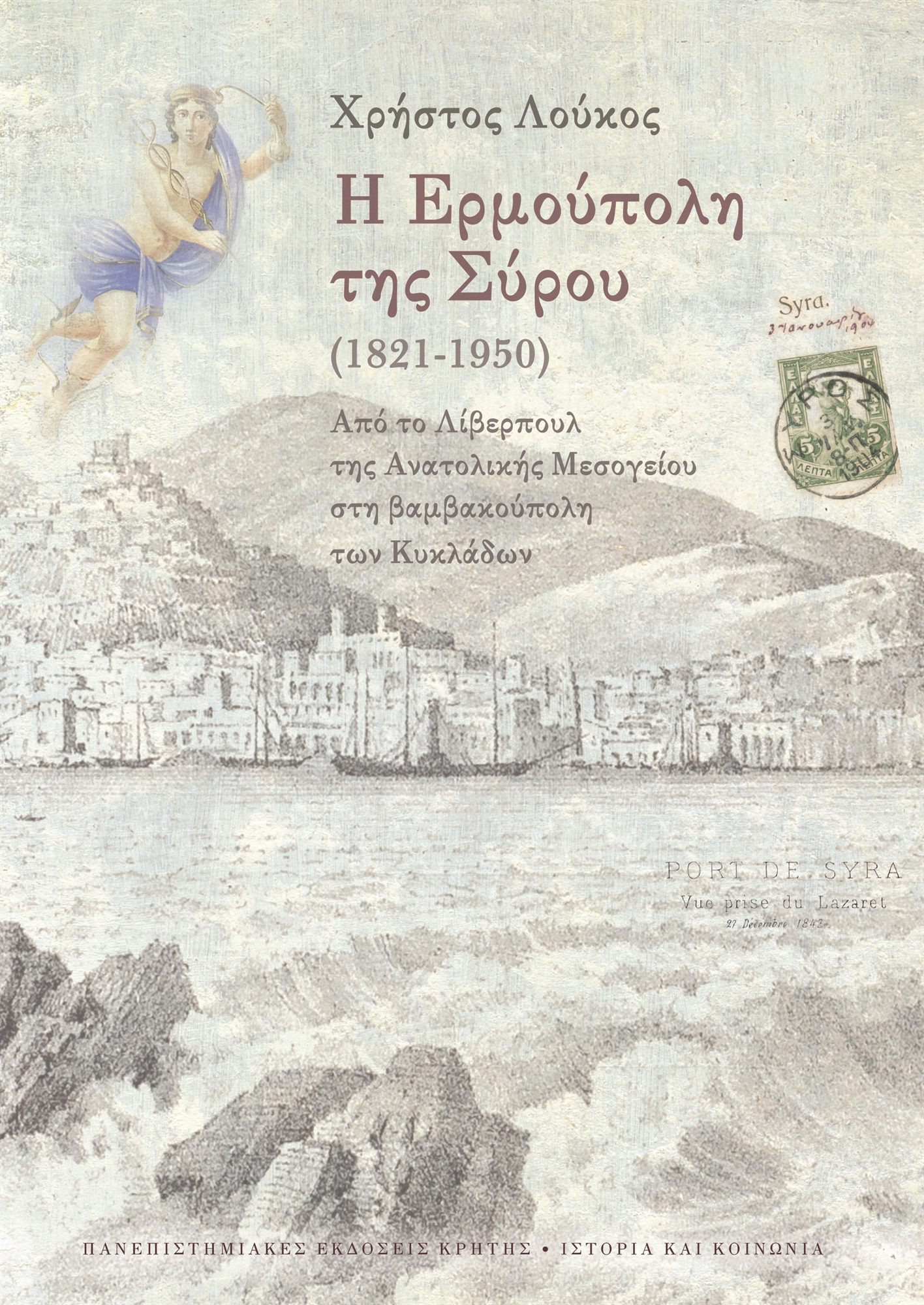

Our conversation with the historian Christos Loukos, professor emeritus at the University of Crete since 2012, founder and active member of the Society for the Study of New Hellenism (EMNE), takes place on the occasion of the recent publication of his book Hermoupolis Syros (1821-1950). From Liverpool of the Eastern Mediterranean to the Cotton City of the Cyclades” (published by PEK).

It is the fruit of years of study that began with personal interest – his wife is from Ermoupoli and she introduced him to the city in 1972 – and was closely connected to his scientific interests along the way. With members of the newly formed EMNE and “with the impulse of youth” – as he comments – they decided to take apart the city’s municipal archive, freshly brought out of obscurity. “His wealth of information about almost all aspects of the life of the inhabitants was the first, unclear at the beginning, prompting for me to take up the history of Ermoupolis. This motivation was further enhanced when I was in Paris between 1982 and 1985 and saw the progress that had already been made in the field of urban history in France as well as in other countries,” he explains.

In his “Foreword” Mr. Loukos writes about “the charm of creating a city from scratch in the crucible of the Greek revolution”. Thus, Ermoupolis is a creation of 1821. “Its foundation simultaneously demonstrates the drama of the refugees who fled to Syros and their dynamism, thanks to which, in a few years, they have made their city an important transit center for the wider region. for trade between West and East,” explains the historian.

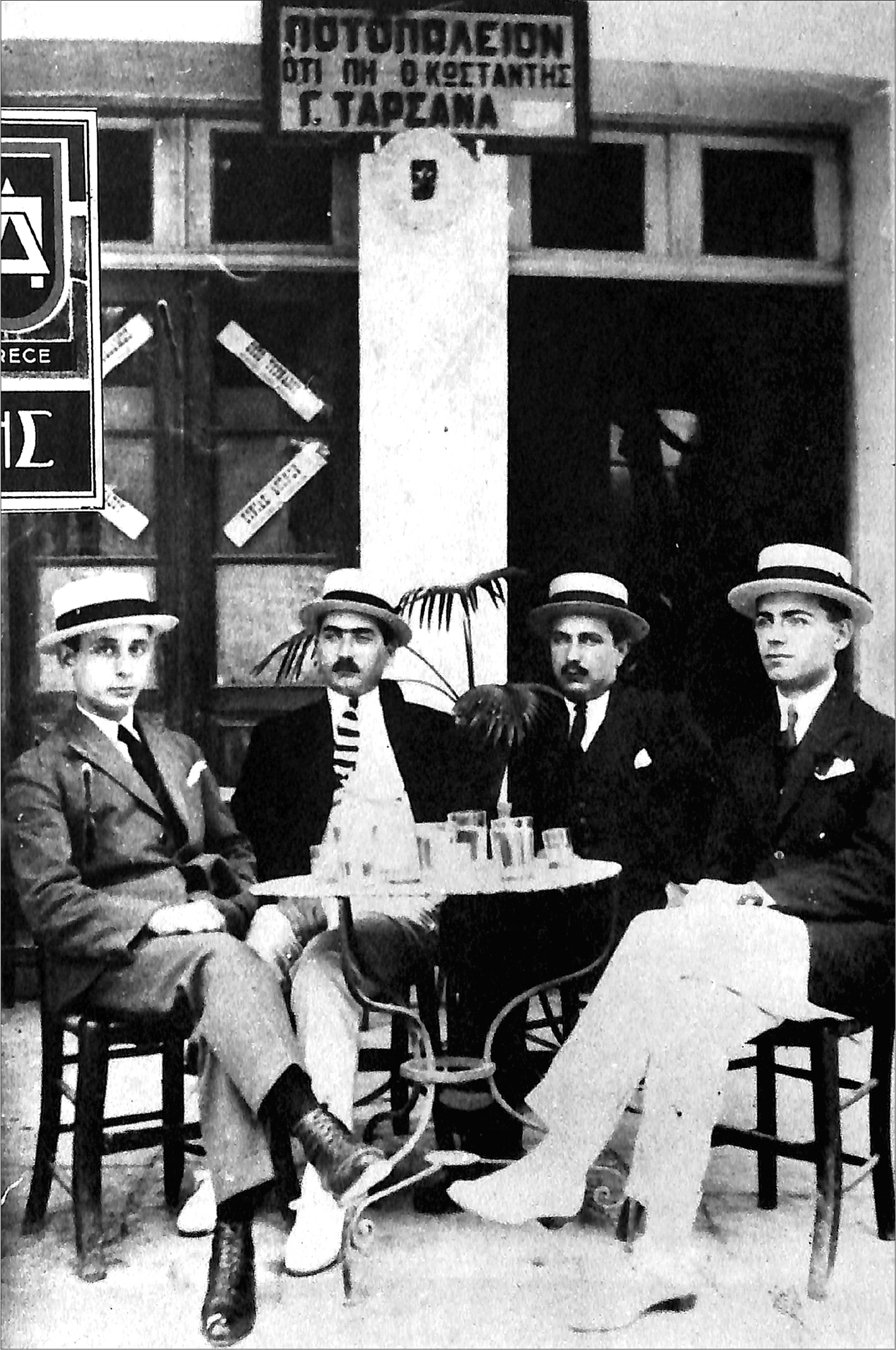

For the next 40 years, it was the second city of the Greek state after Athens in terms of population and the most important economic center. He saw for the first time the social differences between the many workers in the port, in its shipyards, in its crafts and industries, and the bourgeoisie, which quickly rallied and shaped its physiognomy.

“His creation demonstrates both the drama of the refugees who fled to Syros and their dynamism,” says historian Christos Loukos.

But since the 1870s, the decline began and social contrasts intensified. The strike of thousands of shipyard and tannery workers in 1879 was the first organized in the Greek state. How did the population of the city react to the new conditions that changed their lives?

“As for the future of the city, the initiative of some capitalists to turn the economy of Ermoupolis towards the cotton industry stands out. The factories established from the late 19th century absorbed most of the population, who were unemployed or underemployed. Thus, it was possible to avoid a vertical fall and preserve a secondary, but important position in the country outside the city,” Mr. Lukos replies. With the transition into the twentieth century, new labor relations emerged as the working class became aware of its social role.

Ermoupolis did not escape the political and social tensions of the split and state volatility of the interwar period. Class inequalities sharpened, poverty and its consequences – especially during the crisis of the 1930s – were serious. However, the arrival and settlement of several thousand Asia Minor refugees demographically stimulated the city and, despite initial adjustment difficulties, provided other forms of sociability and quality of life.

“An important parameter of this period is the more courageous participation of the Catholic inhabitants of the island in the events of the city,” the historian emphasizes. “Isolated on the hill of Ano Syros, after the founding and development of Ermoupolis, they tried to preserve their uniqueness from the risk of being assimilated by a neighbor full of dynamism. However, from the beginning of the 20th century, and when the occupation of agricultural production in the rest of the island, which largely belonged to them, reached its limits, the textile factories of Ermoupolis began to work mainly women and girls, while permanent settlement increased the number of Catholic residents. in the city and their desire to be equal citizens with Germans at all levels.

During the occupation, the city lost a quarter of its inhabitants from starvation, that is, proportionately more victims than Athens. The difficult years after the Decembrians and the Civil War also marked Syros. Trying to restore the thread of normal life was very difficult. By the end of the 1940s, the last factories were closed. For many, the only way out was to emigrate to Athens and Piraeus.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.