Perhaps few people know, but on September 27, an incident occurred in the London financial market, from which important lessons emerge. In short, on Friday, September 23, the new Prime Minister of Great Britain announced a plan to cut taxes, as well as a plan to support households in the face of an energy price shock. Tax breaks were estimated at around £47bn, while spending on defense programs would be around £110bn. Put simply, such a policy would mean a £47 billion reduction in revenue and a £110 billion increase in spending, meaning an additional deficit of £157 billion. The announcement sent the financial market into a frenzy, spooked by the additional budget deficit and the potential inflation it could cause, with the pound sterling and British bonds plummeting.

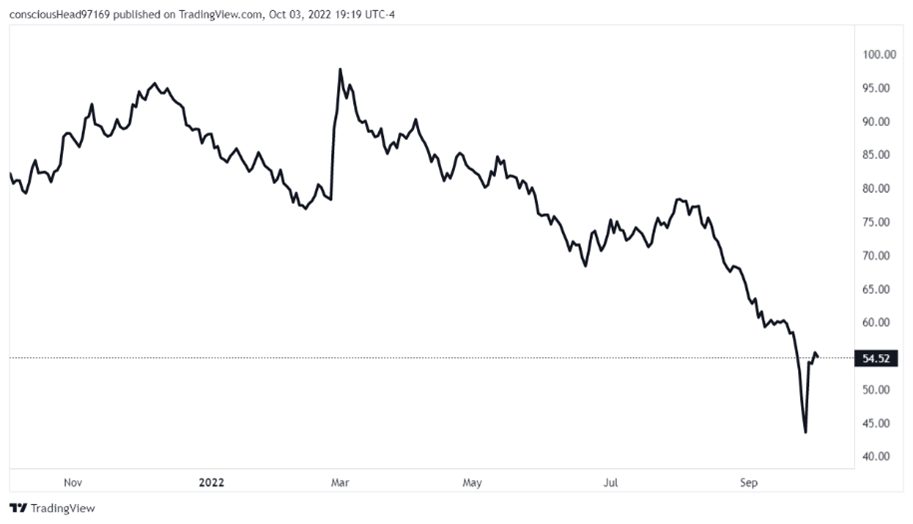

The graph shows the sudden fall in the pound sterling and the subsequent recovery after the intervention of the Bank of England.

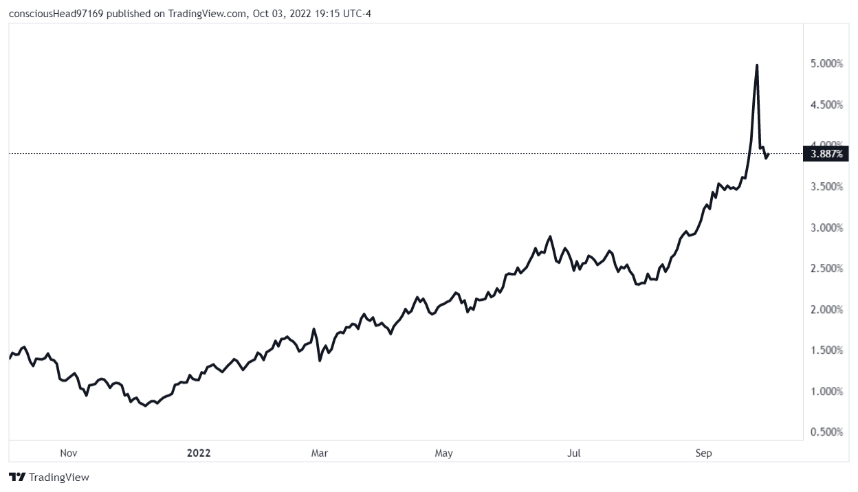

Note the sudden increase in expected bond yields (yields) at the same time as the GPB/USD exchange rate declines. This is normal as bonds have a fixed value denominated in pounds sterling. Bondholders will try to offset losses from inflation. Since interest and value are fixed, this means buying bonds in the market at less than par plus interest. On the other hand, as a result of a significant increase in the deficit, there is an additional risk of the issuer’s insolvency (default), which is also covered by an increase in the expected return.

There is a sudden decrease in the value of bonds, which is a consequence of the insecurity of investors, additional risks generated by a sudden increase in the budget deficit of Great Britain.

The largest holders of bonds are British pension funds. For virtually every pound saved for retirement, pension funds borrowed two pounds and bought three pounds worth of bonds. If the value of bonds falls below a certain value, pension funds are obliged to sell bonds to repay borrowed amounts (margin call), otherwise they risk repaying the loan at the expense of deposited pensions. But under such market conditions, a sudden and very large increase in the supply of bonds would most likely not have many buyers, which would lead to a complete collapse of the market, and with it, to the disappearance of pension funds. Under such conditions, with falling bond values, financing the UK’s deficit would be impossible, leading to total chaos.

The situation was saved by the BoE (Central Bank of England), which announced the purchase of unlimited amounts of bonds (Quantitative Easing). The value of bonds withdrawn from the market is estimated at 67 billion pounds. The bond market has stabilized and so has the pound sterling for now. The problem is that this transaction is happening just as the Bank of England was about to start selling the bonds in its portfolio and raising interest rates to stabilize inflation. In other words, in the medium to long term, while the measure stabilized the market and absorbed the shock, it set England on a path to accelerated inflation and delayed the long-term return to normal inflation.

What is the meaning of the story? What should Romanian governors learn?

The first obvious lesson is that you need to be especially careful about communication, and in particular about financial policy. Markets are nervous, and shocking statements or announcements of shocking measures, a great propaganda tool for those in power, can have completely unforeseen dramatic consequences. The market is quite volatile, energy shocks and war have shaken confidence, so any statement of intent, even if it is not yet legally binding or accepted policy, can cause a disproportionate and very negative reaction.

The second lesson is more difficult, ideologically sensitive. Private pension funds are very vulnerable to inflation. The relatively good British model clearly demonstrated its vulnerability to inflationary shocks. This was a good model as long as interest rates tended to zero and inflation was within optimal parameters. One reason is that UK pension funds can use financial leverage (borrowing) to multiply the profits needed to cover pension increases. The new reality is different, and new solutions will have to be sought. With high inflation comes high interest rates, which dramatically reduces investment opportunities for pension funds.

Lesson Three: MMT is dead. The state cannot work indefinitely with large deficits financed by currency issues. Issuing government deficit money will inevitably lead to inflation, which will automatically make government bonds unattractive to investors unless they are covered by higher interest rates. The economy is self-regulating through the crisis. What scares me is that the government deficit crisis has no intervention mechanism. Who saves the states? I am not talking about states that are economically smaller than the average multinational corporation.

The fourth lesson is the reaction of the financial market to the content of the plan of the new British Prime Minister. Limiting the price of energy from the pen of the government cannot solve the energy crisis. Whether it is the British government or any other government, and I say the European Union, they are not stronger than the laws of economics. Price caps without coverage lead to shortages, and the reality is that no government can afford to finance the energy price gap. The only solution, I say, is to increase and diversify our energy supply. In Romania, perhaps a revision of the PNRR and the restart of coal-fired power plants would be a realistic solution to combat the inflationary situation. Also, if you take the inflationary effect into account, the PNRR could do more harm than good, in fact I can’t imagine how an amount the size of the PNRR would be absorbed in Romania without the prices skyrocketing.

Advertising

We may think that Britain is a special case, we may say that in fact their situation has worsened due to Brexit, that if we are to agree with some critics, British governance has been of questionable competence at best, but what has happened in Britain is merely a symptom international disease. And the decision to restart QE in an inflationary environment is only a temporary solution, which creates two very difficult problems for the Bank of England and the UK.

There are voices that say that what happened in the EU will happen in all developed countries, maybe also in the USA. It seems that stopping inflation at the international level will be a painful, difficult phenomenon, and it is likely that the economic crisis will not be avoided at the global level.

The specter of a serious European and world crisis is intensifying. Romania could be protected to some extent because it has a variety of natural and energy resources, but only to a certain extent. Bond and currency volatility is high at alarming levels. Read the whole article and comment on Contributors.ro

Source: Hot News RO

Robert is an experienced journalist who has been covering the automobile industry for over a decade. He has a deep understanding of the latest technologies and trends in the industry and is known for his thorough and in-depth reporting.