The unique advantage of Thessaloniki is its Byzantine heritage. Mosaics and frescoes in fifteen temples, masterpieces of the “second-class” city of the empire, confirm its prominent position in the Byzantine world as an intellectual center where all the artistic movements of Constantinople found expression.

To understand the superiority of Thessaloniki, it is enough to mention that the iconography of its temples, UNESCO World Heritage Sites, indirectly reflects the image of the temples of the reigning city, where – except for the painting in the church of the Monastery of Chora – very few examples have survived. Given that today, due to the transformation of its monuments into Muslim mosques (Agia Sophia, Chora Monastery, Panagia Pammakristos, Agii Theodori), the frescoes and mosaics are no longer visible, the temples of Thessaloniki are a unique testament to the art of interaction between two great centers.

Iconography in the main temples of Thessaloniki also suffered during the Ottoman era. The overlaying of frescoes for their use as mosques resulted in the failure to preserve the entire original painting. However, a large part of it has been preserved, giving today a complete picture of the monumental painting of the 9th-15th centuries (867-1430). No other city – apart from Mistra and Kastoria – has so many high-quality works of art preserved over such a long period of time.

Dynasties of Macedon, Komnenos and Paleo-Logos: the heyday when the ideas of humanism and classical education had a great influence on art and science.

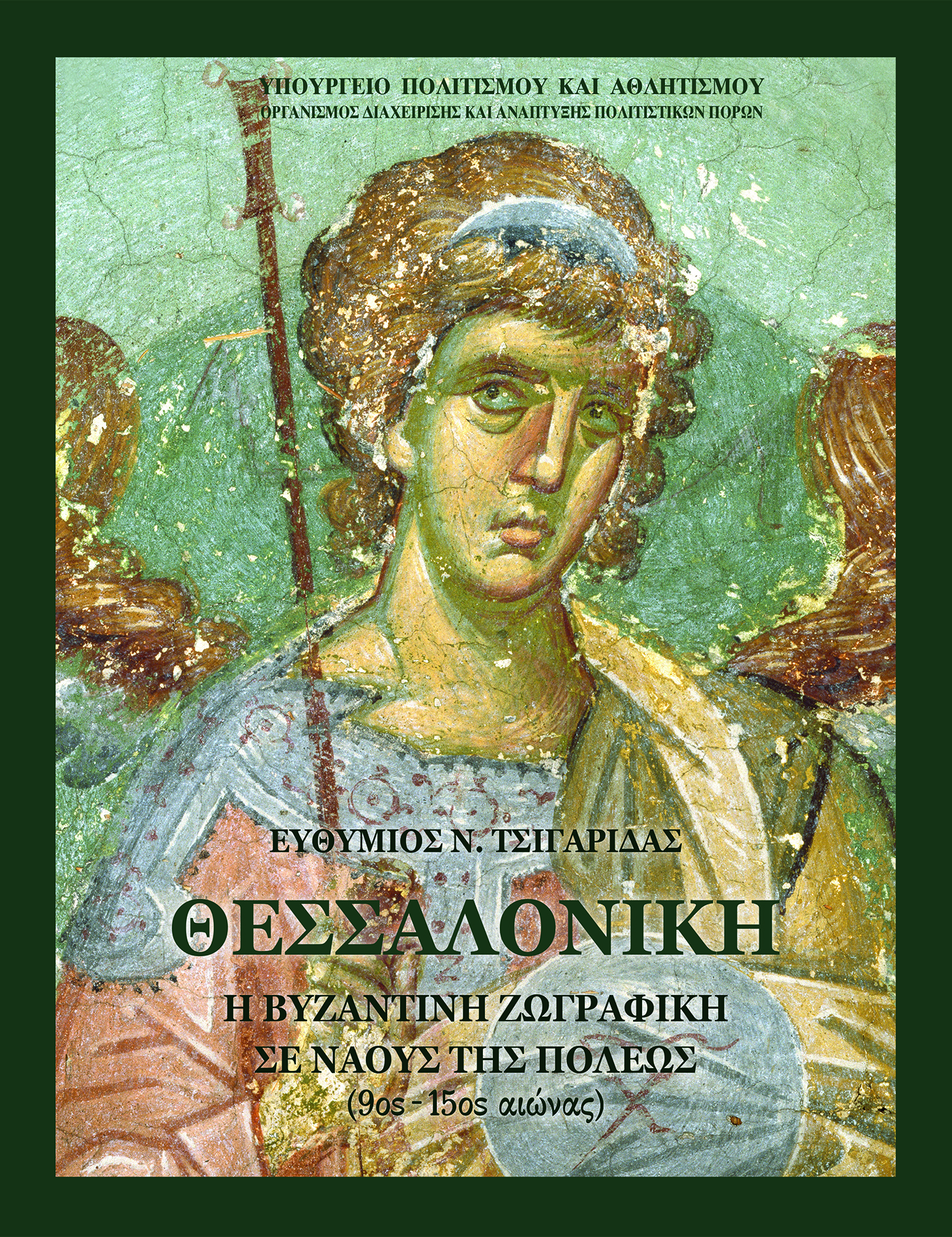

This panorama of the artistic flourishing in Byzantium is collected in the voluminous volume “Thessaloniki – Byzantine Painting in the Temples of the City (9th-15th Centuries)”, a publication of the Ministry of Culture (Organization for the Management and Development of Cultural Resources). ). The monograph, unique in Greek and international bibliography, is the life work of Euthymius N. Tsigaridas, the result of his many years of research work in the field of Byzantine and post-Byzantine art. The academic master, following the periods of time, appreciates painting in the brilliant church monuments of the periods of the Macedonian, Komnenos and Palaiologan dynasties – periods of prosperity, when the ideas of humanism and classical education had a great influence on art and science.

The development of wall painting, after the storm of iconoclasm and the triumph of Orthodoxy, in the temples erected where “Christ is described” and “God of heaven dwells”, was combined with the cultivation of Greek writing and a return to the norms of ancient art. , contributed to the “revival” of art during the Macedonian dynasty (867-1056). No monumental ensembles have survived from this period, only individual performances in three churches (Agia Sophia, Agios Georgios Rotontas, Agios Dimitrios).

Since the time of the Komnenos dynasty (1185-1204), frescoes have been preserved in a limited number in the churches of St. David, the Transfiguration of the Savior in the village of Gortiatis, as well as frescoes that adorned the funerary monument found in the church of Hagia Sophia. However, they do provide a general idea of art production in Thessaloniki in the second half of the 12th century, when few examples survive in Constantinople. Between the Latin occupation (1204–1224) and the re-establishment of the Byzantine Empire by Michael VIII Palaiologos (1263), the few surviving frescoes (“Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception” and “Saint Demetrius”) show that artistic activity may have been limited. but didn’t stop.

“Golden Age” of the era of Andronicus II Palaiologos

One of the glorious periods in the history of Thessaloniki, as “the city of poets and orators, the homeland and Helika of the Muses”, was the era of the Palaiologos. “The cultivation of humanistic studies in a fruitful combination with Orthodox theology and the spiritual ideal of the Eastern Church led to an artistic flourishing with radiance on Athos, in the region of Great Macedonia and in medieval Serbia. In particular, during the period of Andronicus II Palaiologos (1282-1328), which is rightly considered both from a philological and artistic point of view, the “golden age” of Thessaloniki, famous leading painters (Manuel Panselinos, Eutyches and Michael Astrapas, Georgios Kallergis and others. a.) and anonymous artists are engaged in the creation of portable images, illustration of handwritten codes, etc. At the same time, many churches were built and decorated with frescoes (and in one case with mosaics) in Thessaloniki, in Veria, in the Kastoria region, in Ahrid, in region of medieval Serbia, and in the saint they say that the decoration of old churches is being updated.

Nine churches save the frescoes of the “golden age”. In three (Agios Evfimy, Agioi Apostoli, Agios Nikolaos Orfanos) most of the original iconographic program has been preserved, in four (Taxiarches, Agios Panteleimon, Agia Aikaterini, the Catholicon of the Vlatadon Monastery) in a limited area, and in the churches of St. David and Panagia Chalkeon partial restoration of the original decor.

In his book, Professor Tsigaridas analyzes the pictorial compositions of each temple with historical and artistic elements and links them to the art of related monuments in the wider Greek region and in medieval Serbia. He is looking for artistic kinship with other wall ensembles, as well as the influence of ancient Greek standards. The pose, for example, of Christ at the Baptism of the monastery of Latomu clearly refers to Praxiteles Mercury (Roman sculpture, Pio-Clementino Museum, Rome).

The interest of the book lies in the detailed description of each type of representation, many of which are not visible due to their location (in domes, arches, at a high altitude from ground level) to temple visitors. The rich photographic material (550 photographs of Sotiris Heidemenos and the late Makis Skiadaresis and Yorgos Pupis) emphasizes the excellent technique, liveliness, beauty and expressiveness of what we call “Byzantine callus”, as the author notes. “We are talking about the humanization of Byzantine art, when the figures naturally express their emotions. This phenomenon, which has been observed since the end of the 12th century, reappears from time to time in Byzantine art and culminates in the monuments of the Palaiologan period, such as Protaton, Vatopedi, the Holy Apostles of Thessaloniki. According to Mr. Tsigaridas, the craftsmen working in Agia Apostoli come from Constantinople. “These are the same ones who worked in the Hora monastery. They used to talk about the “Thessalonica school”. My opinion is that the “school of Thessaloniki” does not exist. This is the “Constantinople school”, where artistic movements are formed, and from there they spread to a wider region. If there is any difference, it has to do with the personality of each artist.” The painting of the Church of the Holy Apostles of paleological architecture is indicative, where a brilliant set of mosaics and frescoes has been preserved, similar to that preserved in the monastery of Chora (Kariye Camii) in Constantinople. The similarities, for example, between Abel from the “Resurrection” of the Holy Apostles and Abel from the monastery of Chora are obvious. The reader can find this artistic relevance in the book. This is an excellent guide for both connoisseurs and visitors to the temples, which for centuries remained treasures of Byzantine art.

Source: Kathimerini

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.