Over the past three decades, the financial circumstances into which children are born have increasingly determined where they end up as adults. Growing up in a socio-economically unfavorable environment has an important and lasting impact on a person’s entire life. A new study based on data from a European survey of 27 countries examines how childhood socioeconomic disadvantage affects access to the labor market during adolescence and calculates the GDP equivalent cost of a childhood lived in poverty at the country level.

The main conclusions of the study are as follows:

- Growing up in a socioeconomically disadvantaged environment is associated with lower employment, lower income, and poorer health later in life. On average in European countries, working-age adults (25-59 years old) who lived in poverty as children are 3-6 percentage points less likely to be employed, and then, once integrated into work, earn about 20-21% less less than a year.

- Adults who experienced childhood adversity also have poorer health, equivalent to an average reduction of about two weeks per year in the time spent in good health.

- Collectively, the health and labor market costs associated with a disadvantaged childhood are high and costly. Labor costs alone average the equivalent of 1.6% of GDP each year, and health care costs the annual equivalent of 1.9% of GDP, creating average total costs equivalent to 3.4% of GDP per year. These estimates only cover results for working-age adults (25-59); if we had included an older population, this would likely have resulted in higher estimated costs.

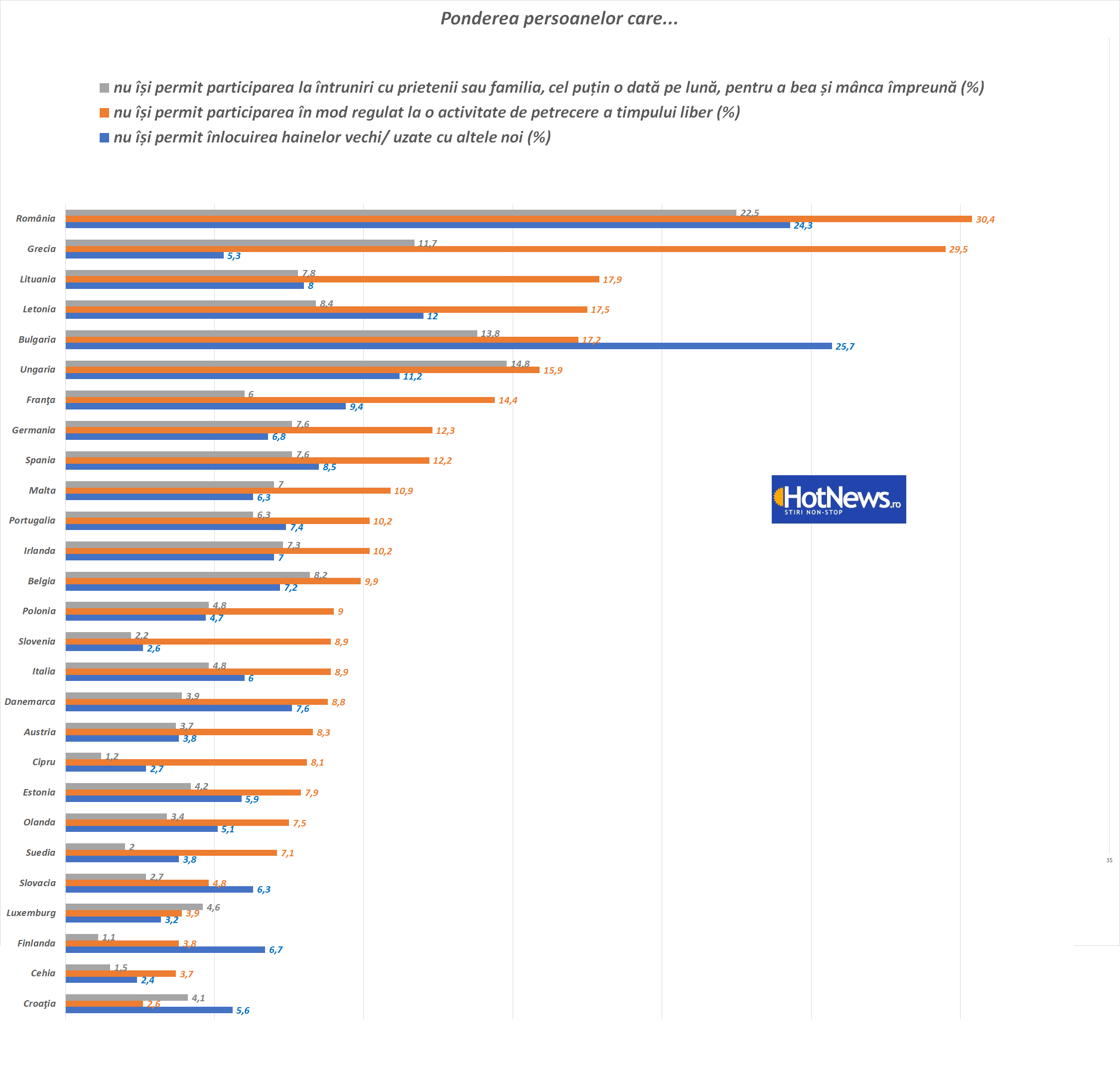

The share of those who do not have school supplies around the age of 14 ranges from less than 1% in Finland to 56% in Romania

If we look at material deprivation, the proportion of respondents aged around 14 who say they do not have the opportunity to eat meat per day ranges from 3% in Denmark and Sweden to 30% in Hungary.

Similarly, the proportion of those who say they do not have the things they need for school under the age of 14 varies from less than 1% in Finland and Sweden to 11% in Greece. This is an average, because if we take into account those with the lowest incomes (the first income quintile), these figures range from 12% in Denmark to 93% in Hungary and from 4% in Sweden to 56% in Romania.

The proportion of respondents with one parent in the top income quintile who say they cannot afford to go on holiday for at least 7 days (those aged 14 and over) varies significantly between countries, with rates varying for those with the lowest income from 61% in Finland to 99% in Greece, Portugal, Spain and Hungary and 100% in Romania.

Education plays the most important role: on average, in the 24 countries analyzed, low education leads to a 4 percentage point drop in annual labor income for men in the highest income quintile and a 5 percentage point drop for women in the same quintile. .

The results show high costs for each country, on average equivalent to 3.4% of annual GDP.

Children from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds often fall behind academically, for example, score lower on tests of cognitive skills in early childhood and often leave school before their peers

Children from disadvantaged families are also more likely to have poor physical and mental health, more likely to develop emotional and behavioral difficulties and significantly less satisfied with life

The literature on intergenerational mobility has long illustrated how the social and economic outcomes of adults are closely related to the socioeconomic status of their parents over time.

Social mobility means a change in the socio-economic situation of a person in relation to parents (intergenerational mobility) or during life (intergenerational mobility).

Social mobility is related to equality of opportunity: the extent to which people have the same chance to succeed in life, regardless of parents’ socio-economic background, gender, age, sexual orientation, race, ethnic origin, place of birth, etc. circumstances beyond their control.

Social mobility and equality of opportunity can be measured by earnings, income or social class, but can also be understood as encompassing other dimensions of well-being such as health and education.

According to several studies, this parental “transmission of disadvantage” operates through various channels with cascading effects that affect many areas of life.

Source: Hot News

Lori Barajas is an accomplished journalist, known for her insightful and thought-provoking writing on economy. She currently works as a writer at 247 news reel. With a passion for understanding the economy, Lori’s writing delves deep into the financial issues that matter most, providing readers with a unique perspective on current events.