The crises of recent years have also affected the school population of the region. In addition, in Romania, legislative changes have led to changes in the mandatory length of schooling, according to an analysis by Alpha Bank sent to HotNews.ro on Monday.

After 2019, the duration of compulsory education was gradually increased from 11 to 14 years (by amending the Law on National Education No. 1/2011). Thus, by 2020, in addition to the already mandatory 11 years of education, a large group from kindergarten and grades XI and XII, a total of 14 years of education, became mandatory. And by 2023, the middle group from kindergarten has also become mandatory for the general 15-year education.

By 2030, it will also be compulsory for small groups from kindergarten to general 16-year-old education.

Romania has a younger population than the countries of the region, the share of the school-age population (up to 24 years) in the total population is the highest and stable compared to the countries of the region (Fig. 1).

In 2022, the average age of the population was 41.9 years, the same as in Poland (41.8 years), but lower than in Hungary (42.4 years), the Czech Republic (42.3 years) or Germany (44.3 years) . A high proportion of the school-age population theoretically guarantees the improvement of human capital in the future, provided that young people are involved in the education system. But in Romania, the number of schoolchildren compared to the total population is the smallest in the region and is decreasing.

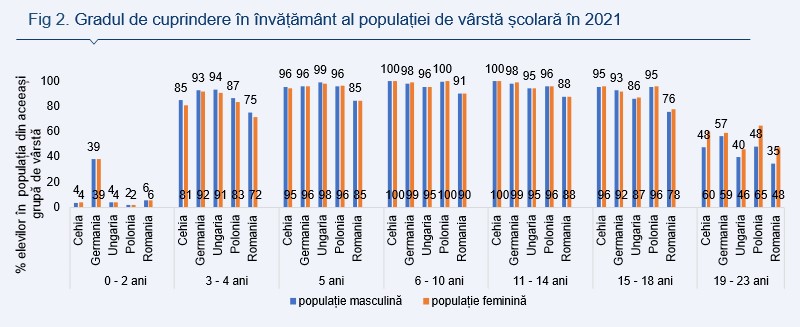

In 2021, despite the mandatory nature of pre-university education, the level of educational inclusion of the school-age population is lower compared to the countries of the region for all age groups of both the female and male population and decreases with increasing age (Fig. 2).

In the 6-10 age group, which largely corresponds to primary education, 91% of boys and 90% of girls were enrolled in school compared to 100% in the Czech Republic and Poland, or 98%/99% in Germany and 96%/95% in Hungary. In the 11-14 age group, which mostly corresponds to secondary education, 88% of boys and girls were enrolled in school, compared to 100% in the Czech Republic, 98%/99% in Germany, 96% in Poland and 95% in Hungary. . In the 15-18 age group, which mostly corresponds to secondary school education, 76% of boys and 78% of girls attended an educational institution, compared with 95%/96% in the Czech Republic and Poland, 93%/92% in Germany and 86%/87 % in Hungary.

Low participation in pre-university education means low participation in higher education and reduced potential for human capital accumulation. Among the 19-23 age group, only 35% of men and 48% of women had attended an educational institution, compared to 57%/59% in Germany (the country with the highest tertiary enrollment among the countries analyzed) or 40%/46% in Hungary (with the lowest inclusion in higher education).

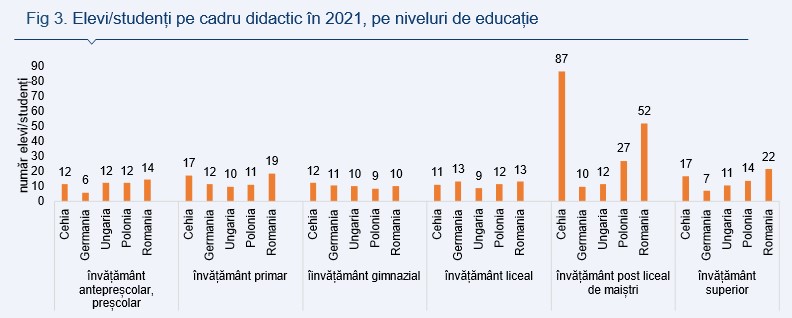

The teaching staff in relation to the school population is lower than in the countries of the region at all levels of education except secondary school. There were 51 students in higher education, 22 in higher education, 19 students in primary education, 14 students in preschool and preschool education, 13 students in high school and 10 students in secondary education per teacher (Fig. 3).

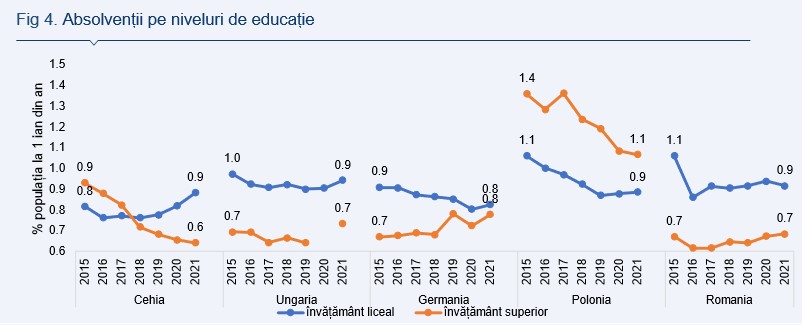

The number of high school graduates (0.9% of the population in 2021) is higher than university graduates (0.7% of the population in 2021), as in the Czech Republic and Hungary (Figure 4). In Poland, the opposite is true, and in Germany, both categories of graduates tend to equalize. Romania is the regional leader in the share of higher education graduates in three fields: business, administration and law, information and communication technologies, as well as agriculture, forestry, fisheries and veterinary medicine (Figure 5).

Graduates in these fields account for 26.9%, 6.9%, and 4% of the total number of higher education graduates, respectively. Conversely, the share of graduates in the field of educational sciences (5.8%) is half of the share of other countries.

Although the length of compulsory education has increased, enrollment is low and declining, reducing the potential for human capital accumulation and excluding most of those who remain out of school from a decent life. As the teaching profession does not seem to attract young people, the shortage of teaching staff risks deepening and further worsening the degree of inclusion in education.

Source: Hot News

Lori Barajas is an accomplished journalist, known for her insightful and thought-provoking writing on economy. She currently works as a writer at 247 news reel. With a passion for understanding the economy, Lori’s writing delves deep into the financial issues that matter most, providing readers with a unique perspective on current events.