Hundreds of foods have been pulled from store shelves in recent years because they were deemed unsafe by the National Veterinary and Food Safety Authority (ANSVSA), the body responsible for overseeing food safety, hygiene and quality.

According to data published by ANSVSA and consulted by HotNews.ro, there were an average of 42 food seizures per year. The fewest withdrawals were recorded in 2017.

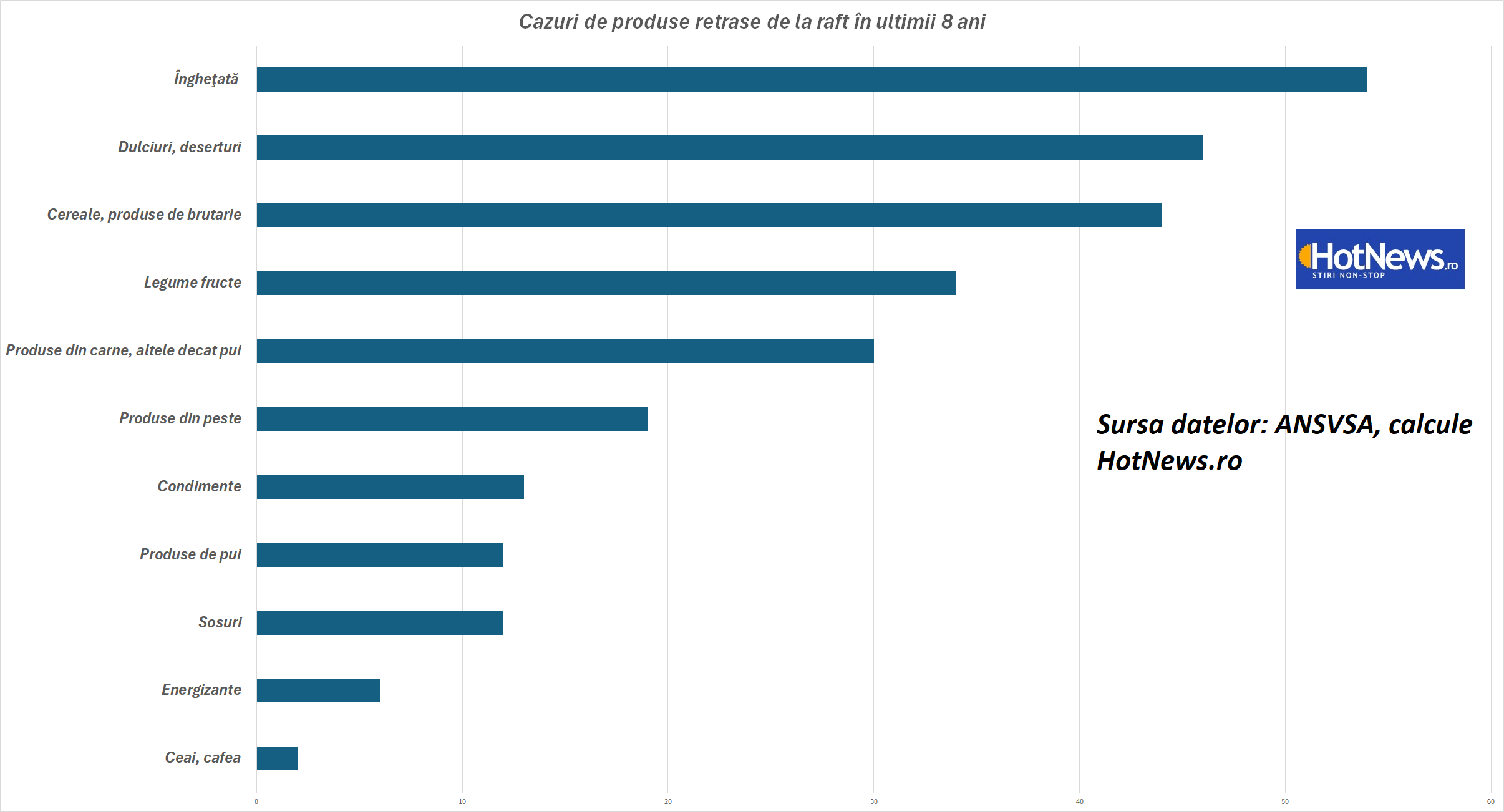

Ice cream, sweets and cereal dominate withdrawal charts

Consuming these products can lead to a severe type of poisoning that particularly affects pregnant women, people over 65 and people with weakened immune systems. shows research on this topicrecently published.

The recalled food products mainly come from Turkey, China and Latin America. A small part comes from the European region

The presence of foreign bodies (pieces of wire, glass, stones) is sporadically reported in recalled batches of food products.

In terms of origin, the recalled/removed food batches mainly originate from Turkey, China and Latin America, with only a small proportion originating from the European region.

Approximately 5% of seized food products are declared as domestic, but without information about the raw materials used, the authors of the cited study also show.

A simple declaration of processing in Romanian companies does not ensure the safety of the supply of raw materials from Romania.

This information is consistent with other findings in the literature, which emphasize the prevalence of foreign capital in food retail chains and the tendency for foreign direct investment to be concentrated in agricultural production or large enterprises of primary processing of agricultural raw materials.

Recall of products from major retail chains – more than 85% of the total number. The highest figures are at Carrefour, Mega Image and Auchan

The majority of recalls/recalls were sent by retailers, with over 85% of product recalls in large chain stores.

In absolute terms, Carrefour, Mega Image and Auchan recorded the highest rates of product recall actions.

CONCLUSIONS

The joint efforts of regulatory bodies such as ANSVSA, the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development confirm that it is not uncommon for non-compliant products to reach store shelves, but fortunately are identified and removed in time.

In these efforts, the essential role of the authorities in coordinating seizures and ensuring compliance with the rules is evident.

The reasons for withdrawal vary from the presence of allergens and contamination with microtoxins to various chemical or biological contaminants. The nature of the supply chains is highlighted by the diverse origins of the recalled products, with notable shares from Turkey, China and Latin America.

See the full study here

A brief history of nutrition

Today we can afford to buy any exquisite food or food brought from here for tens of thousands of kilometers. But it was not always like that.

Starting from about 1270, the economic development of Europe became practically zero. Agrarian expansion slowed down, and the area for cultivation decreased. The situation was becoming more dramatic than ever. In the last decades of the 13th century, agricultural production steadily declined and a series of very severe periods of famine began, recalls Massimo Montanari in “Famine and Plenty. The history of food in Europe”.

In difficult times, the tension between the townspeople and the peasants intensified. The former, privileged in normal times, were even more protected in times of crisis, especially if the city was rich and powerful. Therefore, during periods of famine, hungry peasants ran out into the streets of the city in the hope of finding something to eat.

Repeated periods of food stress caused a state of widespread malnutrition and physiological weakness, setting the stage for the plague epidemic that ravaged the continent between 1347 and 1351. Overall, the plague seems to have wiped out at least a quarter of the European population.

After the tragedy of the plague, it was believed that due to the lack of people, the fruits of the earth can be found in abundance. However, the prediction did not come true. However, the situation actually improved, and it could not be otherwise, after such a disaster.

Meat consumption has been attested for a long time, but perhaps in the second half of the 14th century, this consumption increased in general, even for the lower classes of society. This is the period of “predatory” Europe (Braudel). In Germany, people of the 15th century consumed an average of 100 kg of meat per year per capita. In the Mediterranean regions, the dietary role of meat was not so decisive; here too, however, documentation from the 14th to 16th centuries emphasizes negligible levels of consumption.

Leaving the walls of cities, the situation changes, but not radically, because meat on the tables of peasants in the 14th and 15th centuries was not at all rare, as it was not even in previous centuries. However, the contrast between the city and the countryside remains a fundamental element of the social distribution of food for a long time.

The church norm demanded abstinence from meat for about 140-160 days a year. This restraint has become the central leitmotif of moral treatises and the norm of repentance since the first centuries of Christianity. Hence the need for alternative food products: vegetables, cheese, eggs and, no less important, fish as an excellent substitute for meat.

Between the 14th and 16th centuries, the ideology of the ruling classes imposes its own way of life on various social groups: the ways of eating, dressing and living are carefully codified. Examples in this sense are the so-called “laws of luxury” aimed at controlling certain behavior and consumption.

The relationship between nutrition and social status was initially purely quantitative in nature. However, over time, the qualitative dimension was increasingly formed, giving rise to the “court” ideology of food in the 12th and 13th centuries: one should eat according to the “quality of a person”.

Faced with a virtually different reality, with unknown plants and animals, with unusual food, European explorers and conquistadors show both disbelief and curiosity. From the time the new foods became known to Europeans, it took a long time before they became important in their food system. This delay would seem to indicate a long and significant lack of interest in European food culture for new American contributions.

New products were accepted only when and to the extent that they were absolutely necessary. We can talk about the double penetration of new food products into Europe. The first occurred in the 16th century, immediately after the conquering expeditions, and, like the second, caused a famine. The increased need for food requires the search for possible solutions to the problem in new products. It is rice in some regions, corn or potatoes in others.

By the middle of the 16th century, meat consumption by Europeans began to decline. At the same time, the quality of bread also decreases. At least in the 17th century, European townspeople were used to eating wheat bread. Now other grains are beginning to gain momentum. The “Bread Hierarchy” reflects the social hierarchy: white bread is reserved for the richest, “light” (but not quite white) bread is for the middle class, and black bread is reserved for the poorest.

With the deterioration of the food situation and the immediate threat of starvation, manifestations of anger and intolerance take on more acute and violent forms. This is an era of great conflicts over food, connected not only with production deficiencies, but also with the development of capitalism. The number of poor has increased tremendously, and the food privileges of the cities are in danger of being destroyed. The poor begin to be imprisoned together with the insane and criminals.

About the fact that drinking and eating a lot, some said that it is bad (and that it is bad), others claimed that this is how a man’s dignity is revealed. The difference in nutrition between the regions of Europe is documented. The gulf between different dietary cultures deepened in the 16th century, when the Protestant Reformation rejected, among many other things, the dietary norms of the Romanian church. And then – no fasting, no abstinence.

Source: Hot News

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.