Next month, Sotheby’s in New York will auction what could be the most expensive book of all time: a Bible that some experts estimate is worth $50 million, The Conversation reports.

It is said to be one of the oldest copies of the Bible in the world, a book like no other. But what exactly is it about?

The Bible is the best-selling book in history, according to Guinness World Records as far back as 1995, with over 5 billion copies sold and distributed. It’s true that it also had a significant advantage: when Johann Gutenberg built his famous printing press in the 15th century, the Bible was naturally the book of choice for mass distribution.

At that time, Gutenberg printed a Latin version of the Bible known as the Vulgate, translated from Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek by St. Jerome in the late 5th century AD.

About the origin of the Bible

We owe this linguistic diversity to the fact that the Bible is not really a book, but a collection of books written at different times by different authors who did not all speak the same language. The very word “bible” means “books” in the plural (Greek “ta biblia”).

The Bible, which will be auctioned on May 16, is written in Hebrew and dates from around the 10th century AD. This is a respectable age, but much older manuscripts exist.

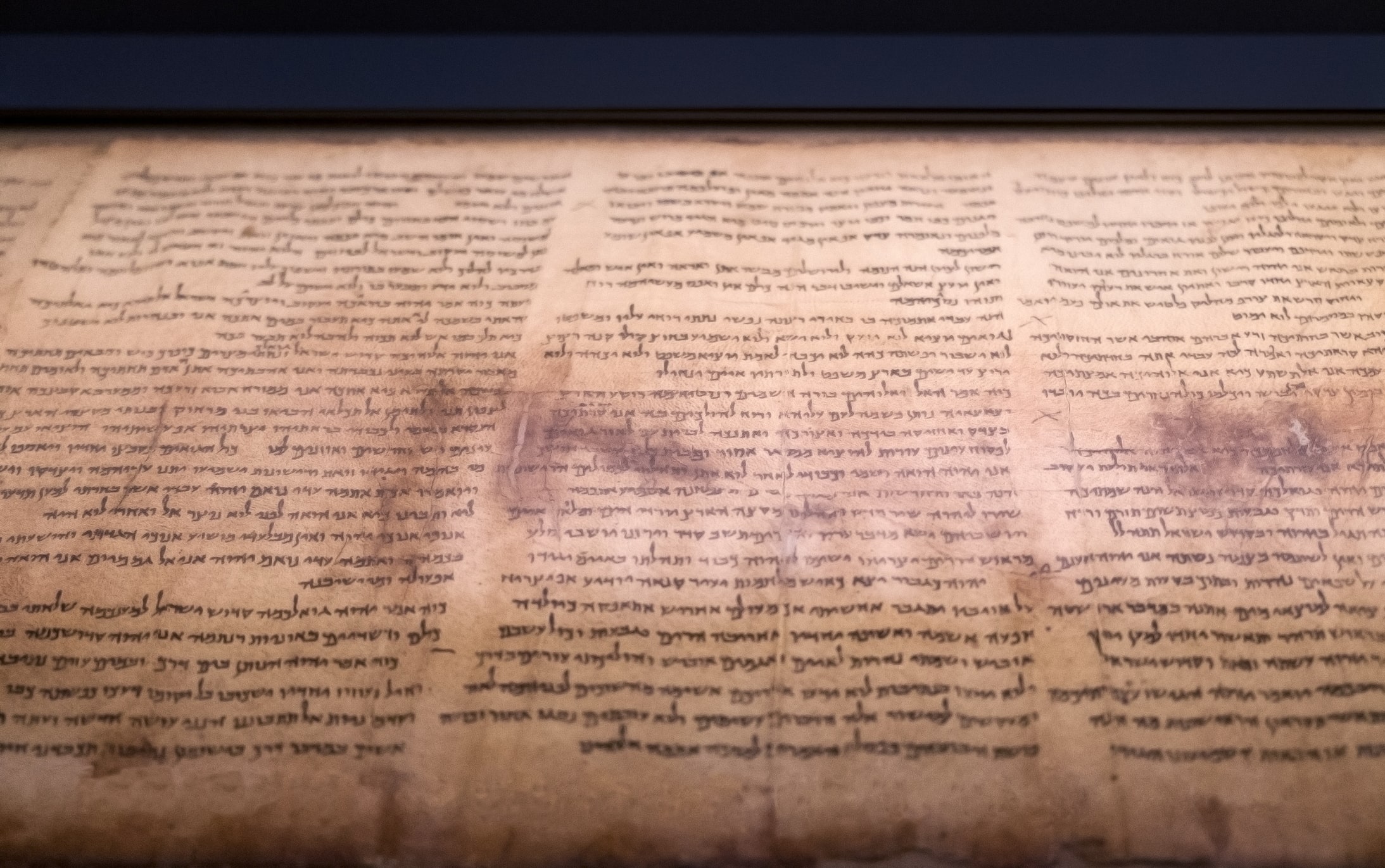

A thousand years ago, scribes copied the same books on parchment or, more rarely, on papyrus. Part of these manuscripts remained hidden in caves on the western shore of the Dead Sea for more than two millennia, and were discovered only in the middle of the 20th century by Bedouins.

These “Dead Sea Scrolls”, as they came to be called, are the oldest known Bible manuscripts. Unfortunately, they are fragmented, with more than 30,000 pieces that need to be pieced together to form about 1,000 manuscripts.

There are at least that many puzzles to solve without a pattern and with most pieces missing. The oldest date back to the 3rd century BC, but some researchers suggest that they may even be two or three centuries older than that.

The most recent were dated to the second century AD. In most cases, the dating method was based on palaeography – the way letters were written – starting with the assumption that people did not write in the 3rd century BC. just like in the 2nd century AD.

Fragment of manuscripts found at the Dead Sea (PHOTO: Menahem Kahana / AFP / Profimedia Images)

The problem with the dating of ancient manuscripts

Carbon-14 dating, perhaps the best known to the general public, is useful in theory, but it presents several problems: it is a destructive method because it requires cutting samples from manuscripts, samples that are then ground up and, indirectly, destroyed.

In addition, they are often contaminated, which leads to abnormal results. And even if they are correct, the results need to be calibrated, which sometimes leads to more possible and quite inaccurate data.

Finally, even if the resulting date is plausible, the use of carbon-14 dates only the papyrus or parchment, not the inscriptions on it. It is possible that the text itself was applied to the manuscript much later, especially if the parchment was washed and then reused, which was common in the ancient world.

Returning to the copy of the Bible that will be auctioned, it has been carbon-14 dated, but the results have not been published. We are told that this Bible dates from the late 9th century AD. or early 10th century, without providing Sotheby’s with further details.

It is clearly in the seller’s interest to offer as early a date as possible to increase the value of the bids received, to the point of presenting this Bible as the “missing link” to the Dead Sea Scrolls.

However, they are actually separated by millennia, so a difference of a few decades in the dating of the Bible in question would not be significant.

Qumran Caves, where the Dead Sea Scrolls were found (PHOTO: Suzanne Held / akg-images / Profimedia)

A “missing link” in the history of early Christianity?

However, such a connection exists: Greek Bibles dated to the IV-V centuries of our era. The most famous of them is located in the Vatican, hence its name “Codex Vaticanus”.

As for the books of the Bible written in Greek, these manuscripts preserve the text in the original language. However, books written in Hebrew and Aramaic must be translated into Greek. And to translate is to betray.

This raises doubts about the accuracy of the Greek version, especially if it differs from a later Hebrew Bible, as is the case with the one up for auction.

What if the Greek translators were somehow incompetent or careless? The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls has clarified such questions, since some of these manuscripts, including the Hebrew ones, present the same version of the text as in the Greek Bible.

In other words, the Greek translators did a pretty good job, especially since the Hebrew text before them was different from what would later be seen in the Hebrew Bibles of the Middle Ages, when the biblical text underwent a metamorphosis.

Over the centuries, different versions of the Bible passed from one hand to another, repeatedly copied by Jewish or Christian scribes who did not necessarily communicate with each other. In the early Middle Ages, Jewish scribes developed a system of punctuation for the biblical text. It should be said here that the Hebrew alphabet does not mark vowels systematically and precisely.

In fact, the same text can often be read in different ways, which can have serious consequences for those who believe the Bible is the exact word of God and advocate a literal interpretation.

To remove any ambiguity, small dots and lines are added to emphasize accurate vowel pronunciation, punctuation, and cantillation (psalmodification of the melodic line). Interestingly, several different pronunciations competed with each other until the 10th century, when the first Bible appeared with the Hebrew pronunciation that is still used today.

This Bible is the “Aleppo Codex” dating from about 930 AD. It is exhibited in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. A few pages are missing, but its “offspring,” the Leningrad Codex, copied in AD 1009, is complete. This is a manuscript that serves as a reference for studying the Hebrew Bible.

Pages from the “Aleppo Codex” (PHOTO: © Rumata7 | dreamstime.com)

The Bible as a living text

However, the copy of the Bible that will be auctioned in New York is neither the “Leningrad Codex” nor the “Aleppo Codex”, but a different version, the “Sassoon Codex 1053”.

Unlike the Leningrad Codex, this one is missing pages, so it can’t claim to be the oldest complete Hebrew Bible in the world, despite what Sotheby’s says on the auction house’s website (or even on Wikipedia, which links to -Sotheby’s website for this information). ).

Its punctuation also differs slightly from the Aleppo Codex, which can be seen either as a flaw or as a quality:

Believers who wish to read the Hebrew Bible according to the official pronunciation will ignore this codex, while scholars rejoice in the value of the manuscript for the comparative study of Hebrew punctuation.

The astronomical value of 30-50 million dollars, estimated at “Codex Sassoon 1053”, once again shows the relevance of the Bible to billions of believers around the world, but also depends on certain features of this manuscript.

For example, the books of the Hebrew Bible are arranged in a slightly different order compared to the one we know, the book of the prophet Isaiah is placed after the book of Ezekiel, and not before the book of Jeremiah.

Imagine watching the Star Wars movies in a different order than they were released in theaters. The effect would be different.

This is what happens in the Codex of Sassoon: the Bible is read differently. Each manuscript is unique in its own way, and the millennia-long history of the Bible encourages us to discover it as a living text, and not as a block of granite that lends itself to subtle reading.

Source: Hot News

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.