Growing up in Canada, John Wagner was met with incredulous looks whenever he mentioned his origins. He spoke Greek, his parents were Greek immigrants, but his surname repelled some of the interlocutors. Until he decided to dig into the past. In compiling his family tree, he also had to deal with a difficult aspect of his family history. During the years of the occupation, his relatives, descendants of the Ottonian Bavarians, were expelled from Attica as part of the Nazi propaganda campaign. The initiator of this operation, which was aimed at repatriating the “lost Germans” in order to preserve the imaginary purity of blood, apparently, was Himmler himself.

“I felt the need to learn more about the past, to approach history in search of evidence, and not rely only on oral evidence,” says Mr. Wagner “K”. “I understand that I can take risks, digging deeper, if the investigation reveals unpleasant aspects. But I want to understand what happened, to understand the intentions, how someone thinks when they make such a decisive decision.”

The extended family of his father, Richard Wagner, immigrated from Germany to Canada in two parts, in 1953 and 1956. John Wagner was born in Montreal, in a home where the Greek language was dominant. He studied molecular biology and currently works for a laboratory supply company. Until 1942, his grandparents lived with their nine children in Attica, in Old Heraklion. In 1837, a military colony of Bavarian mercenaries and artisans was built here, who followed Otto as king of Greece. After the expulsion of Otho in 1862, some remained and became Hellenized over the years. The German language died out or was completely forgotten in some families, and only the surname now reminded them of their origin.

To learn more about what happened during the occupation years and to understand the context of his relatives’ flight from Greece, Mr. Wagner enlisted the help of Franco-German historian Valentin Schneider last month. In recent years, Schneider has attempted to record in great detail the German military and paramilitary forces that were intermittently or for extended periods in Greece, from the time of the invasion to their withdrawal. He lives in Athens and often travels to Germany to search for information in the German historical archives. There, studying materials on microfilm, he found dozens of pages related to Old Heraklion and the resettlement project for the “lost Germans”.

As Mr. Snyder explains to K, similar population transfers – but on a larger scale – were part of the strategy pursued by Nazi forces in other countries at the time. They tried to gather communities with Germanic roots from distant places such as Bessarabia (most of which corresponds to modern Moldavia) and transfer them to the conquered areas of Eastern Europe, in which they created the so-called “living space”. The ultimate goal was to replace the local population with German settlers.

“They wanted to avoid the ‘dissolution’ of German blood,” says Mr. Schneider, who finds it paradoxical that something similar happened in the small community of Old Heraklion with a few hundred inhabitants. “This is a racist practice. They take people who have lived in Greece for three or four generations, they are Greek citizens, they speak Greek, they do not belong to any marginal community. But since they have German blood, they are going to strengthen the German race,” he points out.

It seems, although it is not entirely clear from the sources so far available, that the application of the program to the descendants of the Bavarians in Greece is connected with the visit of the head of the SS, Heinrich Himmler, to Athens in May 1941.

On the second floor of the Wagner house in Old Heraklion, there was a German school where Martha Schumann taught. Her name first appears in Athens before the war. “We know little about her exact role, perhaps she was on Himmler’s direct mission and collaborated with the Athens branch of the Nazi Party’s foreign organization under the direction of the classical archaeologist Walter Brede, also director since 1937 of the German Archaeological Institute.” , notes Mr. Snyder.

She seems to have taken over the dissemination of propaganda as well. According to reports Mr. Schneider found in archival records, Schumann told the families that if they returned to Germany, they would spend two weeks in the barracks and then receive their land. He promised that they would be offered new clothes, that life in Germany was cheaper. However, the reality turned out to be different.

It seems that the order for the operation to “repatriate” the Hellenized Bavarians was given by Himmler himself.

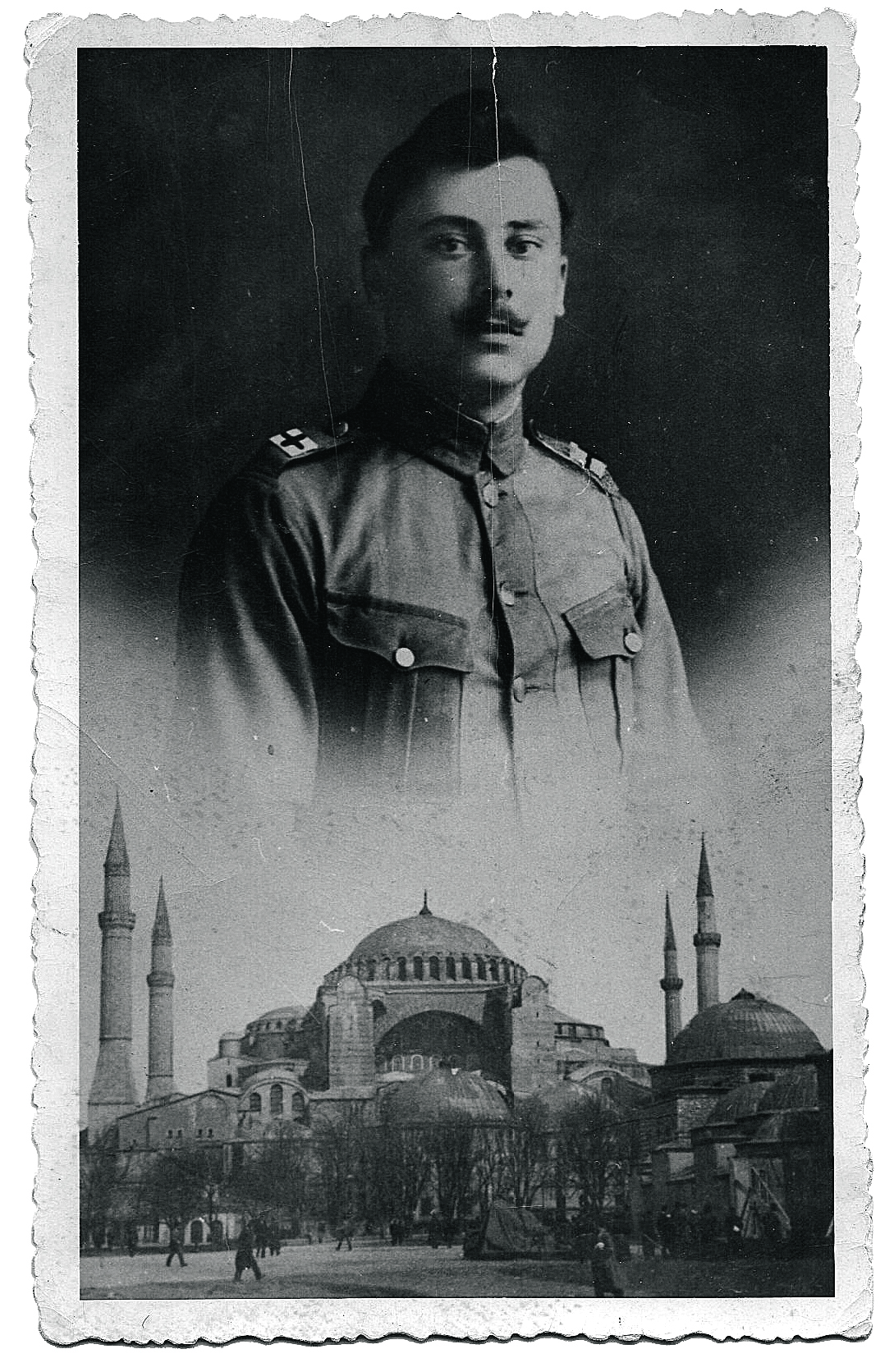

John Wagner recalls that his grandfather, Alois, participated with Greece in the Asia Minor campaign. He still keeps his photographs in the military uniform of those years. As he says, according to the family narrative, the decision of his relatives to leave Old Heraklion for Germany was mainly due to conditions in occupied Athens. “My grandfather’s main concern was to avoid the great famine. He had nine children, he made a decision about them,” he says.

In the material found by Mr. Schneider in the German archives, there is a detailed analysis of Old Heraklion by the SS. They describe how the inhabitants live, their occupations and incomes, how many vineyards and olive groves they have, and what each field produces, even how much it costs to buy a shirt.

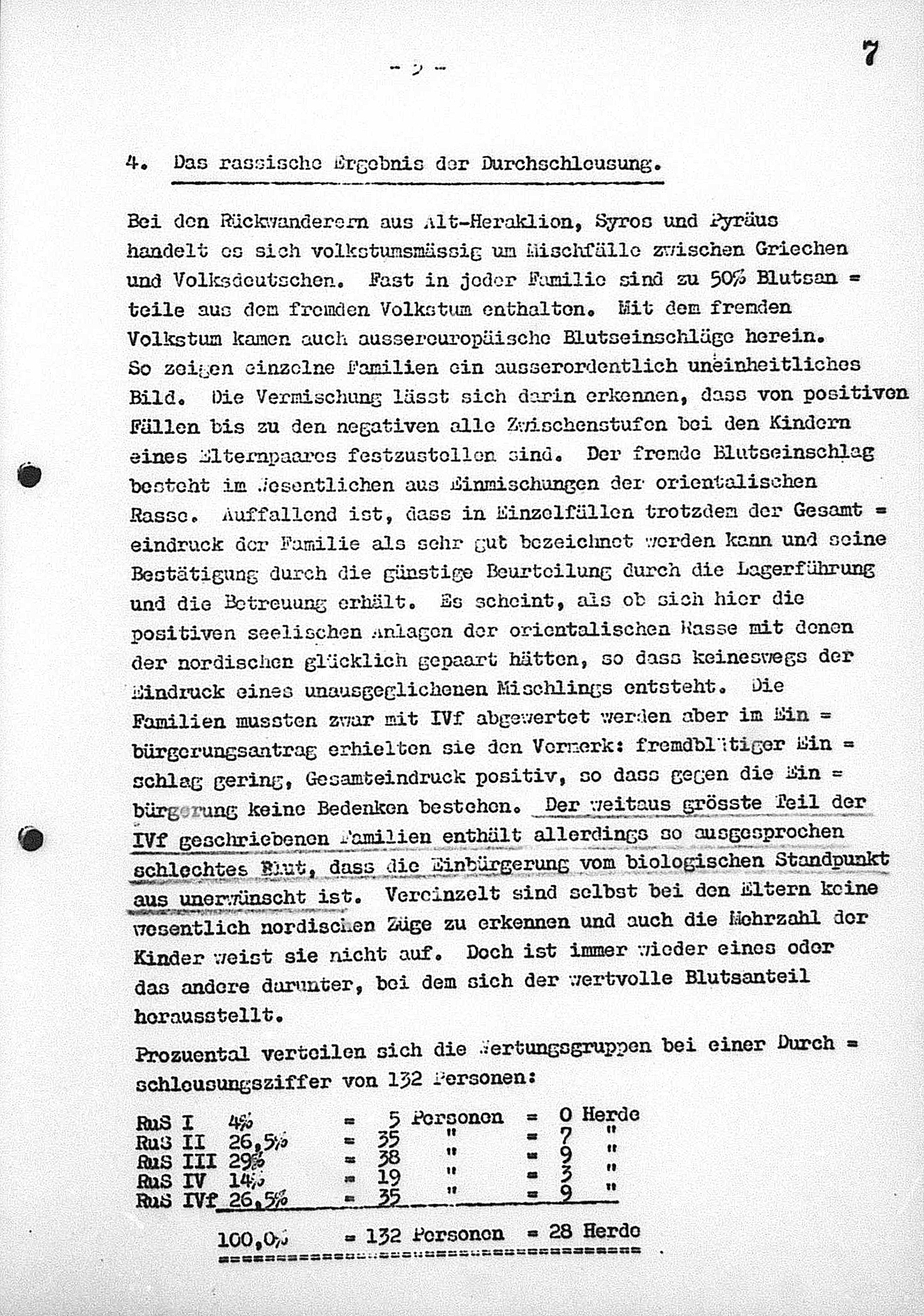

Data given by members of the SS in another report, before leaving for Germany, about 150 people refer to the biological analysis of “human material”. They note in their documents the state of health of the resettled residents, observe whether their teeth are strong, whether they are ill with malaria or tuberculosis. They fix impurities and notice that in some families the amount of “waste” blood is so large that they are unlikely to be naturalized as Germans. In fact, they classify them into certain racial categories according to their family history.

The resettlement (Umsiedlung) of the Germans from P. Heraklion took place on the orders of Himmler in 1942 and with the consent of the Italian authorities, who had political and military sovereignty in Athens during the first years of the occupation. Some did not follow the same path and remained in Greece. Mr. Snyder notes that in 1943 a second operation was carried out to resettle 100 people of German origin from Athens and possibly also from Piraeus.

The resettlement of families from Old Heraklion took place by train. Women and children were traveling in cars, and men along with the goods. They arrived in Passau, Bavaria, where the German authorities placed them in a camp to confirm the degree of racial Germanism of each. The Nazi newspaper Donauzeitung, in an article about German soldiers in the Balkans, calls their resettlement “the return from the adventures” of the century. The motives of each of the migrants are unclear: whether they were convinced by what Schumann ordered, whether they felt they had no alternative and tried to break out of poverty, or whether some of them joined Nazism.

However, it does not seem that all of them were warmly welcomed in Germany. Mr. Wagner says his relatives learned German but were treated mostly as refugees from a distant land and were not given the promised property. “I think they saw the move as an opportunity for a better life,” he says. His grandfather and two of his uncles, who were quite old, were conscripted to German soil. He does not yet know many details about this issue, which he calls the source of shame.

His father was 13 when they left Athens. As a child, he worked for a time as a miner in Belgium until the family immigrated to Canada. They could not return to Greece.

Mr. Schneider started his research in German archives in 2019. The project he is carrying out on the “database of German military and paramilitary forces in Greece, 1941-1944/45” is carried out by the Institute for Historical Research of the National Research Center. Foundation and funded by the German Federal Foreign Office through the Hellenic-German Fund for the Future.

So far, others have turned to him for answers. In one case, Albrecht Schroeter, a German mayor for years with the Social Democrats in Jena who opposed neo-Nazism, tried with the help of a historian to establish whether his grandfather had been involved in war crimes in occupied Crete. Mr. Snyder was also approached for help by a Greek teacher who was looking for more information about the day when German troops almost completely set fire to the houses in Doxa Gortynia.

Searches in the past can provide explanations or confront unpleasant information. For Mr. Wagner, this is an important process. Perhaps decades have passed, he himself is not involved in this sequence of events, but each new tile added will help him better understand the choices and decisions of his ancestors.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.