From 7 am, and often earlier, the Tel Aviv beach begins to come to life. Even on this early morning, the beach volleyball courts are packed, with men and women jogging and others just going to work. The embankment is perhaps the busiest part of the city, and this is no coincidence. His 2018 design by MKR (Mayslits-Kassif-Roytman) Architects won international awards for not only breaking down the wall between sea and city, but something even more important: creating a new urban culture.

The founders of the office are Udi Kassif and his wife Ganit Meislitz (later Maor Roitman joined the team), architects with many important projects in Israel, but also often in contact with Greece, especially Athens. Our discussion begins with the coastal cities of the Mediterranean. “Even 50 years ago, the sea was the garbage can of mankind,” he says. “Drainages ended at the coastal zone, there were high-traffic roads, heavy industry such as oil refineries – we recently unfortunately saw one at Agia Theodorou in Corinth – and all sorts of unwanted uses. Only in the last few decades have we realized their potential for recreation, that is, as part of the daily life of the inhabitants, and tourism. And then gradually their pollution stopped and large hotels began to be built. This is what happened in Tel Aviv. There is a photograph from the beginning of the last century, in which people in suits are sitting on the shore with their backs to the sea. That was the prevailing opinion.”

The first embankment was created in the Tel Aviv beach area in the 1930s. However, the first major renovation took place many years later, in the 1980s. “It was planned to build a large sewer pipeline along the coast. Therefore, the architects of that time thought that, on the occasion of the projects, they could build a coastal promenade similar to the Copa Cabana in Brazil. They built a beautiful path of synthetic stone and beautiful patterns, including six cafes by the sea. At the same time, they installed breakwaters, which helped reduce the speed of the sea and more than double the length of the beach. This two-kilometer walk became the image of Tel Aviv in all advertising campaigns of that time. It was something unique to Israel. Around the same time, the first large hotels began to be built. This reconstruction for the first time brought into the life of the city the coastal zone of Tel Aviv, which until then had been concentrated in the center, in the inner part.

However, in the northern part of the coast there was a section closed to pedestrians: the port. “It was created in the mid-1930s because of the unrest that existed in Jaffa between Jews and Palestinians. But it was a terrible port that never really worked and was finally closed in 1963. Gradually, the area fell into disrepair, turning into a center for prostitution and infamous bars. In 2003, the port administration announced a tender for the improvement of the territory of the port, which we won. The space opened in 2008 and was a great success, it was a real revolution for the “street” life of Tel Aviv. Suddenly, a public space was created that was not a park where you could walk, take your children to play, eat, have a good time. Characteristically, until recently it had more visitors – about 3 million a year – than the Wailing Wall, Israel’s holiest site.”

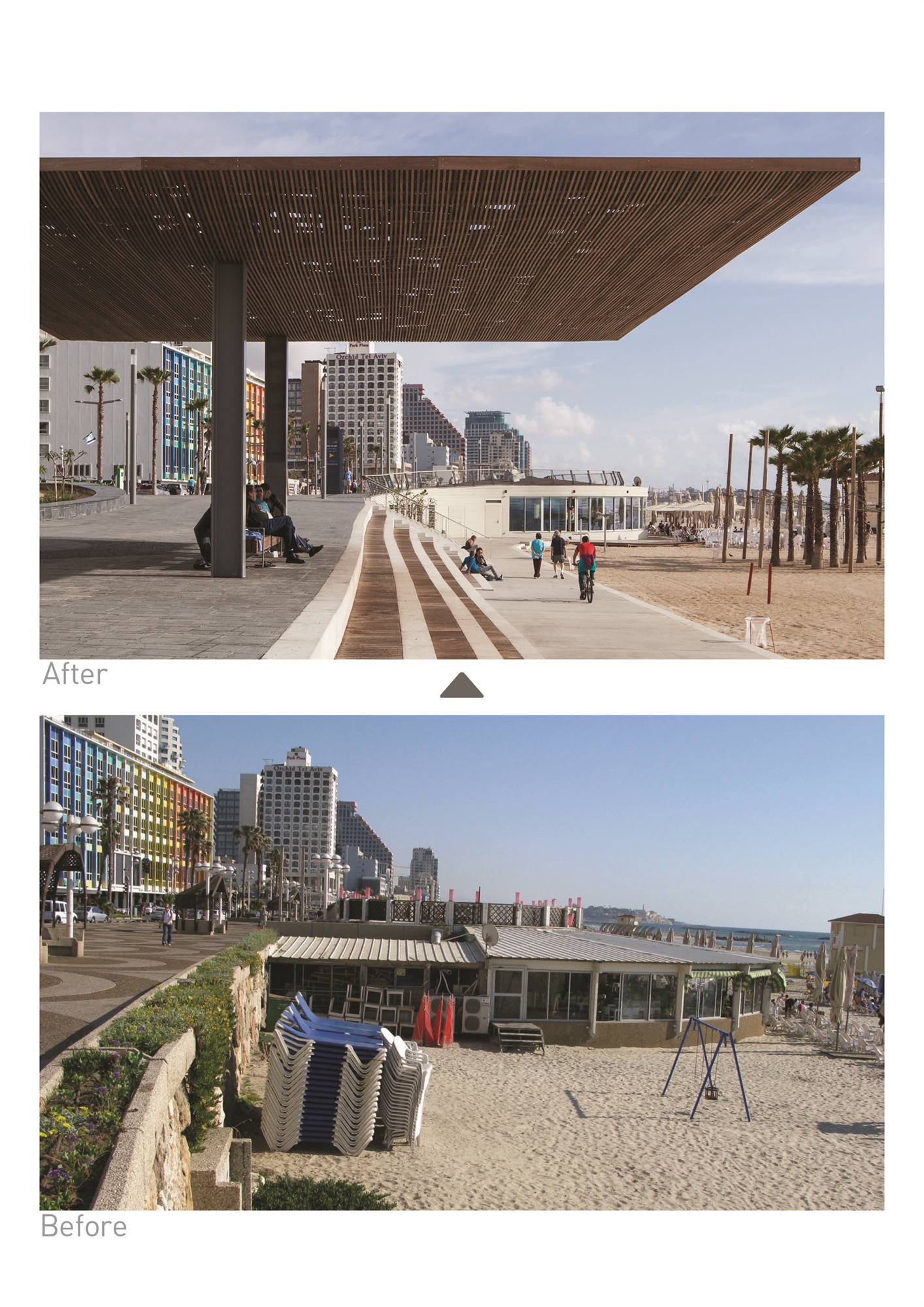

The success of the old port paved the way for the restoration of Tel Aviv’s central waterfront, which has now suffered greatly from time to time. “The tender was held in 2008, and the project was gradually handed over until 2018. It was a completely different case. Unlike the port, which was “closed” to the public, in the case of the central coast, we had to redesign a space that was already part of the life of the city. Therefore, we had to discuss and defend each of our choices. Why did we need all these levels, because we lowered the footpath to the level of sand,” explains Mr. Kassif.

“We held a referendum on our plans, proving that the public liked them. We finally succeeded.”

“The old boardwalk was beautiful, but it created a border between the coast and the city because it was raised. This border had to be removed. In addition, the space had to be multifunctional, be at the same time a place for rest and work, a place for walking and playing sports, as well as for entertainment, accessible to everyone. The construction was delayed a little, mainly due to the reaction of the environmental movement, which accused us of commercializing the coast, of destroying the environment. In fact, we lost a year due to litigation. Finally, we did a special environmental assessment to prove that the energy of the waves when they have a wall in front of them is much stronger, carrying sand into the sea, contrary to what we suggested, that is, creating steps on the level of the sand. We also held a referendum on our plans, proving that the citizens like them. We finally succeeded.”

I explain to him that the reaction in many ways reminds me of those in Athens against any major urban intervention, i.e. in the reconstruction of Ermu or the Apostle Paul. “During this period, we are restoring the entire coastline of Eilat (the only city in Israel on the Red Sea). At first, everyone was in favor, but when the bulldozers began to work, the townspeople were afraid that we were destroying the beach. Unfortunately, social media plays a big role in these cases, reactions take on dimensions and escalate… into digital uprisings, often full of fake news. The Ministry of the Environment intervened because of the uproar and although they approved the project, they asked us to review it. Finally, we have again managed to get the approval of the municipal council, and we are moving forward.”

The success of the reconstruction of the central embankment of Tel Aviv can be envied. “Millions of people visit every month, not only about 3 million residents of Tel Aviv, but also visitors from Israel and beyond,” notes Mr. Kassif. “But the main thing is that she created a new urban culture that did not exist before. There are people in swimsuits and people in suits in the area, each enjoying the coast in their own way.” What would you do differently today? “I would add more shadow,” he says without thinking.

I ask him about Tel Aviv’s most pressing problem: the lack of affordable housing. “This is the hottest issue. Tel Aviv prices are Manhattan prices, the cost in the city center is currently 120,000 shekels per square meter (about 34,000 euros). And the problem will get worse as the population of Israel is expected to double over the next 20 years,” he explains. “We believed in a liberal economy and capitalism for years, but now we realize that this is taking us in the opposite direction than we thought. Our responsibility is to provide citizens with housing that matches their financial capabilities. Israel “Wealthy country. The government should start a serious housing program to rent or sell affordable housing.”

The discussion ends in Athens, which Mr. Kassif frequently visits. “It has been calculated that investment in public spaces pays off tenfold within eight years. Athens is a beautiful city of fantastic scale, heritage, historical monuments: it has everything. What it lacks are several public spaces with an attractive modern design that allows you to spend the whole day there, feeling safe and welcome. Moreover, Athens needs more greenery, more soil, more nature. Nothing can replace big trees and permeable surfaces. Climate change is forcing us to seriously rethink these issues in all Mediterranean cities.”

Source: Kathimerini

Robert is an experienced journalist who has been covering the automobile industry for over a decade. He has a deep understanding of the latest technologies and trends in the industry and is known for his thorough and in-depth reporting.