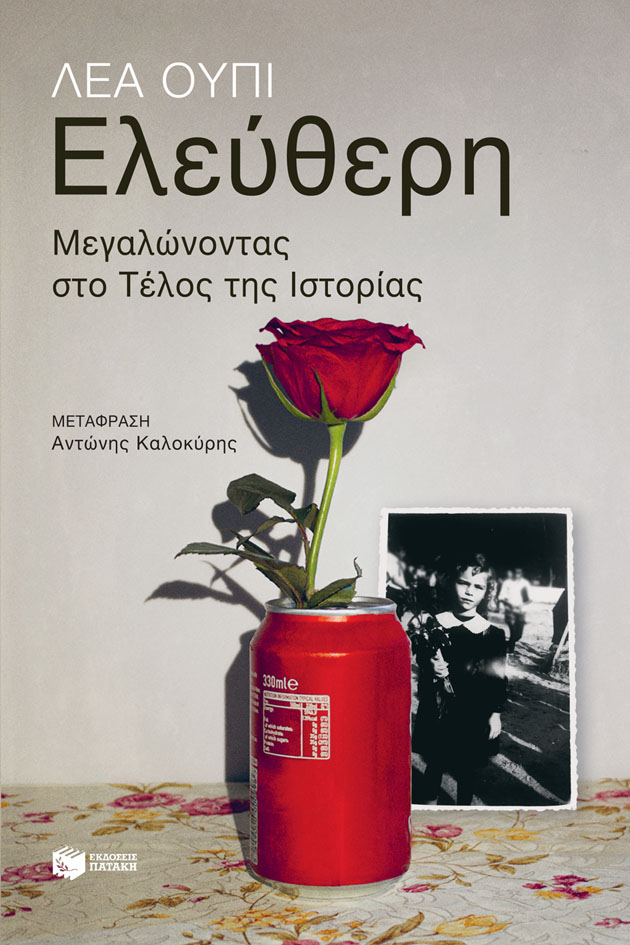

In her semi-autobiographical book Free, Growing Up at the End of History (published by Pataky), Lea Opie describes the fall of the communist regime in Albania through the innocent eyes of a child. This is something like the Albanian version of “Farewell, Lenin”, since the main character – in this case a minor – does not seem to suspect that existing socialism is collapsing around her. She remains attached to the statue of Stalin and “Father Enver” Hoxha, unaware of her family’s complex “CV”. Her great-grandfather was Xafer Upi, the former Prime Minister of Albania, who was disowned by the regime. However, she believes that she is connected only with the “enemy of the people” of the same name. Her family pronounces anti-Hoxha slogans in front of her and only in 1991, after the fall of the regime, dares to reveal to her that the country has been an endless prison of oppression and censorship. The traumatic civil war of 1997 forces her to reconsider everything, even the concept of freedom. She is currently a professor of political science at the London School of Economics and teaches the work of Karl Marx to her students. She is learning Greek to connect with her grandmother’s roots, spends half of her vacation in our country and admires Eleni Foureira. Her child is often ashamed to say that he is of Albanian origin.

– This point is not fiction at all. They really left me in the dark. I grew up striving to be a good citizen in communist Albania, not knowing that my family was a “class enemy”. It wasn’t until things started to change that I realized that the “class enemies” I was taught to hate were the people who had raised me. I started journaling, perhaps to deal with the confusion. Many details of the book are taken from the diary, which confirms how unprecedented it all was.

– I have two different relationships: one concerns the past, the other concerns the present. The first was bequeathed by my grandmother, who was born in Thessaloniki to an Albanian family and belonged to the Ottoman elite. My grandmother loved Thessaloniki very much, although she did not consider it a Greek city, although she herself spoke Greek fluently. For her, it was an Ottoman city, a multicultural melting pot that she left to move to Albania in her mid-thirties. When the communist regime fell, she returned to Thessaloniki, trying to recover the family property she had left behind, but failed. My second connection to Greece comes from the stories of Albanians who immigrated there after the fall of communism. Many of my compatriots changed their surnames and were baptized in Orthodoxy, because they thought that this would help them integrate. Many have faced racism or xenophobia. The economic crisis and the pandemic hit them hard. As for the success stories, I mentioned the participation of Eleni Foureira in Eurovision. But I read that she was born in Albania under the name Endela Furerai, and her story is as much about struggle as it is about success.

– We have the same history, we have a common Ottoman past, both countries fought against authoritarian regimes, the food is the same, and our temperament, if one can resort to generalizations, is very similar. The Albanians fought more than others for independence after the fall of the Ottoman Empire, and I would say that their nationalism is more defensive than expansionist. But it is always more constructive to focus on the present. I recently started learning Greek to better understand my family background and the history of my country. Most of my holidays are in Greece and Albania. Identities are not exclusive. We must resist those politicians who try to convince us otherwise.

When things started to change, I realized that the “class enemies” that I was taught to hate were the people who raised me.

– I wanted to write a story about freedom, in which many voices would sound freely, each with its own interpretation of events, its own value system and with conversations that do not try to answer readers’ questions, but only begin. I was determined to write non-paternalistically. Freedom is not taught. This is the journey you are on. The voice of the child is useful, and because the child has no identity of his own, he reproduces the opinions of others. He cannot be accused of manipulating anyone.

Everyone is free to interpret the book as they see fit. For me, the world is not divided into “exotic” and “non-exotic”. The criticism is based on the interpretation of the main components of life in Albania through a lens usually shaped by patterns that dominate outside my country. The book tried to do the opposite. Speaking about the local decoration of international symbols and cultural characteristics, he tried to give a voice to the Albanian citizens. Present them not as a group of brainwashed people, but as people.

– Brain drain is an epidemic for Albania. Unfortunately, there are no easy solutions. What is a win for rich countries, attracting skilled immigrants, is a loss for the poor. The only alternative is an appropriate development in which freedom of movement includes the freedom to stay at home. This suggests that immigration is seen not as a problem, but as a consequence of global injustice. To solve it, we need to rethink the global economic and political order.

– Recently, there has been a campaign of negative stereotypes and xenophobia directed against Albanians living in the UK. Children are extremely picky about such matters, and I know there have been discussions with my son’s friends about whether Albanians are “criminals”, as the British Home Office recently stated. The Albanians are the latest immigrant group to be demonized and dragged into a war of poor against poor to cover up the failure of the policy. The scenario is familiar, with immigrants being accused of damaging housing conditions despite countless evidence to the contrary. But I don’t think what’s happening in the UK is an exception. The names of those targeted may change, but the trend is the same across Europe.

– Yes, in order to know the world, roots are needed, but they are complex. If we could move away from the simplistic form of the state-centric, nationalist paradigm that, unfortunately, still shapes our educational systems, we would see how our roots are interconnected beyond national boundaries. History is often written by elites who come to power with narratives that exclude rather than include. We tend to believe these stories. But it is possible to go beyond the idea of a single homeland without undermining our cultural identity. Thus, we could accept cultural diversity as a source of power and wealth rather than a threat. We could belong to several communities and become citizens of the world.

Source: Kathimerini

Emma Shawn is a talented and accomplished author, known for his in-depth and thought-provoking writing on politics. She currently works as a writer at 247 news reel. With a passion for political analysis and a talent for breaking down complex issues, Emma’s writing provides readers with a unique and insightful perspective on current events.