Even in countries with friendly neighboring populations, Putin’s popularity is at an all-time low since his invasion of Ukraine. But what are the roots of sympathy for Putin? Is the way the Greeks see it changing?

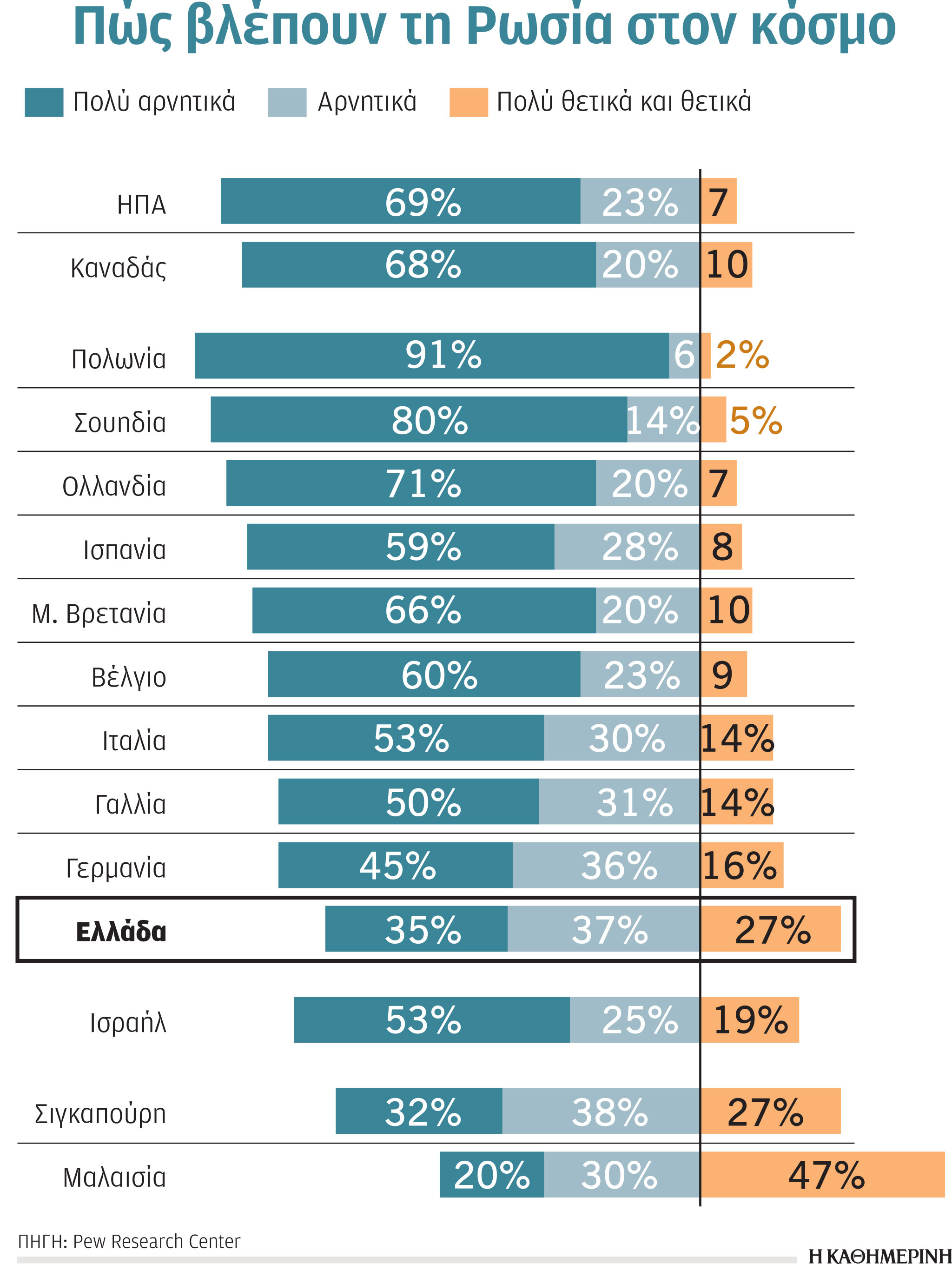

Russia’s fall in approval is being registered internationally – record highs in 2022 compared to 2020. If we take into account the findings published by the renowned think tank Pew Research Center, the blow to Russia’s image is now being felt even in 18 states that speak positively about the country . In Greece, her popularity fell by 31 percentage points. When the question takes on the character of confidence in Putin’s personality, the percentage of Greeks who disapprove of him “not at all or a little” now rises to 72%.

However, nearly 30% of Greeks who approve of Putin’s war in Ukraine are the third highest after Malaysia and Singapore. After all, not only Putin is losing popularity in Greece, but also Biden, whose percentage after the Russian invasion of Ukraine fell by 26% in our country, where his rating is the lowest – only 41%. The positive opinion about the United States as a whole also decreased by 15%, which, according to 63%, was a good reason to leave Afghanistan. Also in Greece, support for NATO has fallen even further, falling below an already low 38% in 2021. And one more thing: 33% of Greeks sympathize with Chinese President Xi Jinping.

Inevitably, the party choice of the Greeks, who have a favorable attitude towards the Russian “sambauke” in Ukraine, also enters into the discussion. Among supporters of the Greek solution, 55% openly support Putin’s foreign policy, and only 18% of Greeks who have turned their backs on Velopoulos’s party praise the behavior of the Russian leader.

But, perhaps, one should distinguish the popularity of Russia from the popularity of Putin. “There is a traditional undercurrent of sympathy and goodwill for Russia in Greek society for reasons we know well: cultural/religious reasons on the right, Cold War nostalgia on the left, broader anti-Westernism/anti-Americanism. However, Putin’s popularity as a person, I think, should be understood in the more specific context of the economic and political crises not only in Greece, but in Europe as a whole over the past decade. Admiration for a “strong leader” who knows how to “find solutions” and “play the game” I believe reflects a more general impatience with the workings (and mistakes, for that matter) of liberal democracy that has frustrated many citizens in recent years.” , Chatham House Partner, Angelos Chrysogelos, Associate Professor of International Relations at London Metropolitan University, highlights the “K” that finds Putin’s authoritarian policies in the minds of his supporters as opposed to the procedural, technocratic and often procrastinating logic that characterizes Western political systems, not to mention European Union: “This is a projection in the field of international relations of the frustrations that are also expressed within Western democracies – by the way, we are seeing a similar dynamics in Erdogan’s popularity in various countries where there is a deep disillusionment in the political system from Bosnia to Egypt and from Palestine to Somalia. This perhaps explains Putin’s popularity in countries that do not have Greek cultural ties to Russia, such as Italy and France, but have many of the same problems as Greece. From this perspective, and while we must take a hard line on Russia, we must not fall into the trap of seeing Putin’s popularity as a problem, but as a symptom of a deeper weakness in the modern citizen’s relationship with liberal democracy. Thus, a confrontation with Russia cannot serve as an excuse for ignoring these problems of legitimation of liberal democracy. Even if Putin’s image is tarnished, frustration will simply find another way out.”

Putin’s aura and the day after

But the war intervened. On the one hand, the image of the aggressor suffered against the backdrop of bombed cities, dead civilians, as well as economic side effects. On the other hand, Putin’s Russia still commands strong sympathy in Greek public opinion. “However, the question is not so much about sympathy for Putin, which can be restored after the war, but about the impression that many have of him as a strong leader who achieves something in the international arena. The development of the war so far has spoiled this aura of Putin as a maestro of international diplomacy, making him more “down to earth”, a normal politician who, even if his supporters see great successes (strengthening his relations with China and India, for example, or pressure on the EU on energy ) cannot ignore its failures: sanctions against Russia, its isolation from a large number of countries, heavy losses in the war. Of course, a lot will depend on the outcome of the war, but I have the impression that Putin, and with him his authoritarian style of government, which many saw as an alternative to the alternative liberal democracy model of power, has been seriously exposed.” he says.

Conclusion: The invasion of Ukraine dealt a blow to the image of Putin’s Russia, even among its supporters. But the roots of his “charm” are still there, and this should worry politicians in Athens and Brussels.

Source: Kathimerini

Robert is an experienced journalist who has been covering the automobile industry for over a decade. He has a deep understanding of the latest technologies and trends in the industry and is known for his thorough and in-depth reporting.