Those who have completed economics courses know that the (at first glance) simple question – How much does it cost? – has different answers depending on who you ask and why. Some will mention variable costs, fixed costs, direct costs, indirect costs, operating costs, opportunity costs, variable costs, etc. You’ll even hear answers about marginal or partial costs, sometimes mixed with PRICE (industrial or consumer) or value product. But it’s really important full costs what a company pays for a certain product.

In the case of electricity, integral costs have strategic and tactical importance in managing the national economy and balancing various needs, such as industrial competitiveness, efficiency and economic development, environmental protection, quality of life, energy security, etc.

The complexity of electrical systems is a reality due, among other things, to the fact that their operation is reliable if and only if the demand for electricity equals the supply of electricity at any time of the day or night. This unique characteristic of electrical systems is manifested in the formation of costs, variations of which have recently become political weapons disguised as economics in the fight against the “desecration of noble ideals” of the Paris Agreement and Green deal-s, in the implementation of the Net Zero policy simultaneously with the elimination of fossil fuels, followed by the electrification of transport, domestic and industrial consumption.

How are the various electricity costs calculated?

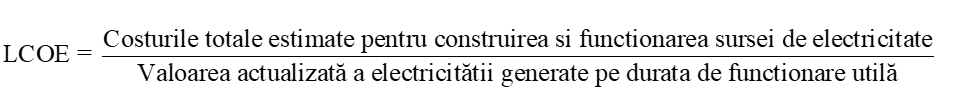

Among the existing methods,[1] recently most often used LCOE = Levelized cost of electricity:

LCOE based reports and analysis from organizations such as International Energy Agency (MEA), International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), National Laboratory of Renewable Energy (NREL), Agora Energiwende or the investment bank Lazard, are used by many governments to argue that a quasi-mandatory shift away from electricity generated from fossil sources to electricity generated by solar panels and wind turbines will save billions, if not thousands of billions of dollars globally.

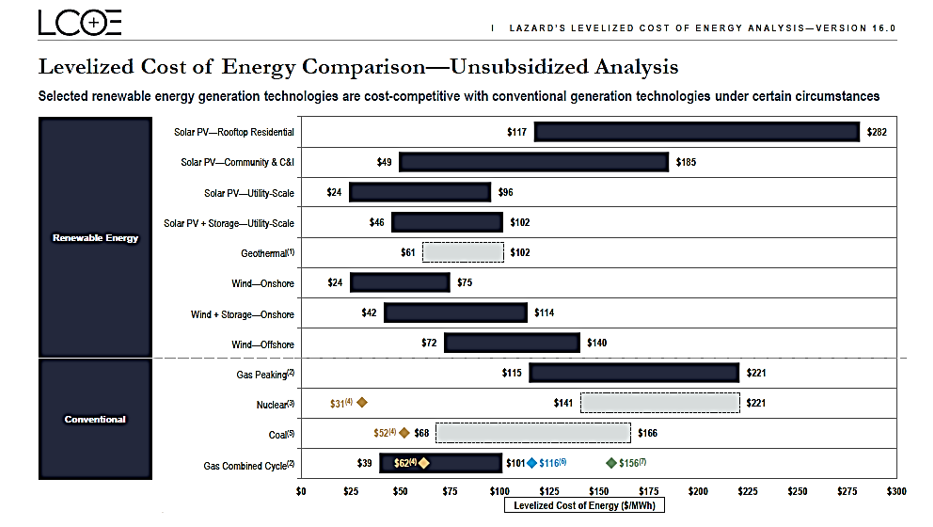

Lazard’s LCOE reports, launched in 2008, are notorious for their repeated and oft-quoted findings by climate journalists and environmental activists that wind turbines and solar panels have become the cheapest sources of electricity generation (Figure 1).

Fig. 1. LCOE estimate published by investment bank Lazard in the latest report for April 2023. PV = photovoltaic panels;

In the graph above, you can easily see that the LCOE of solar PV is $24-$96/MWh, the cost of onshore wind is even lower at $24-$75/MWh, and the cheapest fossil energy is combined cycle (steam) natural gas. + gas), which reaches $39 – $101/MWh.

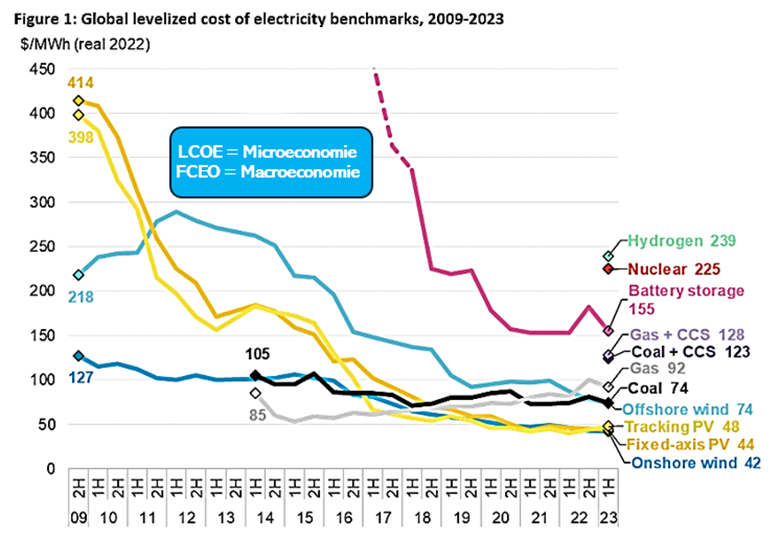

Consider another LCOE analysis published by Bloomberg New Energy Finance in June 2023. Graphs in fig. 2 have additional information: LCOE variations from 2009 to 2023; the cost of producing hydrogen (the most expensive form of energy at $239/MWh) and, very importantly, the cost of storing energy in batteries at $155/MWh, which exceeds all other forms except nuclear energy ($225/MWh MWh) and hydrogen. .

Fig. 2. LCOE cost estimation for different sources. CCS – capture and sequestration of CO2; PV – Photoelectric panels. Modified from BloombergNEF (2023).

And this LCOE estimate puts onshore wind and PV in the cheapest category ($42 – $48/MWh), while offshore wind produces electricity at a cost equal to the price of coal ($74/MWh).

So wind and solar electricity is cheaper than fossil fuel competitors! Is there anything else to prove? Yes, answering the question:

Why is it inappropriate to use LCOE to estimate the cost of electricity at the national level?

The three main requirements of a successful national energy policy were described in detail in the article The Trilemma of the Energy Transition – sustainability, affordability, security. On a national scale – electricity is a societal problem – balancing the three demands is a major challenge and therefore energy transition scenarios associated with the Great Green Leap must assess the ways in which resource supply, technology, economics, costs/prices , government policies and population behavior will affect the production, distribution and consumption of energy.

Governments, through their respective ministries, are trying – with more or less success – to strike a balance in the energy trilemma through consistent prioritization. Access to reliable energy is a fundamental problem; this must be ensured before assessing economic affordability. Only after achieving a balance between reliable energy supply and affordable price can the problems of environmental sustainability be seriously addressed.

If we base our transition decisions on LCOE estimates, which state that renewable electricity is the cheapest and has no environmental consequences, we risk a crucial economic misunderstanding with harmful consequences for energy policy.

LCOE is an estimate microeconomic electricity costs limited to only three components – Read the full article and comment on Contributors.ro

Source: Hot News

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.