If things are so simple – and known to everyone – why don’t we see them in practice (at least as of this writing)? The answer lies in three words: greed, ideology, fear. The greed of a business environment that benefits from perks and benefits; the ideology of a large part of analysts and economists; fear of the consequences of reforms on the part of the political class. Let’s analyze them one by one.

1. Greed of the beneficiary business environment

Whether it is micro-enterprise owners, PFAs, real estate firms, computer geeks who don’t pay income tax, builders or farmers who don’t pay social security contributions (but get free medical services) etc., they all find countless reasons for extending the preferential treatment they enjoy, with arguments such as:

1.1 “We are an industry/sector/type of company at the beginning of the journey, and at this stage we need the support of the state.”

However, the truth is that micro-enterprises have benefited from preferential treatment since 2002, computer workers since 2004, hotel and restaurant sector since 2017, construction sector since 2019 and only agriculture and food industry since 2022. the industry is assumed to exist indefinitely and at some point must be withdrawn.

1.2. “By applying reduced tax rates, there is recognition of the importance to the economy and society of the work that we, those involved in the favored industry, invest.”

The argument sounds false, since the importance for the economy has already been recognized due to the above-average wage level (in IT, construction) and due to the above-average profitability of the respective companies – but more on that in the final part of the article.

1.3. “If you cancel our tax breaks, we will move our company overseas.”

This argument is most egregious given that taxation in all EU countries, except Bulgaria, is significantly higher than in Romania. That is, we, companies, refuse to pay 10 percent salary tax (the lowest in Europe), but we have no problems paying taxes of 25, 30, 40 percent in other European countries…

The truth is, I’m looking forward (but not really hoping) to the day when an IT guy publicly admits that it’s a shame not to pay income tax on wages in the industry, or a builder publicly admits that it’s a shame to use their services in terms of medical benefits , for which they do not contribute to them, or the owner of 9 micro-enterprises (3 of him, 3 of his wife, 3 of his son), which he enjoys a lot of benefits, with a profit margin of well over 6% (calculation of income tax vs. sales tax).

2. The ideology of a significant part of analysts and economists

Unfortunately, many analysts and economists prefer to approach the issue of budget balance in an ideological way, while missing the relevance and scale of the specific problem that needs to be solved.

We hear more and more arguments like:

2.1. “At the stage of its development, Romania needs a minimal state. When we develop, we will afford a bigger state – and a bigger budget.”

This argument might have been valid in the early 2000s, when Romania’s GDP (at purchasing power parity) was 32% of the EU average, but not in 2023, when we reached a GDP (at purchasing power parity) of 72% of the EU average . The analysts we are talking about seem to deliberately forget that Romania is an EU member state, that is, a territory with strong state involvement in the redistribution zone. Preferring a reduced redistribution, in the American style, relevant analysts imagine that Romania will become a kind of USA; in fact, with a little redistribution, Romania would become a kind of Guatemala, Honduras or El Salvador. Apply minimal state theory to an Anglo-Saxon audience and you have the US; apply minimal state theory to a Latin American audience and you have Honduras. But maybe this is what is needed: to have the privilege of living in well-guarded areas, with police, private schools and hospitals, without any regard for the rest of the population…

2.2 “Any fiscal correction means an increase in taxes.”

It is the height of hypocrisy that those who defended the introduction of the flat rate in 2004-2005 are now advocating its de facto end in a regressive tax system. Let’s be clear: the abolition of tax credits does not mean an increase in taxation, but a return to normal economic life.

2.3. “We can achieve the necessary fiscal correction only by reducing budget expenditures.”

Those who say such things have problems with math. Despite the fact that the reform of special pensions would be desirable, its value does not exceed 0.85 percent of GDP. And above all, it cannot be done in a short time, without a transition period of several years. So, the budgetary gains from the reform of special pensions can be estimated at a maximum of 0.15-0.20 percent per year, while Romania currently needs 2 percent of GDP.

The situation is the same with excessive employment in the field of public administration, especially in the provinces. But taking into account that the total salary of state employees is about 8.5 percent of GDP, how much could the reform of the budget sphere give annually? Maybe 0.2-0.25 percent of GDP.

All this should be considered in the context, when investments in defense, climate, infrastructure will require significantly higher costs in the coming years than now. Thus, the reduction of the budget deficit in the expenditure part is more than illusory.

With tax revenues of only 27 percent of GDP (compared to 30 percent of GDP in the case of Bulgaria, respectively 35-36 percent of GDP in the case of the Czech Republic, Poland and Hungary), Romania cannot offer public spending below 36 percent of GDP. – 37 percent of GDP, and in the future the level of these expenses will inevitably increase, and therefore the need for a (massive) increase in budget revenues.

3. Politicians’ fears about the consequences of fiscal reform

This fear is to some extent justified, but we will try to dispel it with economic arguments. The truth is that politicians are now paying for years of populist politics in which they gave with both hands (and took with neither), instilling the pathetic mantra of “we’ll vote for those who gave us something” to the electorate. , worthy of an underdeveloped country.

The politicians’ arguments will be as follows:

3.1 “If we cancel tax breaks, many companies (especially SMEs) will go bankrupt, leading to mass unemployment.”

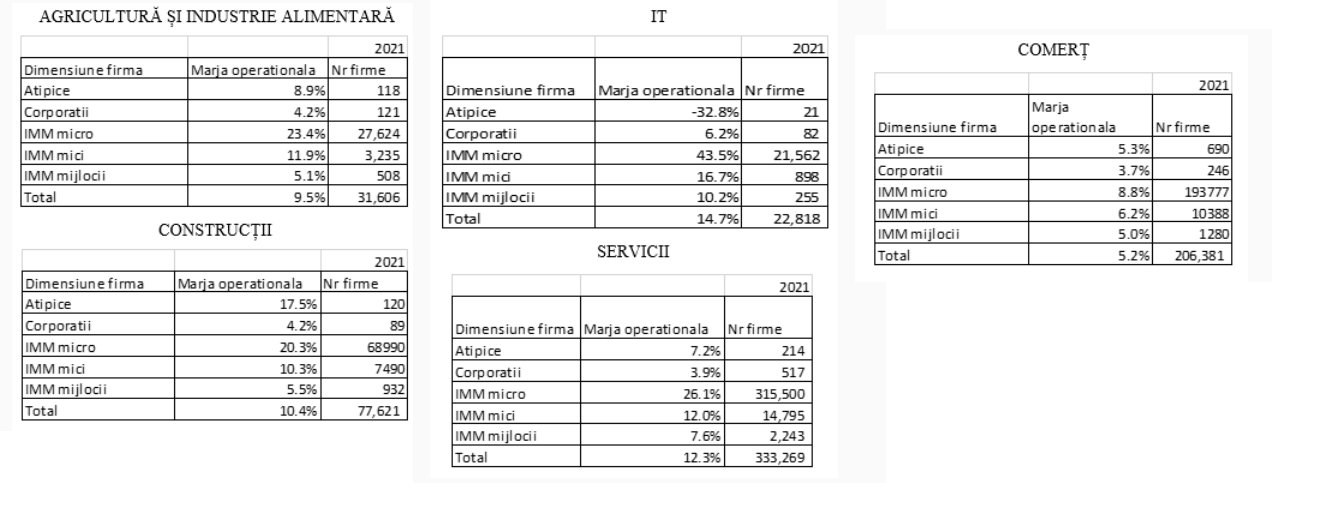

The following data (for which I am grateful to my colleague Florian Nyag) refute the above fears. For each of the industries analyzed (agriculture and food industry, construction, IT, services, trade) for all companies in 2021, the data show that:

– operating margin (defined as profit divided by turnover) is constant and ranges from 5.2 percent in the case of trade to 14.7 percent in the case of IT;

– SMEs usually have a higher operating margin than corporations in the same industry;

– among small and medium-sized enterprises, micro-SMEs have the largest operating margin, that is, precisely those that are considered the most vulnerable.

Thus, fears that increased taxation will hit mainly small players in the economy are not justified.

3.2. “If we cancel the tax breaks, we will put the economy into recession.”

Romania’s economy is currently growing at 2.4 percent per year, which is slightly below potential. But this is normal, because we have an excess of demand in relation to the domestic supply of goods and services. This excess demand creates inflation and external deficit. To eliminate it, ideally, it would be necessary to increase the domestic supply, but this is done slowly over time – and therefore the development of European funds is mandatory. Until then, restoring the economic balance requires restrictive monetary and fiscal measures, no matter how “impolitical” it sounds. After all, an economy car, like a car, is driven with both the brake and the accelerator, and not – as some hotheads would like – by constantly pressing only the accelerator.

In any case, we are far from recession (negative GDP growth) and even technical recession (negative growth for two quarters in a row).

3.3. “If we cancel tax breaks, extremist parties will win the next election.”

We can counter-argue that if the necessary measures are taken now, we will have both economic benefits (the deficit is lower than last year this year, and a deficit of about 4 percent of GDP in 2024 without additional measures) and political benefits (before the parliamentary and presidential elections in the fall of 2024, there is still enough time for the negative effect of the measures to dissipate,

On the contrary, if appropriate measures are not taken now, there is a growing risk that they will have to be taken in 2024, with serious electoral consequences. And the failure to take any measures neither in 2023 nor in 2024 will not make Romania the next candidate for receiving assistance from the IMF and for a possible suspension of funds from the European Commission.

À bon endendeur, hello!

ps Problem definition:

After the first five months of 2023, the budget deficit (on a cash basis) was 2.32 percent of GDP, which is about 0.8 percent of GDP higher than in the first five months of 2022. Under these conditions, if a number of measures are not taken urgently, the budget deficit at the end of 2023 risks exceeding 6 percent of GDP, that is, it will represent a regression compared to the deficit level of 5.7 percent of GDP recorded in 2022. It is easy to imagine the consternation this counter-performance will cause in Brussels and in the financial markets: a country that has promised to reduce its budget deficit to 4.4 percent of GDP this year, and which is unable to reduce even slightly the deficit compared to the previous year, perhaps for the first time at the EU level.

Next (mathematical) restriction:

To avoid the embarrassment of a lack of fiscal consolidation this year, Romania must implement a fiscal package equivalent to at least 2 percent of GDP from Sept. 1. Why 2% of GDP? Because applied in just the last 4 months (ie a third of this year), this package will reduce the budget deficit by around 0.67% of GDP, probably enough to drop – marginally – below last year’s deficit of 5.7% of GDP . It is also important to note that this package of 2 percent of GDP, if extended through 2024 (and without affecting other electoral “gifts”), will reduce the budget deficit to 4 percent of GDP next year without other additional measures, difficult to accept in an election year .

In the short term, the solution is to return to a true single quota that everyone claims but very few adhere to; due to numerous benefits and tax exemptions, Romania today has a regressive fiscal system in which those who earn more pay less to the budget. Eliminating these benefits and concessions could bring in more than 2 percent of GDP, which is what is needed to solve the fiscal problem.

PS Valentyn Lazeya is the chief economist of the National Bank. The text above is also published on the BNR blog.

Source: Hot News

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.