Alexandru Proca (October 16, 1897 – December 13, 1955), the most famous Romanian physicist, one of the creators of theoretical nuclear physics. [1], was born into a family of intellectuals from Bucharest, which produced mathematicians, doctors, writers. The environment in which he grew up and his intellectual qualities allowed him to master French, English and German languages perfectly by adolescence. His scientific debut took place at the age of 17, thanks to cooperation in the “Mathematical Gazette”.

During the holidays after his sophomore year in college, Romania enters the war, and Proca is mobilized – along with much of the student body. Accepted to the military school of reserve officers; graduated in April 1917 with the rank of second lieutenant engineer; he remained in the fire in June 1918. The feelings he experienced after the victorious end of the war, he shared with his colleagues in the generation through the pathetic “Letter to the Youth” [1]:

Give the generous rush of youth to the country!

Make, in the enthusiasm that inspires you, out of ardent love for the country, won in the trenches or in the sufferings of wandering, make a holy covenant to work for it, without prejudice, with all our strength, with all the zeal we are capable of. […]

And later, perhaps, I shall be granted to see you, my country, once more adorned with the jewels of virtue and wealth […]; oh, if only I could see you as you dream!

Proka resumes his studies, but not at the Faculty of Natural Sciences, but at the School of Bridges and Roads, the future Polytechnic School. He turns out to be an atypical student: he reads the lecture “Einstein’s Principle of Relativity”, addressing both colleagues and teachers; he also participates as part of a delegation of experts in visiting locomotive plants in Philadelphia, United States. The purpose of the visit is to select the type and quantity of electric motors that the Romanian state will purchase for the country’s needs.

He becomes an engineer, and the specialty recommends him for a position at the Electric Company, Câmpina branch. Proka learns about the country’s oil and mineral extraction methods and writes two papers to improve two fields. At the same time, he works as an assistant at the Department of Electric Power Engineering of the Polytechnic and as an editor of the article Herald of pure and applied mathematicswhich after a few years will turn into a French-language edition with a slightly changed name.

In the fall of 1923, he decided to go to Paris. “It seems to me that I have something to say about physics,” – with these words he motivates his decision.

Arrival in France

Proka arrived in Paris in October 1923. He discovers that the Romanian engineering diploma is not recognized in France, and to make it equivalent, it is necessary to pass all the exams, calculated over four years. Proka completes them in one, with scores close to the maximum.

A year later, Madame Curie offered him a position at the famous Radium Institute, which he managed together with Jean Perrin (Nobel Prize 1926). The atmosphere here is not strictly scientific, but contaminated with Parisian charm:

Receptions were held every Monday, famous and intimate at the same time […] tea was prepared by boiling in a glass flask with a stopcock over a metal grate that spread the flame of a Bunsen lamp. Tea was to be drunk from conical laboratory beakers, and glass sticks were used instead of teaspoons. There you could meet his students and colleagues, Joliot, Salomon Rosenblum, the Romanian theorist Alexandra Proca, Pierre Auger [descoperitorul efectului omonim]writers Paul Valéry, André Gide, André Morois, Edme de la Rochefoucauld… [2]

About Proka’s work at the institute, Ms. Curie says the following [1]:

Whenever I am faced with a complex scientific problem that requires great patience, competence, experimental skill and meticulousness, I turn to Mr. Proka. And he responds every time with appropriate solutions that satisfy me and always produce accurate results.

But not all researchers at the institute are equally enthusiastic about Proka; some probably see it as a threat. Household appliances left by Proka in working condition turn out to be faulty after a few days.

Sensing perhaps such animosity, but also Proca’s talent as a theoretician, Madame Curie facilitated his transfer to the Institut Henri Poincaré, established in 1928-29 with the financial support of the Rockefeller Foundation. Confident of his chances of gaining access to a university chair, Proca applied for French citizenship, which he received in 1931.

Relations with Louis de Broglie

The first work published in France, carried out at the Radio Institute, is experimental, but Proka’s vocation is mainly theoretical. Shortly after moving to the Henri Poincaré Institute, Proca enrolled for a doctoral degree (1930), whose scientific supervisor was Louis de Broglie (1892 – 1987), a recent Nobel laureate (1929), for the discovery of a fundamental property of quantum objects: particle-wave dualism ( 1923). Namely, any quantum object behaves as a wave and as a corpuscle.

Oddly enough, this ingenious idea is completely unique to de Broglie’s work. For the next 64 years of his life, the laureate of 1929 did not create a single successful work.

The topic of Prock’s dissertation was proposed by de Broglie and consists in the study of the electron in relativistic quantum mechanics. The dissertation—brilliant—was defended in 1933 before a committee chaired by Jean Perrin, the examiners being Léon Brillouin and Louis de Broglie. The thesis bears the unmistakable stamp of Proc: corpuscular dualism – a wave does not necessarily manifest itself in the sense previously defined by de Broglie.

This separation from the canonical concept adopted in French physics arouses the antipathy of de Broglie, who sees the originality of Proc’s ideas as a threat to his results, which he considers infallible. The treacherously camouflaged antipathy that the calm Proca felt only two decades later when he was denied a university chair, twice, at the Sorbonne and at the Collège de France.

Proka’s scientific results are too complex to be presented in a journalistic environment, so they will not be considered in the following lines. The interested reader can consult, for the first information, the works of Professor, Dr. Dumitru Mihalace, mc of AR [3], [4].

War

In the summer of 1939, Proka was mobilized. His rank of junior lieutenant, obtained in Romania, is not recognized, and he is classified as an ordinary soldier. As Proca became secretary of the French Society of Electricians and the International Conference of High Power Transmission Lines, the General Staff corrects the error: Proca will be used for transmissions. In the near future, he will assume the position of chief engineer of French radio broadcasting.

In 1943, the University of Porto invited him to hold a series of conferences. He was later invited by the Royal Society in London and the British Admiralty in England to join the war effort. It is not known (at least to the general public) what Proca’s contribution to this effort was, but it is known that his great joy was visits to Dirac, who lived near Oxford.

Proc’s seminar

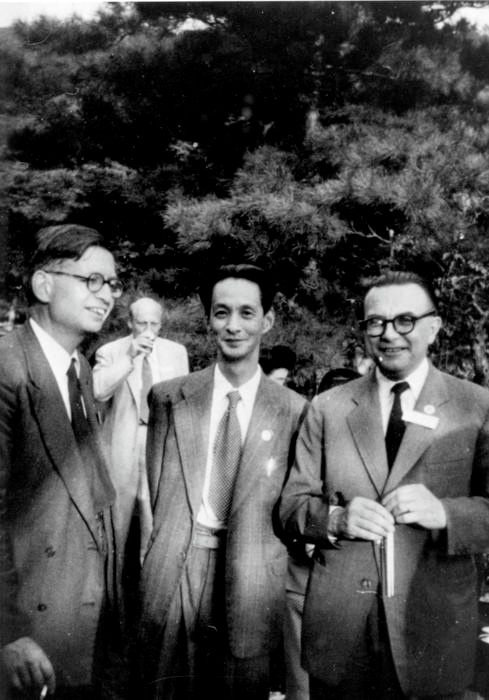

If for American and English physicists, the war years meant feverish scientific activity, for the French they meant stagnation and provincialization. Sensing this painful gap, Proka opens a seminar (1946-1955) that will bear his name. Among the many celebrities who participated in Prock’s seminar, we will mention only the Nobel laureates Born, Dirac, Pauli, Rabi, Tomonaga, Yukawa and – posthumously (after 1955) – Bethe and Salam.

Due to its tendency to counteract the effects of war, the Proca seminar seems like a pendant Letters foryoung since 1918, – believes George Proka, the son of an outstanding scientist.

The Nobel Prize

In 1949, Yukawa received the Nobel Prize in Physics “for predicting the existence of mesons on the basis of theoretical works on nuclear forces.”

In 1941, Wolfgang Pauli, one of the fathers of quantum mechanics, formulated the following opinion in an article published in the prestigious journal Reviews of Modern Physics:

“Theory [elaborata de Yukawa] for this case [al expresiei forţei nucleare dintre proton şi neutron] gave Proc”.

Obviously, Pauli’s opinion cannot be suspected of any partisanship; so we quoted her to try to answer the question: was Proca wronged by not sharing the Nobel Prize with Yukawa? If the answer is yes, then who is responsible for this injustice?

Regarding the first question: tradition and practice show that Nobel Prizes are awarded individually when the credit for the discovery is overwhelmingly attributed to one person; this is Einstein’s case with any of his great discoveries; or Roentgen with X-rays When an important scientific advance is achieved by the comparable efforts of several persons, no more than three of them may receive the award; this is the case of Tomonaga, Schwinger and Feynman, who received the Nobel Prize in 1965 “for fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics”.[5].

Regarding the second question: tradition requires that possible candidates be presented to the Nobel Foundation by a Nobel laureate of the same nationality – if there is one – and preferably of the same specialty. In the case of France, both qualities were present in the person of Louis de Broglie, but the treacherous hostility he showed to Proca made him incompatible with such initiatives.

Finally, it was natural for the country of origin to have lobbying activities, but the government in Bucharest did not have such issues on its agenda (a funny example of the Soviet lobby was described by Feynman [6]).

At the same time, Proka’s modesty and elegance were incompatible with any form of self-promotion.

It should be noted that the non-attachment of Proka to the prize awarded to Yukava is not the only and not the most serious anomaly in the decisions of the Nobel Foundation. One of the losers is Goudsmith, co-discoverer of electron spin with Stern; of the two, only Stern won the award. It’s a bit funny – losers Prock and Goudsmith are co-authors of a paper on quantum mechanics [7].

A very notable aspect of the Yukawa-Prock dilemma is that the discrepancy in awarding the prize led not to enmity but to growing harmony between Prock and Japanese physicists. Proka did not give the applicant any comments about the award – even in his own family, as his son’s biographical study shows [8]. The first researcher to apply for an internship at the Proca workshop was Professor Araki from Kyoto University, where Yukawa also worked; Yukawa himself lectured at Prock’s seminar.

Horiya Khulubey’s testimony regarding Proka’s visit to Japan in 1954 is also interesting. [9]. In those years of very few scientific visits to Eastern countries, Khulubey met the Japanese physicist Fujioka at a meeting of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR, who told him that “the Japanese invited Alexandra Proka to them for a series of conferences. and to honor the man who, together with Yukawa, laid the foundations for the study of meson fields. Mr. Fujioka told me what a wonderful impression Alexander Proka made among Japanese scientists, what love he was surrounded by and what respect they had for the work of our fellow countryman.” Read the whole article and comment on Contributors.ro

Source: Hot News RU

Robert is an experienced journalist who has been covering the automobile industry for over a decade. He has a deep understanding of the latest technologies and trends in the industry and is known for his thorough and in-depth reporting.