Yesterday we showed here why it is important to understand and measure China’s influence in different states, and for us in Bucharest it is a priority to understand how it operates in Europe. This is exactly what we set out to do “China Index” project., developed and managed by the well-known Doublethink Lab in Taipei, which is engaged in the fight against disinformation and digital security. Through the network of local coordinators and analysts, 82 countries of the world were covered in 2022. Each was X-rayed using 99 indicators of the influence of the Beijing regime, grouped into nine categories: science, domestic politics, economy, diplomacy, police and internal affairs, mass media, military relations, society and technology. The full database of results can be found here.

EFOR participated in this project and conducted analysis and evaluations for five European countries: Romania, Moldova, Ukraine, Italy and the Netherlands with the help of local analysts. So in my portfolio there was a difficult and interesting case of Ukraine, which got into a complex and dynamic ballet with Beijing. Significant economic and investment relations with China, which firmly placed Ukraine on the path of interest Belt and Road due to geography, which was with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) until the escalation of Russian aggression in February 2022, has today created a stalemate in which Kyiv and Beijing view each other with suspicion, but avoid open attacks on each other diplomatically in the hope of future cooperation

China had significant investments in Ukraine in agribusiness, ports and industrial production (in Mariupol) and these were badly affected by the war, but also the attempt to take over the Zaporizhia Aircraft Plant, blocked by the government from Kyiv in 2022, which caused a lot of discontent in Beijing. We presented this landmark case of Ukraine at the launch conference of the China Index project in December 2022 in Berlin. The project is ongoing and we are in the middle of data collection and analysis for the 2023 round, when the scores for the existing 82 countries will be revised and several new ones will be added (including Russia); the final total will probably be around 100.

Romania it’s not a country that China has shown much interest in over the past decades, which has somewhat made things easier for them today. To some extent, this is also a regional symptom: apart from rhetoric and symbolism, such as the 16+1 initiative launched in 2012, little has happened in relations between China and Eastern Europe over the past ten years. Probably, the Chinese business environment quickly realized that there is nothing to buy or spy on technology in the new EU member states, since the most important industrial assets, however few, were privatized by Western partners in the 90s. The economic complementarity of these countries with China is low, their internal markets are small, and after their accession to the EU, even agricultural quasi-colonies can no longer become for Beijing, since agriculture practiced here according to EU standards generates more expensive products than elsewhere. . Thus, after years of polite rhetoric, the “16+1” format of regional cooperation remained an empty content shell destined to be forgotten. Read more about these developments here.

On the other hand, governments in Bucharest in recent years have been able to adopt restrictive policies towards Chinese companies in several sensitive sectors that would really interest Beijing, practically excluding their participation in important technological projects (ITC-5G), correctly analyzing and rejecting the economically unfeasible ideas of the PRC invest in large energy infrastructure, such as the Cernavoda nuclear power plant or the utopian Tarnica hydroelectric plant. In addition, Chinese companies are limited in their ability to participate in public works tenders. But at the same time, Romanian officials have avoided publicly doing or saying anything that could unsettle the leaders of the PRC, or initiate a rapprochement with the Democratic Republic of China – i.e. Taiwan (just as they have carefully avoided participating in public discussion of the results of this project, or at least give any sign that they know of its existence!) In other words, we are in the famous schizoid-Romanian “we do but don’t say in public” posture, doing the job of an analyst who has to interpret the government’s motivations and strategies.

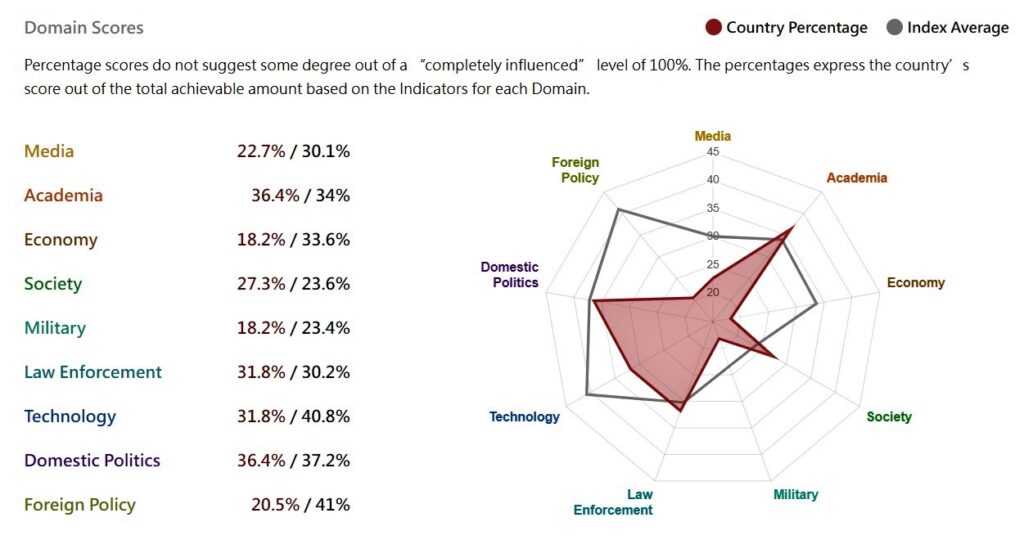

All this explains the rather low assessment of China’s influence in Romania, as measured by the China Index project: 107 out of a maximum of 396, which puts it in 53rd place out of 82 countries analyzed. The table below shows the scores for each of the nine areas of analysis. We believe that the most successful mechanism of influence of the PRC in our country is the co-optation of the political or academic elite, which is also confirmed by many anecdotal observations or reports in the press. Separately, it should be noted that among the political elite, influence activities often take place behind the radar, among political leaders at the level of districts or mayors of large cities, or in youth organizations of parties.

This is effectively a permanent strategy of the United Front (an organization coordinated by the CPC Central Committee with over 40,000 employees and a secret budget that directs the work of organizing and influencing non-CCP members at home or abroad) and applies to everything, not only in Romania: political organizations at the sub-national level, university rectors or second-line business leaders are being targeted. By comparison, the Beijing regime’s investment in spreading propaganda in the mass media or influencing society at large (for example, through cultural events promoting Chinese culture or direct human relations) is much smaller. Military cooperation is naturally excluded, given the alliances that Romania is part of, as well as the influence on diplomacy in terms of specific actions, such as voting in international institutions.

By further grouping the nine areas of analysis into three categories, we can use the Chinese index scores to obtain an even more interesting comparative picture between countries. Thus, we discovered that there are three significant clusters of states on the globe from the point of view of relations with the PRC:

1. Powerful states with which relations are hostile or at least acrimonious: for example, Australia or the USA in the graphs below. These states have a Contact intensified under the influence of the PRC (trade, mutual investment, the presence of a large diaspora) and the regime in Beijing makes Pressure seriously influence them in various ways. but Effect it is modest because these countries have the capacity to create an equally strong counter-reaction.

2. Weak states or in special situations where we can almost talk about a invitation China to exert influence without much opposition: Pakistan (otherwise the country with the highest CI in the world) or Venezuela. Here, China’s presence is perceived as positive, whether sincerely or from different political calculations of the ruling elite.

3. States are rather in a state mutual indifference with the Beijing regime, for different reasons: here it does not make a great effort to be present and influence, nor are the consequences great. Many times in international databases, China’s projects, under the auspices of the Belt and Road (BRI) or otherwise, appear against these states with a date of 2023, which was never realized or was unrealistic from the start. This shows that even international analysts who specialize in China are in no hurry to update information on these uninteresting areas. Romania fits this category quite well. – Read the entire article and comment on Contributors.ro

Source: Hot News

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.