Inflation has recently returned in Romania, and there are few signs that this phenomenon will abate, despite optimistic statements from the authorities. Recent developments seem to point to the possibility of a price-wage spiral, which will contribute significantly to increasing inflationary pressures.

A price-wage spiral is a phenomenon where rising prices lead to rising wages, which in turn lead to rising prices, leading to new demands for higher wages, and so on. This phenomenon usually occurs when the labor market is unbalanced in the sense that there is a labor shortage and employers must raise wages to attract and/or retain workers. As a result, there is an increase in the cost of production of goods and services, which leads to an increase in the prices of consumer goods. As prices rise, workers will demand higher wages to maintain their purchasing power, which further raises production costs and prices, and the cycle repeats itself with ever-higher rates.

A separate case is when the price-wage spiral is triggered by a wage increase in the public sector. In this case, there is both direct and indirect influence. First, there is an immediate increase in aggregate demand, which directly pushes prices up. The second manifests itself in the fact that the growth of wages in the budgetary sphere leads to the growth of wages in the production sphere, because employers are forced to raise wages in turn, so that the labor force does not leave them and does not migrate into the population. sector An increase in the minimum wage and social benefits has similar consequences – direct and indirect.

An important indication of the emergence of a spiral of prices and wages is the preservation and strengthening of inflation, which is accompanied by the disappointment of inflationary expectations. The first impetus is given by the growth of the inflation rate faster than the growth of wages and, accordingly, labor productivity. Such sequences are very likely if the labor market is tight or wage increases occur in sectors whose activities cannot be stopped because they block the entire economy and society (transportation, health care, education, etc.), giving workers and the relevant union leaders a great deal of leverage. bargaining power However, wage growth may continue even if purchasing power stops falling, as wage earners try to recoup previously experienced losses in purchasing power and protect themselves against future inflationary surprises. […]

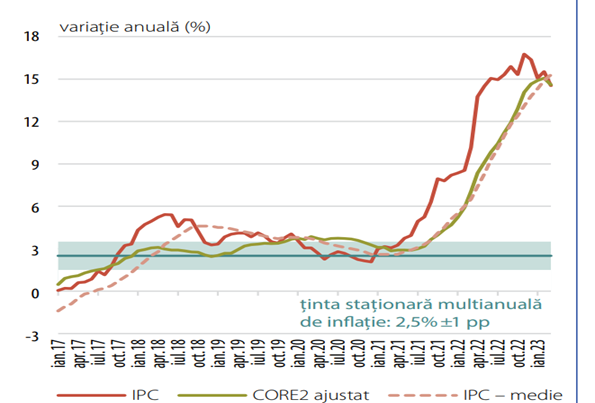

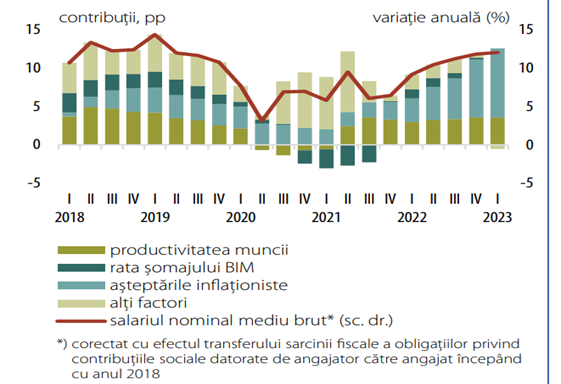

As can be seen from the graphs above, the annual rate of inflation (Consumer Price Index) reached 16.76% in November 2022, after which it started to decrease slightly, reaching 14.53% in March 2023. The annual growth rate of average gross wages in the economy increased in the period January-February 2023, reaching 13.1%, compared with 11.7% and 12.2%, respectively, in the last two quarters of 2022. This growth was driven by events in the private sector (15.7% in the first two months of 2023) as a result of the authorities’ decision to raise the minimum wage (approximately 33% in construction, correspondingly almost 18% in other sectors of the economy), which was a form of implicit adjustment of salaries with the level of inflation. The acceleration of wage growth is also explained by inflationary expectations (Fig. 2 and Fig. 4), while labor productivity and the degree of tension in the labor market had a minor contribution to the dynamics of wages (Fig. 2). In the public sector, the rate of wage growth remained moderate, but in January-February 2023 growth was recorded at 5% (from 3.7% in the last quarter of the previous year) as a result of higher wages in public administration and education. It remains to be seen what the consequences of the recent emergency government order to increase teachers’ salaries will be.

Prerequisites of the wage-price spiral

The spiral of prices and wages implies the existence of a Feedback between prices and wages. This two-way relationship leads to a constant rise in inflation without wage growth necessarily keeping pace with price growth. When the economy enters a vicious cycle, workers demand an increase in nominal wages more than the price increase that has already occurred, forcing firms to raise prices further. After that, the opportunities for salary increases diminish, leaving only inflation and its destructive consequences.

The likelihood that an economy will fall into a price-wage spiral depends to some extent on macroeconomic conditions. The bargaining power of workers or their union representatives is usually greater when the demand for labor is high and the supply of labor is limited. Likewise, firms have more pricing power when demand for consumer goods and services is high.

The likelihood of a price-wage spiral is also influenced by labor market institutions. Provisions for automatic wage indexation, for example, make spiraling growth more likely. Wage agreements involving large groups of workers also have a strong ripple effect. Thus, public sector unions can more easily negotiate wage increases with strong spillover effects on private sector wages. Finally, an increase in the minimum wage, motivated by the preservation of workers’ purchasing power, can have the effect of raising all wages.

In the manufacturing sector, an important factor is the degree of competition. Firms with a larger market share can more easily raise prices when wages rise, while smaller firms may, for various reasons, be reluctant to do the same. The pricing strategies used by different businesses also matter. Firms are more likely to raise prices if they believe their competitors will do the same. Price increases are easier to implement when demand for the goods in question is high or inelastic. And even firms with little pricing power can pass on rising labor costs to customers if they don’t fear shrinking sales and can maintain their profit margins.

The background against which all these forces operate is monetary policy. A credible central bank that takes appropriate action in response to changing macroeconomic conditions and communicates well with society effectively helps anchor inflation expectations. This softening of pessimistic expectations weakens the reasons why workers want to demand higher nominal wages and firms want to raise prices. And even though workers may still struggle to get wage increases to recoup past losses from inflation, the intensity Feedback– the price-salary decreases. Well-established expectations make approx Feedbackthe shorter duration mentioned is because economic agents expect inflation to return to the inflation target announced by the central bank.

Are there conditions for a price-salary spiral?

From several points of view, the current situation in Romania seems favorable for such a spiral. Although the correlation between wage growth and inflation currently has a low intensity (Figure #1 and Figure #2), recently this relationship seems to be strengthening.

As, for example, the teachers’ strike ended, public sector unions have strong collective bargaining power over wages. Similarly, decisions and promises to adjust wages to inflation have increased recently, fueling price-wage spirals in the past, and are likely to increase in the run-up to the election. It is also noted that the number of employees in state institutions and authorities has increased, where salaries are approx. 30% higher than in the private sector. However, all these facts show that the labor market conditions in Romania are favorable for a spiral. In other words, inflation appears to have started to take hold.

There are other forces that make price and wage spirals more likely. The pricing power of firms is high due to the large number of companies with full or majority state capital (over 1,100), many of which occupy a monopoly position. In conditions of low inflation, the possibility of transferring wage costs to prices is small, even for this type of enterprise. But in an inflationary environment, the large size, monopoly position, and political support of state-owned enterprises can contribute to inflation because the management of these enterprises, often called politicians, pays more attention to wage growth and factors that growth into their pricing decisions. This characteristic of Romania’s economy, which is a consequence of the failure to complete the reforms necessary to establish a market economy, is one of the important reasons why inflationary pressures may increase in sectors that have not been blocked either by the pandemic or by strikes and demonstrations.

The authorities, of course, are trying to defuse inflationary expectations. The NDB’s latest forecast points to inflation at 7.1% at the end of the current year, later falling to 4.2% in December 2024 and 3.9% in March 2025. The newly appointed government also states that one of its goals is to reduce inflation. The problem is that risk and uncertainty remain particularly high, fueling the price-wage spiral.

The risk of spreading pressure on wages

In light of what has been shown, the question arises as to whether the wage increases that have already taken place in Romania could trigger a price-wage spiral. In view of the above reasons, it is necessary to pay special attention to a significant increase in wages in the public sector and the minimum wage in the economy.

Experience shows that significant increases in some wages, especially in the public sector and in enterprises with full or majority state capital, quickly spread to other sectors. Historically, such increases were frequent, especially in the early years of transition, but this phenomenon has reappeared and may have the same dire consequences as in the past (annual inflation reached 256.1% in 1993).

In addition, increased migration from one job to another, undeclared work, hidden wage increases, etc. can lead to a rapid spread of intersectoral spillovers and reconfiguration of the labor market. The large number of workers being laid off may cause some sectors, such as the manufacturing sector, to respond by raising nominal wages faster than in the past.

The implication is that although increases in public sector wages and the minimum wage in the economy have not yet led to significant increases in all wages, these increases are likely to trigger a wage-price spiral.

Therefore, the essential question that arises is whether the relationships of this nature described by the theory and observed, including in post-communist Romania, will be repeated in the near future, when inflation is likely to remain high. Obviously, salary requirements have recently increased many times. In turn, pressure to raise the minimum wage may intensify, citing, among other things, the example of some EU countries that have already done so, as inflation remains high in the eurozone as well. A public sector wage set through collective bargaining with an employer that does not pay wages out of pocket and has a strong electoral motivation can serve as a benchmark for setting wages in the private sector. And if these wage increases continue, the consequences for wages and prices could be much greater than in the past, when inflation was low. – Read the entire article and comment on Contributors.ro.

Source: Hot News

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.