65,549 fewer people, roughly the population of a city like Lamia, was the average annual retail employment in 2020 compared to 2009, just before the onset of the economic crisis. And this is only one side of the imprint left by the economic crisis and then by the pandemic crisis on the country’s largest employer, retail, an imprint expressed not only in quantitative but also in many qualitative characteristics. In essence, the economic crisis has triggered a tectonic shift in retail that has added to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic. Employment has declined, but characteristics have also changed, the number of lockouts has actually exceeded 50,000, and the cumulative loss of net profit from the sector – excluding VAT – has exceeded 17 billion euros, equivalent to 8.17% of GDP.

In addition to the thousands of very small businesses that did not survive during the financial crisis, entire retail chains disappeared from the business map of the country. According to a good scenario – like Marinopoulos and Veropoulos – the stores changed their name, but the jobs were preserved. In many other cases, however, businesses have closed, leaving hundreds of workers unemployed, such as those who worked at the Electronics Athena chain of electronics stores, Glou and Fokas clothing chains, Neoset, Sprider Stores, and many others.

A layoff of 65,549 employees, 50,000 lockouts and a loss of $17 billion in revenue is the account of the industry’s great recession.

The fact that as a percentage of the total number of retail micro-enterprises, i.e. with one employee and between 2 and 9 employees, remained at the same level in 2020 compared to 2009 does not reveal the whole truth . First, many thousands of individual entrepreneurs closed during the years of the economic crisis and many opened in their place. Even in 2019, when the Greek economy emerged from the memorandum regime and became a year of significant growth of new businesses, the main motivation for starting a business remained the creation of more income and livelihood. In particular, 51.6% at the time answered that the main motivation is to earn a living, since there were few jobs, and the motivation to earn more income came in second with 48.2%.

It is for the above reason that the numbers do not always tell the truth, especially for small retail businesses. Rather, they reveal half the truth. According to ELSTAT, in 2009, out of 187,870 retailers, the number of employees under 9 was 183,773, i.е. approximately 97.8%, and in 2020, out of a total of 139,181 enterprises with up to 9 employees, it was 135,519, i.e. 97.36%. In other words, the share of small businesses in all retail businesses has remained the same, which is related both to the need for livelihoods, as discussed above, and to the structure of the Greek economy.

However, what has changed significantly as a result of the crisis is the structure of retail employment. Thus, if in 2009 the number of entrepreneurs and unpaid family members was 245,609 people out of a total number of 500,465 people employed in the industry, i.e. 49.07%, then in 2020 the corresponding percentage decreased to 33.49%. In other words, employers and the family members they helped have largely become employees.

The crisis has become an opportunity for supermarkets

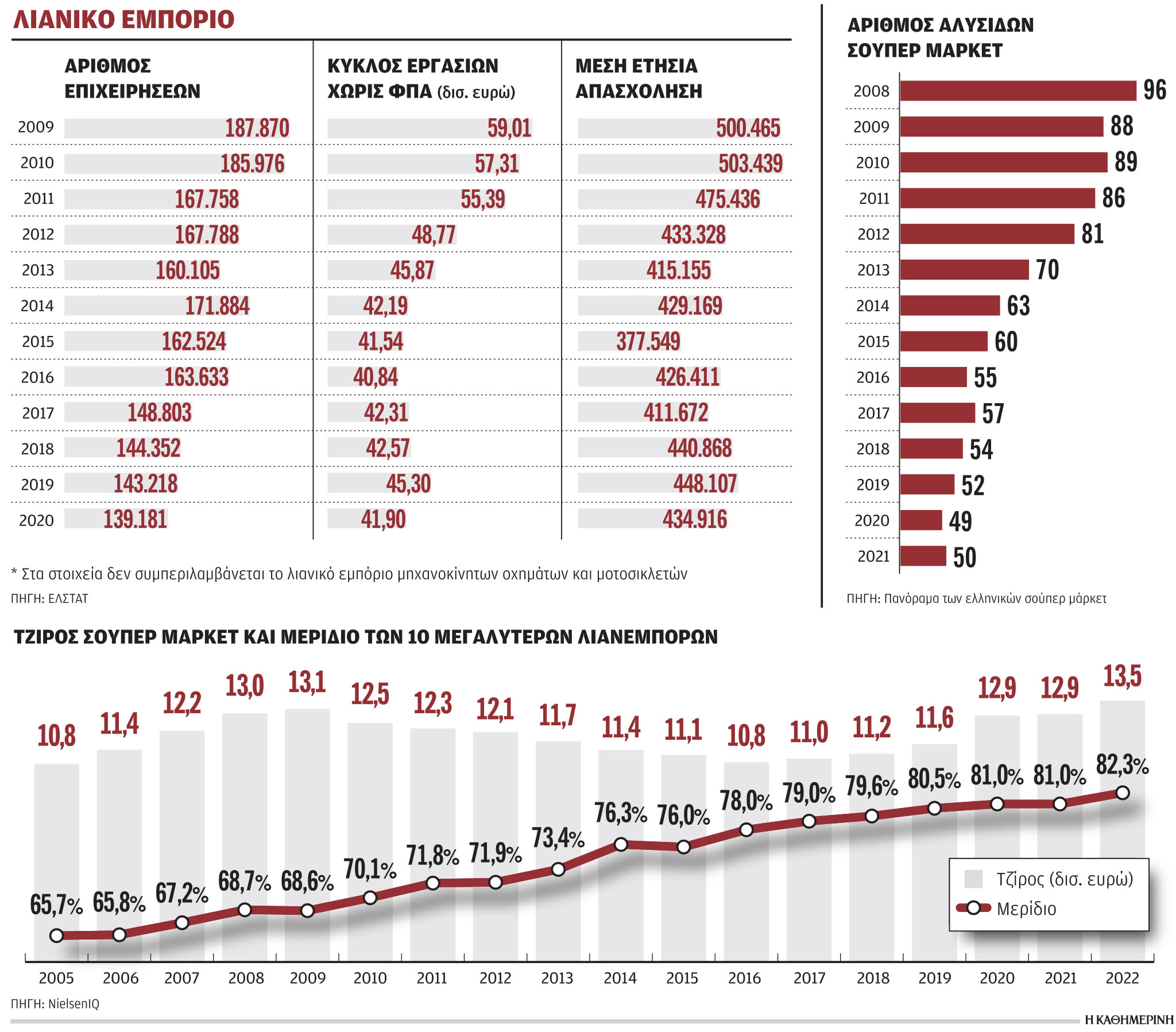

Supermarket turnover and concentration in the sector have evolved inversely during the crisis decade. As turnover fell due to falling demand, which even affected the supermarket industry, a sector where costs are highly inelastic, the market share held by the top 10 retailers increased.

So, if in 2009 the turnover of supermarkets reached 13.14 billion euros, and the market share of the 10 largest companies in the sector was 68.6% (data from NielsenIQ), then in 2016, when the turnover fell to 10.81 billion euros, the market share of 10 the largest retailers increased by about ten percentage points, up 78%. When turnover in 2022 returned to pre-crisis levels – due to inflation, of course – to 13.50 billion euros, the market share of the 10 largest retailers was at its highest level – 82.3%.

The financial crisis caused, and in other cases hastened, the development that was inevitable in the supermarket industry anyway. During this period, two large supermarket chains went bankrupt (Marinopoulos and Atlantic), one went under the control of another to avoid being bought out (Veropoulos), and two multinational chains left the Greek market (Carrefour and Aldi). . . . At the same time, many smaller chains have changed hands under the control of larger chains, a trend that continues today, resulting in widespread concentration in the supermarket category.

The numbers are telling: according to the special issue of Panorama of Greek Supermarkets (published by Boussias), if in 2008 there were 96 supermarket chains operating in the Greek market, in 2021 almost half remained (50). Following the acquisitions in 2022, the number of chains is estimated to have dropped even further, by about five, noting that two local chains were already announced in 2023 (Katerina Market ANEDHK Kritikos and AS Agora from “Sklavenitis”) and is expected to continue.

The pandemic crisis may have resulted in supermarkets, unlike the rest of the retail sub-sectors, achieving larger overall turnover, with benefits not being the same for everyone, resulting in a re-emergence of ‘winners’ and ‘losers’. “, rather than the general opinion that everyone won. The chains that had the most supermarkets, such as Sklavenitis, and therefore could serve more people, when there were limits based on square meters of each store, won. Chains, those who also had a quick response to the work of online stores also benefited, as did those that responded to timely home delivery.

In the first two years of the pandemic, which is no longer considered a pandemic since yesterday, the problems of small chains could be masked by the fact that household spending was directed much more than in previous years to food and grocery purchases in general. However, the exodus of consumers from home, and then the inflationary crisis, which made the large backbone networks more competitive with the supply and variety of private label products, highlighted the competitive disadvantages of small and small and medium-sized chains. .

On the other hand, the need of large companies to expand their presence in many areas, both tourism and non-tourism, as well as to increase their market share, underlies the constant concentration that takes place in the supermarket category.

Launch of e-commerce

In 2015, when capital controls were introduced, the turnover of companies from e-sales, according to the Hellenic Statistical Office (ELSTAT), amounted to 1.80 billion euros and was even considered an increase compared to previous years, precisely because the absence of restrictions on electronic transactions . In the following years, e-commerce may have registered growth, but no one imagined that the turnover of businesses from e-sales would increase tenfold in just seven years. Of course, no one imagined that we would face a pandemic in 2020 and that physical retail stores would be closed for months. Thus, according to ELSTAT, the turnover of enterprises that came from the electronic channel (either through the website or through the application) amounted to 20.46 billion euros. In fact, while brick-and-mortar stores were open in 2022, online sales increased by around 54.5% compared to 2021. At the very least, e-commerce is the new normal for retail, as the boom in turnover doesn’t seem to be temporary, and now this way of shopping has even made its way into the supermarket sector, with consumers trusting online stores even when shopping for fresh produce (fruit, vegetables, fish and meat).

With the opening of physical stores, as well as the rapid development of new technologies in retail, attempts are being made to so-called “figital” (from a combination of physical and digital), the actual use of new technologies to provide services. in the natural world through the use of data, artificial intelligence, etc.

In fact, beyond the borders, these technologies are being used even in the most traditional retail sector such as supermarkets, and can include solutions such as digital signage, which, through a simple “scan” with a mobile phone, can provide a consumer with additional information. receive product information and pay for purchases at the same time without going through the checkout, with automatic replenishment of their credit or debit card, electronic shopping guides and autonomous delivery of orders, for example, using drones.

Source: Kathimerini

Lori Barajas is an accomplished journalist, known for her insightful and thought-provoking writing on economy. She currently works as a writer at 247 news reel. With a passion for understanding the economy, Lori’s writing delves deep into the financial issues that matter most, providing readers with a unique perspective on current events.