“No, my friend, no! Don’t even think about raising electricity prices again, people have nothing to eat, they have nothing to pay for.” The warning that opposition leader Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu sent to the Turkish president during the week proved to be futile. A few hours later, the state energy company BOTAS announced another price increase for electricity and natural gas. Growth is clearly inevitable as Turkey covers most of its needs through energy imports and is therefore, like most of the planet, prone to an energy crisis.

Volatile energy prices and the surge in commodity prices following the Russian invasion of Ukraine have exacerbated one of the innate pathologies of the Turkish economy: its large deficit and consequent dependence on foreign capital to cover it. Turkey’s current account deficit in the first half of the year was $32.4 billion, according to the latest data. A large increase in the current account deficit was, after all, why Moody’s downgraded Turkey’s debt rating to junk bonds last month, and Standard & Poor’s and Fitch are expected to do the same. However, as the Al-Monitor website reported this week, only 8% of the deficit was covered by foreign capital inflows through direct or portfolio investment, and 38% by the central bank’s foreign exchange reserves. The remaining 54% of the deficit was covered by the so-called inflow of capital of unknown origin.

Al-Monitor estimates that the funds may, among other things, come from criminal activities.

This is an accounting category that may, to some extent, cover legal foreign exchange flows resulting from the repatriation of foreign exchange in the private sector. However, as Al-Monitor points out, it often includes illicit cash flows from criminal activities that are difficult to ascertain.

In the case of Turkey, what is interesting is that during the 20-year rule of Tayyip Erdogan, its deficits are growing, and with them the percentage of their coverage by capital inflows of unknown origin increases.

The role of tributaries of unknown origin in covering Turkey’s deficit was increased in 2018. This was the year Erdogan succeeded in institutionalizing the presidency with unlimited powers and relegating himself to a kind of monarch of Turkey. The result, of course, was to further discourage foreign investors, who were already troubled by the unorthodox economic theories of the Turkish president and his tactics of systematically intervening in the work of the central bank and in the formulation of monetary policy. Thus, investment capital inflows declined and unknown capital inflows hit a record $22.7 billion. Since then, unknown capital inflows have been the main vehicle for covering the current account deficit, which has reached $98 billion.

The Bank of Turkey alleges that the various flows of unknown origin are mainly export earnings that were held back in accounting and repatriated business capital. Eventually, he took a series of measures to force Turkish companies, mostly exporters, to repatriate the funds they hold abroad in foreign currency. He often pursues this with indirect threats. Speaking at the Istanbul Chamber of Industry at the end of July, central bank governor Sahap Kavcioglu stressed that “Turkish companies are holding undeclared funds abroad that could amount to $500 billion. They have to bring this money here” and convert it.”

All this largely reflects the change in the attitude of investors towards Turkey that has taken place in recent years. In the years since the devastating financial crisis of 2001, which brought Erdogan to power and destroyed the old political order, the Turkish economy has seen strong growth and large deficits. At that time, Turkey was a favorite of foreign investors, who covered its deficit with their capital. In the first decade, the current account deficit did not exceed 5% of GDP, and the largest of them was in 2011, when it approached 9% of GDP, but was covered by 80% of the inflow of direct and portfolio investment, bank deposits and borrowings. Inflows of unknown origin then covered only 16% of the deficit. Everything changed in 2013 in a situation very different from today, but similar only in that the American federal bank, the Federal Reserve, began to raise interest rates on the dollar. Investment funds began to turn to the United States, leaving the countries with developing economies and, first of all, Turkey. Then ended the era when Turkey could easily cover its deficits with foreign capital. And while the climate for Turkey seems to be improving again from time to time and capital inflows are recovering, opening fronts from Syria to the Caucasus and successive episodes of diplomatic tension with Washington are constantly undermining investor confidence. Of course, the decisive factor is the persistent desire of the Turkish President to reduce the cost of money by devaluing the national currency. After the latest rate cut was decided last month, the Bank of Turkey pushed the Turkish lira towards an exchange rate of 18 pounds to the dollar. Just five years ago, a dollar was worth £3.50.

Growth is by leaps and bounds, but the standard of living of the Turks is falling

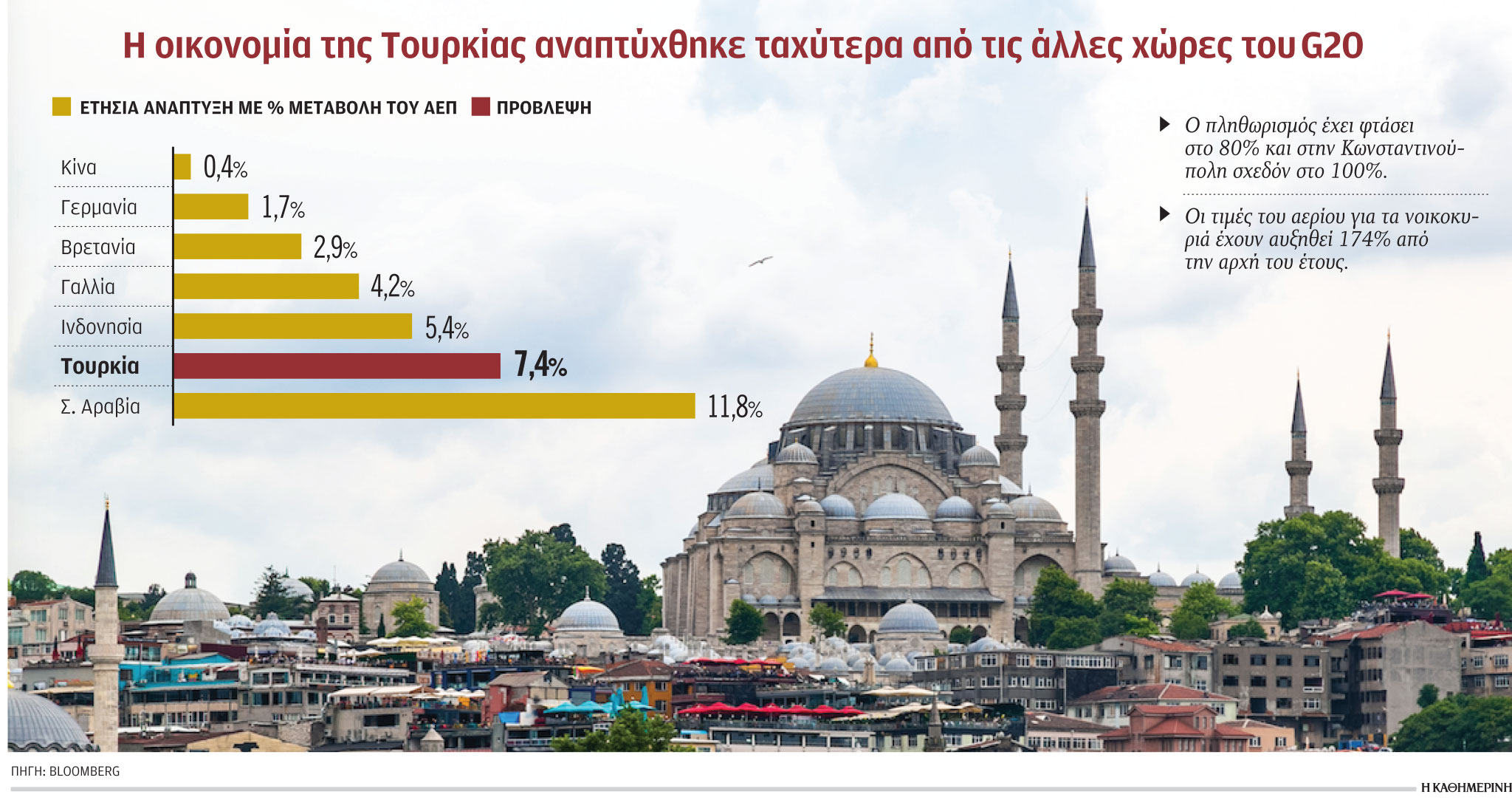

All indications are that the latest increase in energy prices will hit the living standards of Turks, most of whom are struggling to survive as inflation and prices soar, making basic foodstuffs unaffordable. The overall increase in natural gas prices since the beginning of the year for the population is now 174%. And Erdogan’s government is content with raising the minimum wage by 30%, a rate that is quickly dissipating due to high inflation. Adhering to a policy of low interest rates at the behest of the President of Turkey, the Turkish central bank drives inflation to literally a dizzying 80%, which in Istanbul reaches 99.9%. It is noteworthy that a group of independent economists with the initials ENAG, which has repeatedly questioned the accuracy of official figures, now estimates real inflation in Turkey at 176%. These are the economists who were sued when the Bank of Turkey filed a lawsuit against them, alleging that they undermine its credibility. They, however, insist that they use exactly the same methodology that a central bank uses when calculating inflation.

At the same time, however, Erdogan’s government boasts high growth rates, as at a time when recession threatens advanced economies, Turkey’s GDP increased by 7.6% in the second quarter. This is largely due to the recovery of tourism after the lifting of restrictive measures against the pandemic and the growth of tourism revenue by 100%. However, it is obvious that a significant part of the Turkish people does not benefit from such a development of events and does not see what the Turkish president promises from time to time.

Tayyip Erdogan has tried to ‘gild the pill’ of the rapidly depreciating Turkish lira, arguing that it will increase Turkish exports and create jobs, and thus by ‘Chineseizing’ the Turkish economy, he will reverse the deficit. in excess. Something that, of course, is not happening partly because of the negative international situation.

The devaluation of the currency, which has slipped by 27% since the beginning of the year, after falling by 44% during 2021 before it, seems to only bring misery to Turkish households. Last week, the percentage of foreign exchange reserves of banks, which they are required to convert into Turkish lira, increased again.

Reception

In an attempt to justify soaring inflation, Finance Minister Nuredin Nebati emphasized that “as long as we do not risk growing the economy, fighting inflation takes time”, implicitly acknowledging that Erdogan’s low interest rate policy, aimed at growth through cheap borrowing, is to be blamed.

slowdown

Warning the market of an expected slowdown in growth, the central bank noted that the Turkish economy appeared to be “losing some momentum.” With this remark, he accompanied his decision to cut interest rates again, despite unsustainable inflation and a global shift to restrictive policies.

Reactions

“No, my friend, no! Don’t even think about raising electricity prices again,” Turkey’s main opposition figure, Kemal Kilicdaroglu, warned Tayyip Erdogan, reminding him that “people have nothing to eat, nothing to pay for.”

Source: Kathimerini

Lori Barajas is an accomplished journalist, known for her insightful and thought-provoking writing on economy. She currently works as a writer at 247 news reel. With a passion for understanding the economy, Lori’s writing delves deep into the financial issues that matter most, providing readers with a unique perspective on current events.