Almost half of Turks believe the bizarre conspiracy theory that the Lausanne Treaty will expire this July, less than two months after Sunday’s presidential election, and Turkey will be able to return to its Ottoman glory days, The Conversation reports.

Also called the “birth certificate” of modern Turkey, the Treaty of Lausanne, signed on July 24, 1923, was the last of the peace agreements signed at the end of the First World War. The treaty established the Republic of Turkey with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as its first president and largely drew the country’s current borders.

Despite the importance of the moment, this year’s centennial has already generated far more public anticipation than historians might have anticipated, for a less common reason: widespread belief in conspiracy theories.

According to polls conducted earlier this year, 48% of the Turkish population, including 43% of university graduates, believe that the 1923 treaty will expire on the 100th anniversary of its signing and that the document’s so-called “secret provisions” will finally be revealed.

Which confirms the theory about the “liberation” of Turkey

For those who believe in this theory, the “expiration” of the treaty will free Turkey from Western control, and after a century of keeping the “secret clauses,” the country will finally be able to tap into its oil-rich resources. and boron

They believe that once Turkey is freed from the “straightjacket” represented by the treaty, it will once again become a superpower, as it was during the heyday of the Ottoman Empire.

Obviously, none of these statements has any historical reality. But where do they come from? And more importantly, what convinces so many people to believe in them?

Research shows that conspiracy theories are the result of predictable psychological factors. Among these are the motivation to reinforce a strong group identity and the desire to protect one’s group from an outgroup consisting of people perceived as hostile.

The origin of the conspiracy theories associated with the Treaty of Lausanne confirms this.

As historian Gokhan Chetinsaya notes, this can be traced back to the anti-Semitic and nationalist-Islamic writings of figures such as Chevat Rifat Atilhan (1892-1967), the notorious pro-Nazi writer and politician, and Nechip Fazil Kisakurek (1904-1967). 1983), poet and inspiration of the President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

In the 1950s, Atilhan and Kisakurek argued that the Treaty of Lausanne was the result of a Jewish conspiracy masterminded by the former chief rabbi of the Ottoman Empire, Haim Nahum, who was part of the Turkish delegation in Switzerland under the guise of a consultant.

According to both and others who followed them, the 1923 treaty was a great defeat for Turkey, but not only because of the territorial and economic losses caused by its famous clauses and supposedly “secret” articles.

They argue that while paving the way for the abolition of the Ottoman Caliphate in March 1924, the treaty also weakened Turkish society morally, causing serious damage to the “unity and conscience of Islam”.

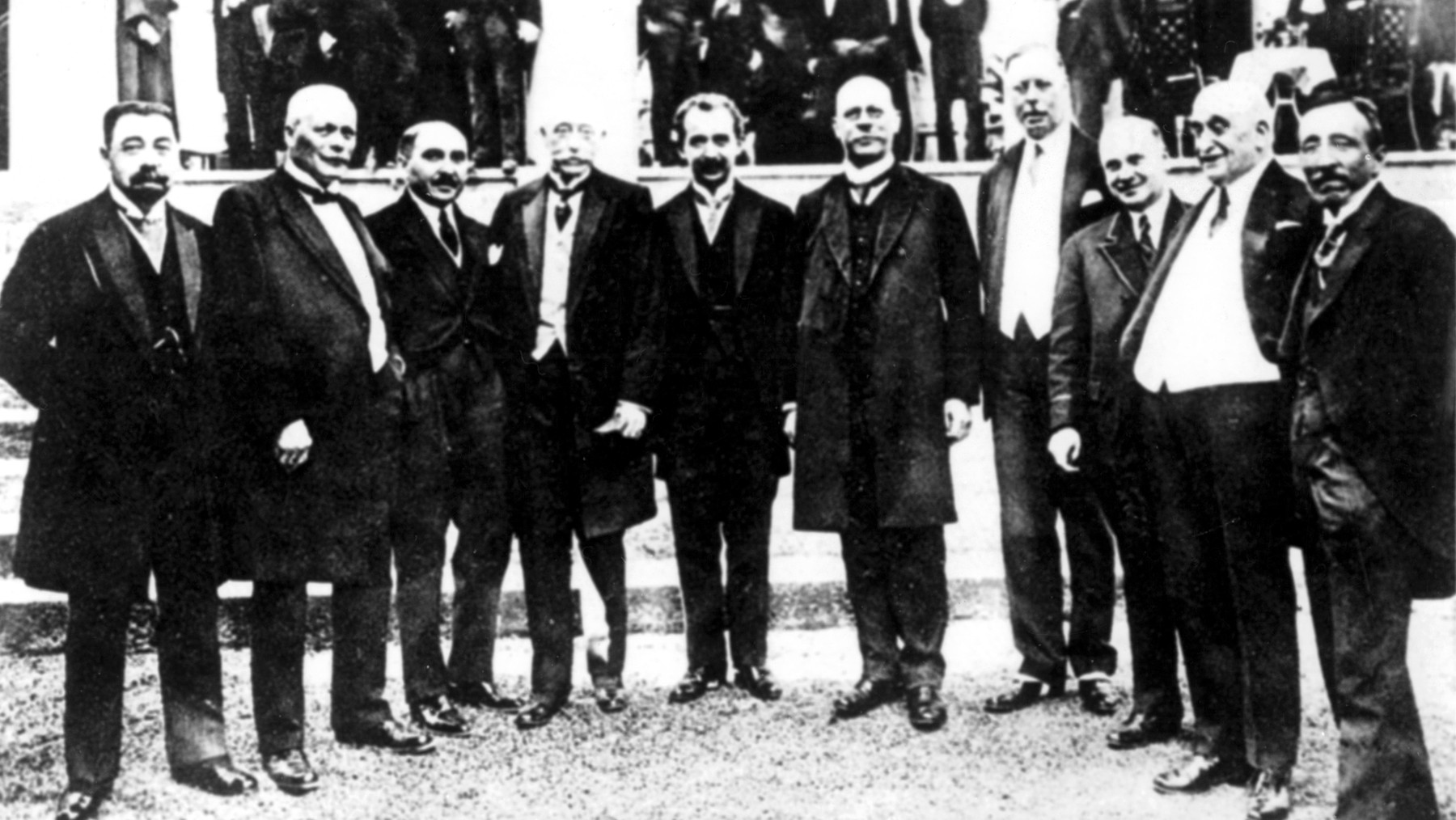

The conclusion of the Treaty of Lausanne ended the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922) (PHOTO: CostFoto / Profimedia Images)

Why conspiracy theories are successful in Turkey and in general

But conspiracy theories about the treaty are not only the result of indifference to historical realities or the way history is taught in Turkish schools, which discourages critical thinking. There are also structural factors.

Social psychology teaches us that conspiracy theories become widespread during times of social crisis, which is not lacking in Turkey.

It is not only the economic and political conditions (according to some, a dictatorship) in which Turkey is now. Rather, it is a lingering syndrome that the country has suffered from for the past several centuries, a syndrome that has left Turkey, and before it the Ottoman Empire, dangerously vulnerable to even some of the wildest conspiracy theories.

Especially after Russia invaded and then annexed Crimea, an Ottoman province at that time, in 1783, an era of paranoia began in the history of Turkey.

It became obvious that the Ottoman Empire could no longer match the military and technological power of its rivals from the Romanov dynasty, which ruled Russia, not to mention other major European powers. This relative weakness eventually led to what would become known as the “Eastern Question.”

Divide this “semi-civilized eastern empire” or remain intact? Should European nations fight over the spoils or negotiate a deal to share it among themselves?

The Ottoman Empire has not understood much since the period of its decline

From the Ottoman Empire’s point of view, the “Eastern question” indicated an ongoing paradox: their empire’s existence depended on the support of the very European powers that posed the greatest threat to its territorial integrity.

For example, in the early 1790s, Sultan Selim III tried to counter the Russian threat by recapturing Crimea with the support of France. However, to his disappointment, this decade ended with Napoleon’s invasion of Ottoman Egypt. An alliance was formed between the Sultan, Great Britain and the enemy of the Ottoman Empire, Russia.

But then, just after Anglo-Ottoman forces drove the French out of Egypt in 1801, the Sultan had to rely on Napoleon’s support to end the British occupation of Alexandria.

Over the next century, Istanbul received numerous reports of plans (many of them) by one or another European power (usually Russia, France, or both) to divide the sultan’s empire.

This is one of the reasons why in 1821, when the Greek Revolution began, the Ottoman authorities mistakenly believed that it was part of a larger Russian plot to invade Istanbul.

They did not understand the national liberation aspirations of either the Greeks or the Lebanese a few years later, nor the aspirations of the Armenians starting in the 1860s, etc. The Ottomans brutally repressed the aspirations of the peoples under their rule, considering them to be foreign vassals of their imperial power, just as republican Turkey is doing to the Kurds today.

Kemal Kilicdaroglu, Erdoğan’s opponent in the presidential elections, is running under the banner of Atatürk (PHOTO: Pavlo Bednyakov / Sputnik / Profimedia)

The memory of former glory haunts Turkey on the eve of the presidential elections

The inclusion of secrecy clauses in Ottoman-European agreements was not an uncommon practice during this tumultuous period of Ottoman decline, so conspiracy theories became a defining feature of Turkish political culture.

The 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, concluded immediately after the First World War, turned the worst fears of the Turks into reality, leaving them in a hollow state centered in Anatolia, while the victorious powers divided up the provinces of their former empire.

But the Lausanne War, launched after a bloody war against Greece to reclaim the western part of the country, changed the situation, leading to the incorporation of some of the lost territories into the new Turkish Republic.

Since then, secular nationalists known as “Kemalists” (the true descendants of former president Mustafa Kemal Atatürk) have seen the Treaty of Lausanne as a great victory, while Islamists have presented it in diametrically opposed terms, often invoking conspiracy theories to further its cause.

Inside Turkey, however, Kemalists and Islamists share a common belief: that a “great conspiracy against the Turkish nation” was prepared by foreign powers – a quote from Atatürk often repeated by the current president, Recep Erdogan.

A century after the Lausanne Treaty, the “Eastern Question” may seem like long-buried history. But the ghosts of the syndrome it once created and the conspiracy theories it left behind continue to haunt Turkey in the 21st century.

I hope you enjoyed this weekend’s Nerd Alert, which took you through a twisty story. If you’re also interested in reading last week’s column, you can find it here:

- “Family Guy” caused outrage in Russia / The next Inspector Clouseau may be African-American / YouTube is again playing with ads

Source: Hot News

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.