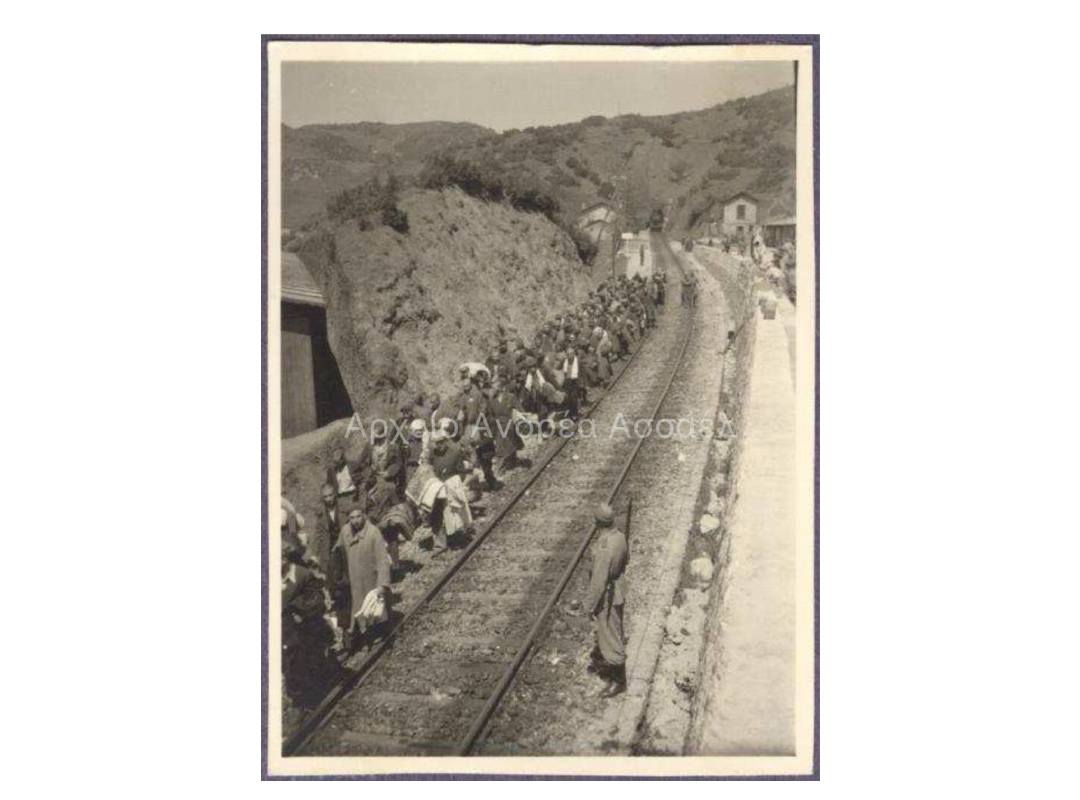

Decades later, they could only search for fragments of history. In late March, German explorers combed the slopes in an unholy corner of Phthiotis with special radars, magnetometers and drones. They were at the scene of the crime, not far from the decommissioned Karja railway station. It was based on a rare photographic document from 1943 and several survivor accounts available.

Even though the landscape had changed due to overgrown weeds and constant looting tore off the rails, there was one sign they couldn’t ignore. There was a 20-meter hill in front of them. Cut in half, it forms a large “V”. It was dug up with shovels, pitchforks and hands by hundreds of Jews of Thessaloniki during Nazi forced labor in the summer of 1943.

A team from the University of Osnabrück recorded and captured the entire area on video and photographs to then assemble their 3D models. But he needed to investigate something else, evidence of the possible existence of a mass grave in a wider area.

It was April 2002, when an electrical engineer, a graduate of the Technical University of Munich and a history buff Andreas Assael found an album with photographs of the German organization Todt in the antiques market in Munich, which commissioned German companies to develop technical works in the occupied territories of the country. “It was a thick dossier. It began with a map of Greece, followed by 400 photographs of the work. A German engineer took them out to document his work for the company,” Mr. Assael, who collects photographs from the occupation, tells K.

In one of these images, he managed to make out the figure of a worker with a star on his lapel. Above the photograph was the inscription: “Karya, the workers are coming.” He bought the album and over the next few years did his own painstaking research to piece together the story. His family in Thessaloniki was one of the few who escaped with the help of their Christian fellow citizens and was not sent to the Nazi death camps.

According to Mr. Assael, he first managed to find one of the survivors of the Carya massacre, Sam Namia, and show him the photographs. “He was lucky because when he was badly wounded in the leg, the master spared him and sent him to the hospital instead of killing him on the spot,” he says. “The work was carried out in terrible conditions, day and night, with dynamite, gunpowder and executions. During the day they were given little water, and for food – a moldy piece of bread and cabbage soup. It is called the worst construction site. Few managed to escape, because it was a very inaccessible place, in the wilderness. The Germans fortified the mountain with machine guns, fearing the rebels, and the only entrance and exit were two tunnels, between which is the Karja station. But these have survived.

Of the 400 photographs that Mr. Assael found, 80 are from the war in Karya. The album does not show the completion of the section on the mountain and closes with tourist photos of Athens. Mr. Assael tracked down other Kariya fugitives in Israel and the US, collected and recorded their stories, spoke to a post-war station guard who witnessed it as a child, and from other sources.

In recent years, this material has been used by a diverse group of researchers who will be on display in Germany and Greece in 2024. The project is carried out by the Memorial Foundation for the Murdered Jews of Europe and the Topography of Terror Foundation, based in Germany, in cooperation with the University of Osnabrück and with the support of other organizations such as the Jewish Museum of Greece in Athens and the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki.

Mr. Assael has written a book about Karya, which is expected to be published when the related exhibition takes place. He also points out that he recently found documents showing which company and which persons from Germany undertook the development of the Kariya railway project.

“The work was carried out in terrible conditions, day and night, with dynamite, gunpowder and executions. It is called the worst construction site. Few managed to escape.”

Historian Jasonas Chandrinos, who is involved in the project as a researcher at the Nazi Forced Labor Documentation Center in Berlin, explains to K that the exploitation of Greek Jews in forced labor is divided into two stages. The first begins on Black Saturday, July 11, 1942, when the men of the Jewish community gather in Eleftheria Square in Thessaloniki. They are publicly humiliated, recorded and sent to prison. They are working on various projects, mainly road construction in Northern Greece. The Jewish community pays a ransom to officer Max Merten for the release of its members, and in March 1943 the first routes to Auschwitz follow. In the same month, the second stage of forced labor begins.

In southern Greece, the occupying forces are in dire need of workers, they want to restore the railway network and increase its efficiency, as it is often the object of sabotage and attacks by the rebels. Mr. Chandrinos says the main construction sites that have been identified were at Lianoklady, at the Asopos bridge, blown up by British commandos in the summer of 1943, at Thebes and at Karya. Not only Jews worked everywhere. Christians were also brought to some construction sites, while at others, according to historical research, Yugoslav military personnel were even taken prisoner.

“They forced them to do something very difficult and with little chance of success, so they only used Jews,” Mr. Chandrinos says of Karya, where about 300 Jews from Thessaloniki were sent. The first group was sent at the end of March 1943, and the second one a month later.

“There was a station there, and they wanted to add a second, parallel, bypass line. They had to clear a hole in the hill to lay the line. The earthworks were done with primitive tools, shovels, picks and primitive compressors,” says Mr. Chandrinos. “The project was completed in August. Some of the workers, who could still move and looked like people, were sent to Thessaloniki,” Mr. Assael notes, adding that according to the testimony of the rest, they were shot and placed in a mass grave, which has not yet been found. In August 1943, the last train for Auschwitz leaves Thessaloniki, a train of forced laborers.

A team of researchers from the University of Osnabrück checked out various sites in the area, which locals have also suggested as possible mass grave sites. Historian Christoph Ras, a professor at a German university, told K that they were unable to find relevant evidence on these sites. “We are sure that people died or died during the work and were definitely buried somewhere. We think they are not in the places they showed us, the area is complex and big and has changed over the years. This means that the executions probably took place elsewhere, or that the survivors were sent to German camps and killed there.” Researchers have not excavated in the area, as Jewish religious tradition forbids the exhumation of the dead.

Russ’s group in the field was followed by the historian Valentin Schneider, who records in a database all the German military and paramilitary units stationed in Greece, a project he is running at the Institute for Historical Research of the National Research Foundation with financial support from the German Embassy. Mr. Schneider is now searching the German archives for evidence or reports of what happened at Karja Station. “The railway was the only artery for the maintenance of troops in southern Greece,” he emphasizes. “They wanted to control the line for the extraction of raw materials from Greece, for the transport of troops and ammunition,” adds Mr. Assael.

The work of the Osnabrück explorers was difficult. As Mr. Russ explains, they had to travel back in time and find out which elements were built in 1943 because the station continued to operate after the war. A button, shells and other small items dating back to the period in question were found at the site where the huts were located, in which the workers were accommodated.

“As a historian, I want to honor the memory of the victims, to make sure that they are not forgotten. It’s important to tell their stories,” says Mr. Rush. “At the same time, we remind German society and the world of the crimes committed by my country during the Second World War. Part of the Holocaust was not only deportation to concentration camps, but also forced labor.”

Mr. Chandrinos emphasizes that, until recently, the phenomenon of forced labor was not among the priorities of collective memory, both in Greece and in Europe. He also points out that there are at least six fully identified accounts (based on more than one source) of what happened at Carya. Some of the few survivors have been interviewed in an audiovisual archive produced by Steven Spielberg’s Shoah Foundation, and investigators are awaiting material from the US.

One of the workers who managed to escape was Isaac Mois Cuenca. At the beginning of 1944, he was arrested in a block in Athens and taken to Auschwitz, from where he survived. In 1954, he wrote in Spanish-Jewish Ladino: “Karya was hell on earth.”

Stations

1943

March

At the end of the month, the first Jewish forced laborers are sent from Thessaloniki to the Karya Phthiotis railway station.

August

They are completing their project – a cut in the rock for laying a railway line. For months they worked in extremely unfavorable conditions, with little water and food.

2002

April

Andreas Assael finds an album in Munich with photographs of Nazi power work in Greece. Included are images of Karya. He begins a multi-year investigation, finds survivors, collects evidence.

2023

March, April

An interdisciplinary team of experts from the University of Osnabrück in Germany is conducting research in Kariya, also examining possible locations where, based on the evidence, the mass grave was located.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.