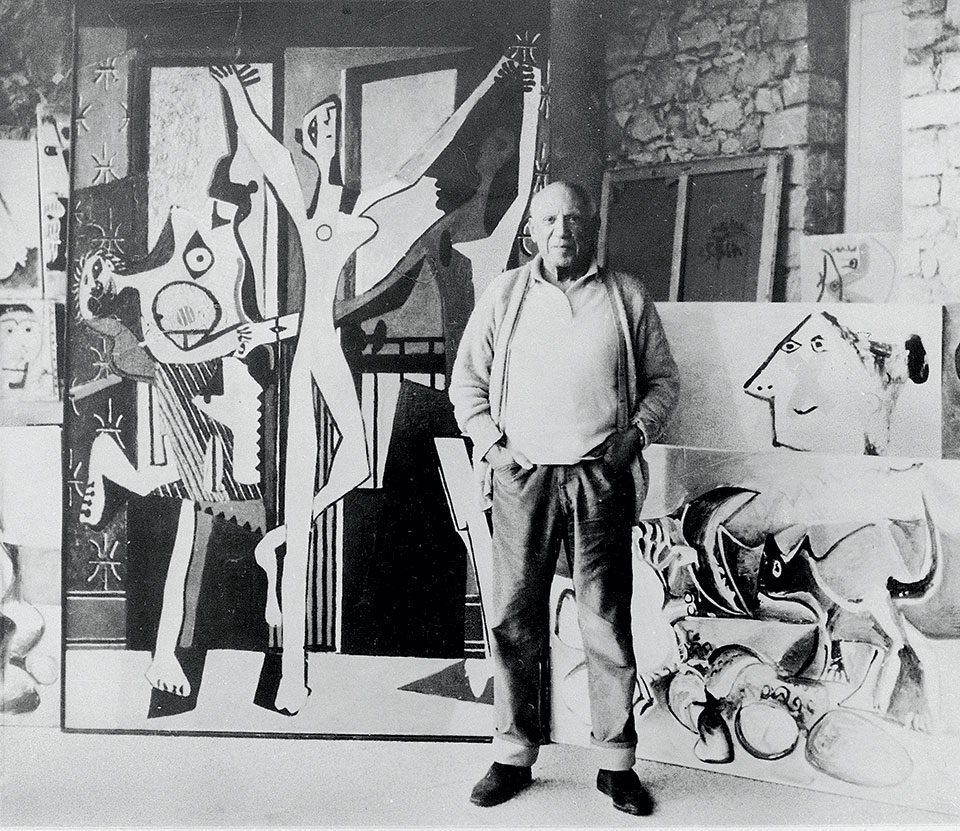

Last Saturday marked the 50th anniversary of his death. Pablo Picasso at the age of 91 and until now, perhaps no other creator has come to such a degree of identifying his name with his art: even if you ask a child what great painter he knows, he probably will not think of anyone else.

Picasso himself, the innovative and unimaginably prolific Picasso who left an indelible mark on 20th-century art (and beyond), might appreciate such a compliment: he reportedly once said that although it took him only four years to reach the level of Raphael , it took him a lifetime to learn how to draw like a child. If there is anything like self-confidence in the above statement regarding the Renaissance artist, it is because Picasso, by all accounts, was anything but a moderate person. Much has also been written about how he treated his female companions: The Guardian recently questioned whether the artist should be taking the “treatment” of withdrawal culture.

However, his artistic work, his radical and multifaceted character, is hardly disputed, even with accusations of cultural appropriation attributed to him. Many important Picasso exhibitions are organized this year in Madrid, Paris and New York.

Of great importance is a more personal attitude to it, a more individual look at the work and its imprint. They show that such a size as Picasso’s, such a large displacement, can be transformed into something unimaginable and earthy at the same time. And so, a little more accessible.

I would divide artists into those you love for their sensitivity of expression and those you love for their ability to formulate indelible, archetypal images that evoke emotions and remain deeply remembered. Picasso belongs to the second category. You approach him not for his beauty and lyricism, but for his ability to reshape reality so that the viewer can get a wider perception of it. I first heard his name when I was a child, in the countryside, and my grandfather was impressed by the newspaper articles about his death. Before taking the art exam, I read his biography of Timothy Hilton – his life impressed me. Later I came to the conclusion that his most important period was the period of analytical cubism, and when I saw “Miss Avignon”, I realized what a turning point in the development of modern art. The artist cannot leave him unnoticed.

I always tell stories that connect Picasso with the Russian avant-garde. Lyubov Popova and Nadezhda Udaltsova went to Paris to meet him. Vladimir Tatlin infiltrated his studio under the guise of a street musician looking for work to spy on his new projects. But above all, Picasso’s iconic painting The Avignon Mrs. served as a paradoxical occasion for the invention of a new rule in Russian poetry: the rule of “displacement”. The deliberate distortion of the generally accepted aesthetic balance in “typographical”, “optical” or “syntactic displacements” was characterized by the futurist poet Alexei Krutsonih as a continuation of Picasso’s pictorial innovation in futuristic poetry. I doubt that Picasso ever studied.

Picasso’s “Miss Avignon” radically defines postmodern consciousness, revealing in subversive language what will mark the age of world wars until today. The ladies of the brothel in the Rue Avignon, the female knights of the Apocalypse, present us with a barbaric omen of what is to come in history. The paranoia of the new, industrial age, the arrogance of the new individualism, the crisis of humanitarian values, the consciousness of the fragmentation of identity are fixed as a disharmonious image of an existential impasse, from where it can theoretically be deduced: in the space of love. For the political Picasso, the driving force of history is critical consciousness, uncompromising spirit. “We must make a revolution against the common mind,” he writes. With “Guernica”, he mercilessly attacks this mind, which, with its criminal tolerance, led to the horrors of the Second World War. Art, he says, seems to be connected. What matters is which side you are on. After all, who made “Guernica”? Picasso or German airplanes and reassured hypocritical bourgeois of the 20th century?

Picasso entered the life of my generation from a thousand sides! Modern trends dynamically meet in his work. His personality embodies the ideological attitudes and feelings of a progressive person. The determination of the artistic act complements the thrill of the immediacy of his work (I rarely wept in front of a painting, in Guernica). His ingenuity and experimentation, his clarity and dynamism of writing embody the best that modernity has to offer and reinforce the modern perception of the work of art. The frankly romantic element, the revolutionary power of gesture, the inner calmness and relaxation in his works merge with life. It is hardly possible to think of art as a renewal of speech, as an expression of human sensibility, and as participation in history without its presence. Picasso is the key that opens all the doors of the twentieth century.

My Picasso is gone. If there is an artist that I consider my own with the importance of weaving, it is Matisse and Triantafillidis. I address them inconsolably. But I have an infinite, unspoken respect for Picasso. Picasso, who at sixteen painted like Raphael, Picasso, who never in the history of art was such an artist, sculptor, ceramist as he was. Who set the standard for contemporary art, but when Kahnweiler told him to “leave Cubism for a while and do something neoclassical,” he created figures that Michelangelo and Ingres would envy. I admire Picasso.

I will never forget the thrill of admiration that I experienced before the youthful work of Picasso in the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. Wandering through his rooms, I could not stop admiring them with joy and fullness: it is this collection that contains intense experiments and promises, due to the young age of the artist. Recently, the Museum of Cycladic Art hosted a periodical exhibition where Picasso’s work was displayed alongside masterpieces from Greek antiquity. It was one of the most important presentations, because reading the raison d’être of art, which generously offered its soul, gave the atmosphere a timeless character and a human transcendence. There, after 2500 years, it was difficult to separate them.

Oddly enough, the Baltis painting has been etched in my memory ever since I visited the Picasso Museum in Paris. But there I saw – and was moved by – Still Life with a Straw Chair (1912), a landmark work in the history of collage. I really like his erotica, presented at the exhibition “Picasso érotique” (2001-02). Picasso managed to become a big star and therefore constantly appears in front of you. Last month I met him in Ethel Adnan’s book On Cities and Women, where she describes, among other things, her visit to the Picasso Museum in Barcelona. And while I was studying the art of the late 19th century, I came across the amazing realist work “Science and Charity”, which he wrote in 1897. He was only 16 years old.

During my first student trip to Rome, I bought a book, a Picasso retrospective published by Rizzoli. I highlighted a 1901 self-portrait in a black coat. Extremely simple work, it relieves a serious face like an off-white blur against a dark background. This picture, pinned to the wall of my laboratory, accompanied me during my student years. Clippings from drawings and projects that run through almost his entire career, I came across many times in the workshops of friends. A unique experience, especially for those years, the sharpness of his gaze. An exuberant pioneer, a personality overflowing with passion and vitality on the path of 20th century art.

I was 7-8 years old when we bought the curtains and the seller insistently urged us to buy a Picasso painting. Then, hiding behind these curtains, I tried to decipher the plan. Later I found him in a magazine, posing, looking into the lens with fake, deformed clay fingers, and then I was convinced that this creature must have such strange hands to draw these strange pictures. I adored him. It was the first painting I discovered in the Louvre at the age of 17. These were the works of “my” artist! Mysterious, strange, complex, with 5-6 careers, or even more, he made the image as he wanted. He treated her as if he were his mistress, and always in Portrait of a Weeping Woman I saw how the picture itself mourns his death bitterly.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.