Each of us has an image of Alexander the Great. We usually imagine him as a warrior on horseback with a spear in his hand, galloping fearlessly on Bucephalus, who conquered one country after another. None of us, however, could ever imagine him as another Captain Nemo, stuck inside a glass diving bell, where only a rooster tells the time and a cat disinfects the air (as they then believed), exploring not the depths of the East, but the sea. And yet that is how a naive but infinitely good French illustrated manuscript with stories from his life, dating back 600 years, presents him as such.

The visitor to this fascinating exhibition must be open-minded and let their imagination run wild. But most of all he must love fairy tales. What he will see is very different from what he knew so far. Because the subject of this unique exhibition is not so much the historical personality of Alexander the Great, but the influence and influence of myths and narratives about his life in the field of fiction. “Until now, no exhibition has explored this rich heritage,” confirms Dr. Peter Toth, exhibition curator and head of the British Library’s Ancient and Medieval Manuscripts Department. Through many medieval manuscripts with exotic drawings, the visitor will see the unexpected faces of Alexander the Great, created in his image and likeness by different peoples and different eras.

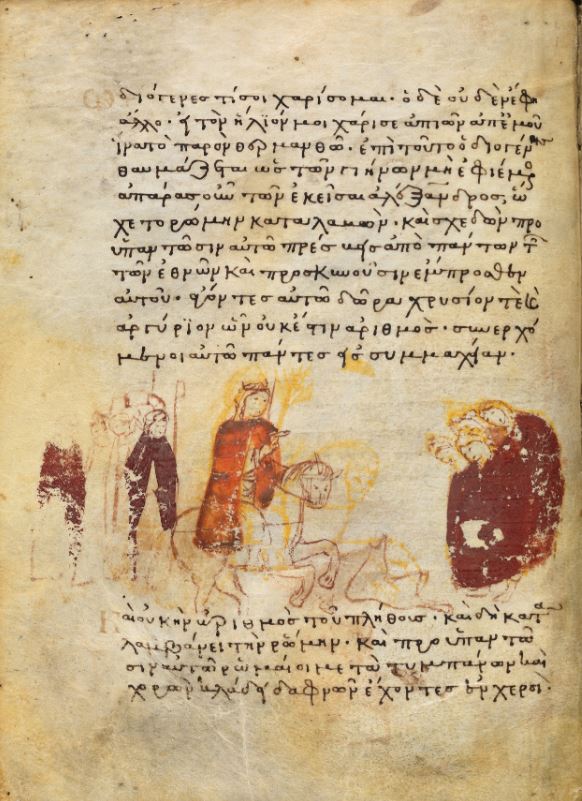

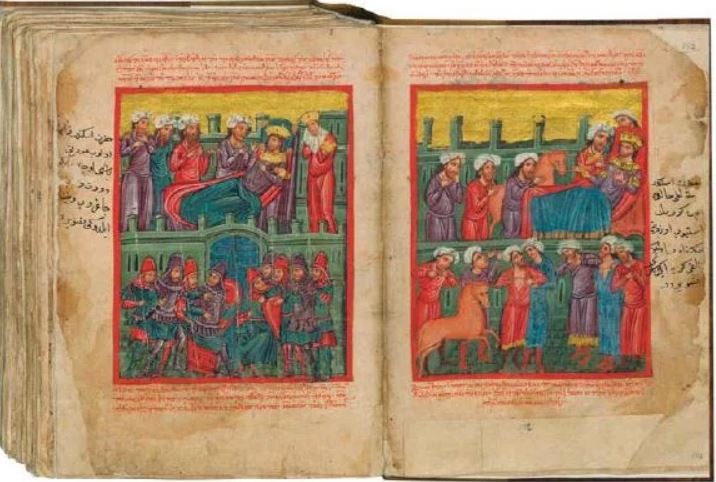

For example, a 14th-century manuscript from Britain containing stories in Latin depicts Alexander the Great as a medieval king with curly hair and a crown on his head. In another 13th century, written in Greek, the Macedonian king is depicted entering Rome on a donkey, like Jesus in Jerusalem, on Palm Sunday, and crowds greet him with palm leaves in their hands. In a 15th-century German manuscript, the great warrior is dressed as a Byzantine emperor with two tusks protruding from his jaw.

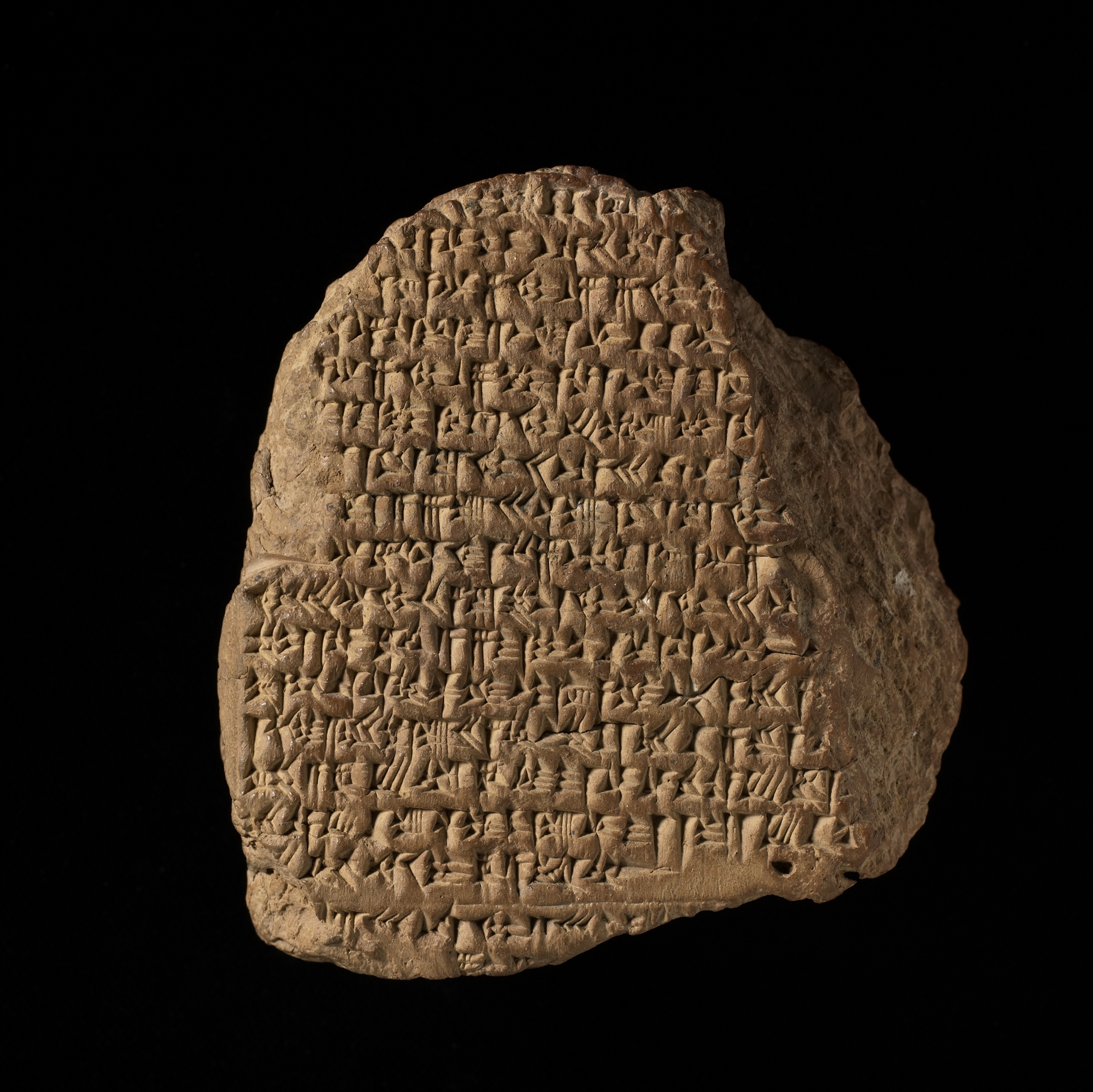

The historical figure may have reached northwest India, but the mythical explorer of land, seas and sky (in one painting he is shown in a hot air balloon pulled by griffins) seems to have conquered the universe. However, there are also several historical sources in this fantasy world that permeates the exhibition, such as, for example, a Babylonian inscription that mentions the victory of the Macedonian king over Darius in Gaugamela (present-day Kurdistan) in 331 BC. . or 2,200-year-old papyrus fragments containing texts describing strange lands visited by Alexander the Great with his troops. These historical documents form the basis on which myriad new fictional stories about the popular man are artfully constructed and embroidered to this day.

The video shows how the narrator is still talking about the adventures of Alexander the Great in the coffee houses of Iran.

Oral stories about Alexander the Great have existed for centuries – even as long as he was alive, and still exist, judging by the video at the end of the exhibition, in which the narrator still talks about the adventures of Alexander the Great in the coffee houses of Iran. These accounts were originally written in Greek, possibly in Alexandria, around the 2nd or 3rd century AD. And each time they were written or copied, new elements were inserted or others omitted so that the stories could be adapted to the needs of readers. Over time, these stories were so successful that they were translated into many languages: Coptic, Arabic, Persian, Latin … They spread throughout Europe and Asia, acquiring their own essence. They became bestsellers. And like any bestseller that manages to stimulate the reader’s imagination – check out J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter books – there was no shortage of stories and descriptions of monsters, giants, cannibals, wild men with one eye or face on their chests, griffins. , dragons, sirens, trees that gave prophecies…

“But with the Renaissance came the end of their success,” says Dr. Toth, “for the first time, scientists set out to dig up the “real” Alexander from the “garbage” of medieval tales, as they called them.” , and focused on “historical” sources such as Plutarch, Arrian, and others, to discover the true man and appreciate his greatness. After this breakdown, they coined the term “Alexander Romance”, which was a chest in which they kept all the novels and fairy tales that they considered unworthy of scientific study.

And who has not appropriated Alexander the Great for himself by means of these mythical stories! In Egypt, it was believed that his father was not Philip II, but Nectaneb, the dethroned pharaoh who seduced Philip II’s wife Olympias into sleeping with him, taking the form of the horned god Amun. Thus, being “his own”, Alexander the Great was the rightful heir to the throne. The same is true in Persia. Alexander the Great was considered the half-brother of Darius, which meant that the Persians were not defeated, in their eyes Alexander the Great was not a conqueror, but a rightful successor. According to the Persian version, Nahid, the daughter of King Philip II, married the Persian king for diplomatic reasons, but because she had bad breath, the king expelled her and sent her back to Greece, where she gave birth to Alexander the Great. In another story, we learn that the grandfather of Alexander the Great was an Albanian, the hero Florimon, who saved the Greek princess Romadanapli from the hands of the evil Hungarian king. They married and their first child was Philip, who became Philip II of Macedon and father of Alexander the Great. Novels give and take.

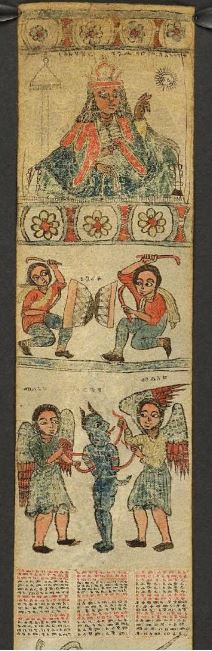

And it was claimed not only by countries, but also by religions. On display is a beautifully illustrated scroll from 18th-century Ethiopia, held up like a kind of talisman depicting Alexander the Great as a Christian leader with magical powers against evil. In Jewish writings, Alexander the Great was circumcised. Zoroastrians in Persia considered him a demon and a destroyer of religion. They all used it in one way or another for their own purposes. And it was used not only by peoples or religions, but also by rulers for whom it was a model. Shiny armor in one of the halls of the exhibition, belonging to Henry Frederick, son of King James I of England, is decorated from head to toe with gilded images of the campaign of Alexander the Great in Asia. Even Rigas Feraios, in his manifesto, in order to raise the Greeks to revolt against the Turks, chose the image of Alexander the Great in a helmet, framed by the faces of his generals with their names and battle scenes.

Exhibits from twenty-five countries, written in twenty-two languages.

Today, the examples of appropriation presented at the exhibition are more of a commercial nature and are related to entertainment and games. In Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck and Scrooge discover the lost sarcophagus of Alexander the Great. While the search for his lost tomb becomes an Assassin’s Creed video game.

His legend continues and continues to mutate to the point where the great conqueror becomes the villain of the story. In one of the comics, Superman fights Alexander the Great, who kidnapped the heads of various states, including Thatcher (!), in an attempt to return the lands that he once conquered.

Is King Alexander alive? “He lives and reigns,” the message says. Who would have thought that Alexander the Great managed to conquer not only the East, but also the literature and cultures of Europe and Asia – judging by the exhibits that arrived from twenty-five different countries and were written in twenty-two different languages. “But why is there such an exhibition now?” I ask Dr. Thoth.

“2023 is widely regarded as the ‘Year of Alexander’, full of events and conferences around the world.”

“The exhibition is timely because it makes us think about our own multicultural and globalized culture, where rumors and stories, oddly enough, often play just as important a role as they did in the time of Alexander the Great, obscuring historical reality and serving various propaganda interests. Also, 2023 coincides with the death of Alexander the Great, which we understood after the creation of the exhibition, but this is not the exact anniversary, because Alexander the Great died 2346 years ago. However, 2023 is widely known as the Year of Alexander, full of events and conferences around the world.”

The exhibition will be open until February 19, 2023.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.