On the day of the fire, the then 22-year-old Krissa Gerakaki was not in Mati. She was in the architectural office where she worked, but was constantly on the phone with her mother, two younger sisters and grandmother, who ran to escape the flames that were threateningly approaching their house. When they got together late at night, everyone was safe, they cried for a while in each other’s arms. They were tears of relief, but also of horror for what they had been through and for what they all knew had happened.

The next morning he found them again in Mati. Their own home where they spent the summer was unharmed, so Khrysa, along with other young people, “children of the fire,” as they call themselves, set to work to help. They went around the neighborhood, distributing water, food, clothes to all the needy neighbors. “We were all frozen. With a blank look. Shocked,” he recalls. In those early days, she herself began to feel something else, but she did not dare to talk about it with anyone. He felt guilty. Not because of what the then government tried to attribute to them, but because she and her family survived while others did not. Their house was intact, while other houses were burned to the ground.

A month later, he left for Germany to receive a master’s degree in architecture. One Sunday, she was invited to a barbecue in the park. And then he suddenly felt that he could not be near the fire. Even the smell made her panic. “I realized that I wasn’t in touch with my feelings about the fire at all. I didn’t want to admit that I was carrying any burden because we were “lucky” to have survived. We were not allowed to get sick,” he explains.

When it came time to decide on the topic of her dissertation, one thought was constantly spinning in her head: can she translate all these emotions that she experienced, her own memories, into a space that includes the responsibility of memory? But the thought of creating a monument in Mati frightened her. He knew it would be a painstaking process, that virtually every day he worked on it, he would relive that day. At the same time, the survivor’s syndrome reappeared at times. “Perhaps someone will think that I, who have not lost any of my own, take advantage of what happened or his pain,” he thought. Until the last day, when she had to present her idea, she hesitated. But that morning, he took a deep breath and sent the proposal to the school.

For the first four months he studied exclusively literature. First, the psychological and sociological part, and then how it is connected with architecture. “After all, how do monuments help? Is memory preferable to oblivion? What is the relationship of architecture to memory, trauma and identity?” – these are some of the questions that worried her. He found that the attitude of architecture towards monuments had changed all over the world. Now these are pieces of public space that do not make you feel anything, but are full of symbolism. Like the bare concrete Holocaust memorial by Peter Eisenman in Berlin, or the simple granite monument with the names of Vietnam veterans engraved in Washington by architect Maya Lin. “Such memorials are important for any painful memory. They open a dialogue with the past and the future. This is the window that connects them, ”says Chris Gerakaki.

“There wasn’t a day that I didn’t cry over projects,” she says of her work at the Bauhaus University.

All this theoretical background was her shield so that she could design her own monument without being carried away only by emotions. Although the feeling was always there. “There hasn’t been a day that I haven’t cried over design. I of course realized that in the process the emptiness I felt at first turned into sadness and then into anger. Came the “why” and questions about what went wrong. So they were integrated into the design as well.”

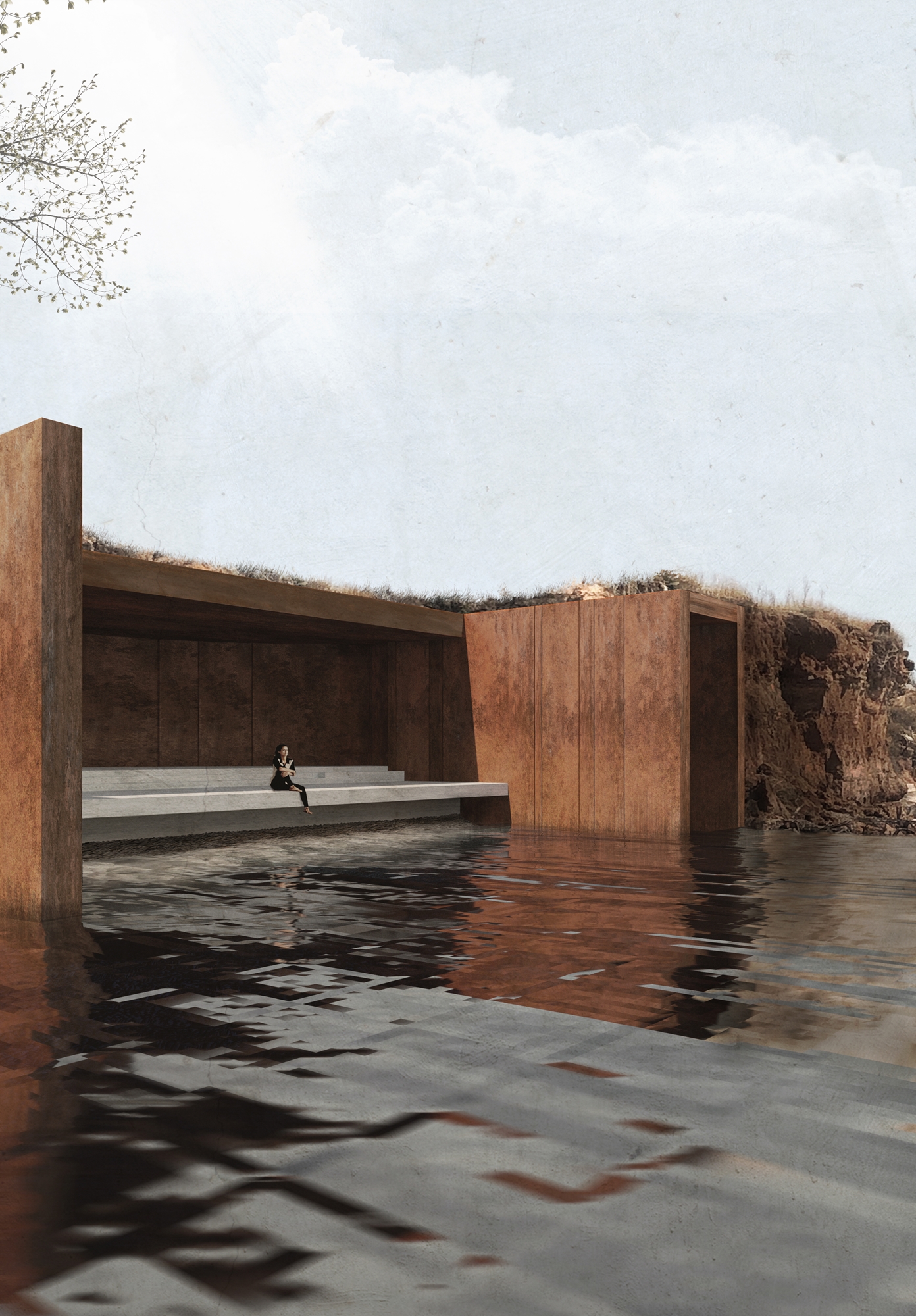

When the day came eight months later to submit her architectural proposal to the Bauhaus University, she was surprisingly no longer anxious or nervous. “I didn’t even care what the professors would say or what grade I would get. This thesis was my own psychotherapy,” he explains. It seemed to her that she herself had passed through one of the monuments he designed: four gardens, symbolizing the stages of fire. A garden of the past, with dense and intense vegetation, similar to the one that existed before July 23rd. The Garden of Fire, a labyrinthine path of seemingly burnt vegetation that symbolizes all the feelings of panic when people didn’t know where to go. A garden of emptiness, with black soil and coal-like stone, symbolizing emptiness and the complete absence of emotions in the first period. And finally, the garden of absence, underground, with 103 empty seats, one for each deceased. However, at the end of this experiential experience, the path leads you outward into the light. There, in the space that embraces you, the gaze is fixed on the horizon. “I think that through the whole process of realizing this architectural concept, I went through these gardens and achieved my own purification. Now I can understand how people go through trauma, so I know where I am, what is happening to me, and what I will have to go through along the way.”

“But no matter how much time passes and no matter how hard we try to heal, our wounds always leave scars. Scars, sometimes ugly or mutilated, but reminding us of what we have been through, ”she writes in the epilogue of her thesis, completed in November 2020. How deep are these scars – wounds – she herself once again confirms in the last quarter, where the trial of the Eye is taking place. Thanks to the testimony, they all relive that day, and now the need for justice to expose the errors, as well as the attempt to cover them up, is more urgent than ever.

The five proposed monumental interventions are scattered across the territory of Mati, autonomous, but also part of a network of memory and symbols associated with the most critical moments of the disaster. She hopes that perhaps one day they will materialize in honor of those who are no longer here, but those who are still struggling with their traumas. As a reminder of a day no one should ever forget.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.