Consider a house that has only individual fixtures. Wires must be laid, an electrical circuit must be created to light the house. American researcher, educator and writer Marian Wolf compares the impact of reading on a child’s brain with this condition.

From birth to age 5, children develop parts—the individual light bulbs in the example above—which then create a “chain.” “These pieces – speech, language network, words, how you use them – kids don’t know the words ‘grammar’ or ‘syntax’ yet, but they build their knowledge of grammar how words work in a sentence.” , he says to “K”. They may not read yet, but through children’s stories, children begin to understand that words make them feel, what another being feels – usually, he says, animals appear in stories – and so a small child, in addition to being familiar with words, begins to form a sense of how emotions work. At the same time, when an adult reads a book, children understand that there are words in the story that remain unchanged on the page, and begin to acquire an initial understanding of letters and the alphabet. “All this happens sooner than in 5 years,” notes Ms. Wolf. However, in the world of digital learning, all of this is under threat.

Let’s get back to the chain. Reading begins when this circuit is established, she says, and helps the brain’s functional connectivity. “Within a few years of creating a brain reading circuit, it goes from a very simple to a much more complex circuit, deepening the ability to comprehend information and content, while it starts to become much more mentally complex and children begin to get in touch with much more complex thoughts. ”, explains Ms. Wolfe. The child begins to understand what he already knows and what is new, as well as what he can understand if you combine new and already existing information, and this is where critical and analytical thinking begins. “I described this process to you for a very important reason,” explains Mrs. Wolf “K”, “because by the age of 10-12 the child builds a very impressive scheme, the more he reads, the more he begins to perceive visual images that do not belong to him, and that makes the child less self-centered.” “So,” he continues, “this reading pattern is extremely important.”

Nevertheless, the scheme is plastic, he emphasizes. It depends on the child’s acquaintance with the knowledge with which he can draw analogies. If children haven’t started building their vocabulary from 0 to 5 and 5 to 10, if they don’t understand how words work, then this schema becomes too superficial and cannot activate more complex thought processes. “We know that education and environment have a very big impact on the schema, but we didn’t realize that the environment in which a child reads affects how the schema works,” says Ms Wolf.

The speech areas of the brain are better activated when someone reads a story to a child than when a child hears or sees it on a device.

Reading, he claims, is a human invention: “the great mistake of teachers and parents is that reading occurs by itself.” At the same time, in the context of human evolution, reading, which is about 6,000 years old, is a recent invention. This means that the reading scheme is very flexible. The environment in which the reading is performed affects how the various parts of the circuit develop. So, we come to the topic of digital learning, mobile phone, tablet and computer screens and their influence on the development of these parts of the child’s brain.

For Marian Wolf, this problem is so serious that she says it is changing the way humanity assimilates, uses and consolidates memory. According to him, research by child neurologists shows that the language areas of the brain are best activated when reading to a child occurs through human interaction, that is, when a person reads a story to a child, and not the child listens or listens. seeing it on some kind of electronic device is between the ages of 0 and 5. One of the reasons has to do with human contact, “so in children, reading is associated with love, tenderness, touch,” she says. Another reason is that reading is interactive. From showing something on the page, helping the child understand the story better, to further explanation, such as “Remember when we saw that animal?” “The child constantly interacts with the person who reads to him, talks to him, sings children’s songs to him, and even this helps in reading later, because the child understands that words have sounds,” Ms Wolf explains.

The screen, according to research, is the worst option for activating these language zones, he notes. “Because it is passive, but constantly diverts the attention of the child, up to its change, and then the child requires hyperstimulation and gets used to the desire to constantly change his attention,” he adds. When you then take the device from the child, he will say that he is bored. “As a child, when you are bored – and you don’t even know what the word means – you go out to do something, imagine, create, play,” says Ms Wolf. But today’s kids are having hours of digital entertainment, and while they are developing digital skills, they are not developing exploratory and creative behaviors. “They still have imagination, it’s important to emphasize that it’s neither, I’m not saying that we shouldn’t have any digital devices at all and should only read books, but the use of screens should be very careful between 0 and 5, and do not teach reading digitally until the child has a sense of the process of deep, analytical reading, ”she emphasizes. Educators, he adds, must learn to teach digital wisdom, how to use digital devices with care, but also for good, to program or code to complement what we read and delve into the subject without constantly diverting our attention, not constantly being on social networks.

We will have superficial citizens

But if kids don’t develop exploratory, creative behaviors like they used to, what are the long-term consequences? “There are many of them and they are different. From childhood, we develop dependence, vulnerability to faith instead of analytical and critical thinking, and this will be an unsuccessful development for our species and for democracy,” emphasizes Marian Wolf. “The problem is that we will have less critical and more superficial thinkers if all they learn is how to swipe across a screen.” Of course, he admits there are many advantages to digital reading: you can find what you’re looking for quickly, or read very quickly. But fluent reading, very fast superficial reading, useful only if you have already developed deep reading ability “Then you can say that I don’t need to go deep here, I can read superficially.”

Young people are distracted about 27 times an hour, switching between different media. It destroys critical thinking.

All this, of course, does not only apply to children. He gives examples of distractions we’ve all experienced, like getting distracted by ads when reading a digital article, or getting text when reading on a mobile phone. “Our youth,” he says, “are distracted about 27 times an hour, switching between different media. It’s an incredible critique destroyer, you don’t have time to activate those parts of the brain that will think deeply.” Another danger, he points out, reiterating that deep reading helps give you time to think about other people’s points of view, concerns echo chambers. “I believe,” he says, “that the divide in my country is fueled by digital devices and social media that, through algorithms, lead people to what they already believe, so the algorithm encourages ignoring the different points of view that are necessary for democracy.” Thus, thinking is not expanded, information is not critically analyzed, you simply accept it, and this leaves you vulnerable to disinformation. That is the danger that we become vulnerable, superficial, prone to thinking. “You’re as smart as ever,” says Mrs. Wolfe to “K,” but you don’t use your mind analytically.

Who is she

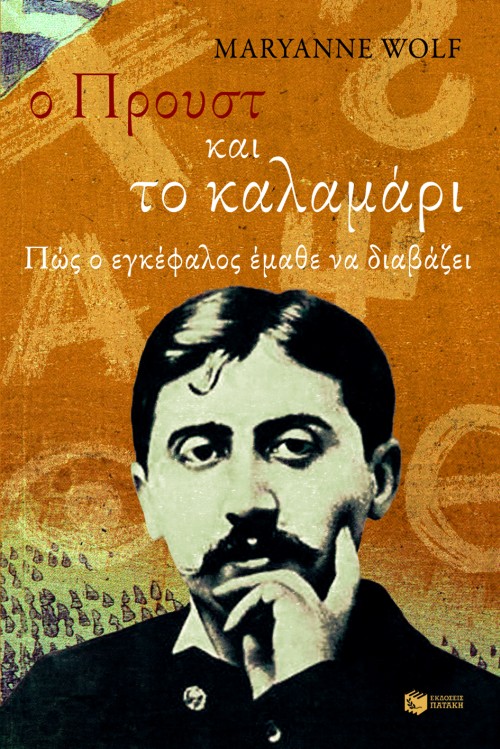

Marian Wolf, director of the Center for Dyslexia, Student Diversity, and Social Justice at the University of California, Los Angeles School of Education and Information Studies, devoted her research to how the brain learns to read. Previously, he directed the Center for Reading and Language Studies at Tufts University and did research at Stanford and Harvard Universities. He has published over 160 publications on reading and dyslexia, and his books include The Reader, Come Home: The Reading Brain in a Digital World, and Proust and the Squid: How the Brain Learned to Read, also published in Greek by Pataki. publications.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.