In the field of music, we would cite Forminx’s “Jeronimo Janka” (1964), which unwittingly inspired the creation of verses like “Janca dances and Anna Maria, Janka dances and the king.” In literature we will find such works as The Lost Spring by Stratis Cirkas, which takes place in Juliana, as well as Casa Biafra by Giorgos Skabardonis, The Greek Doctor by Karolina Mermigas, Xifir Phaler by Athena Kakouris, etc. But what remarkable references and representations did Greek cinema leave for the monarchy, which is so connected with the image?

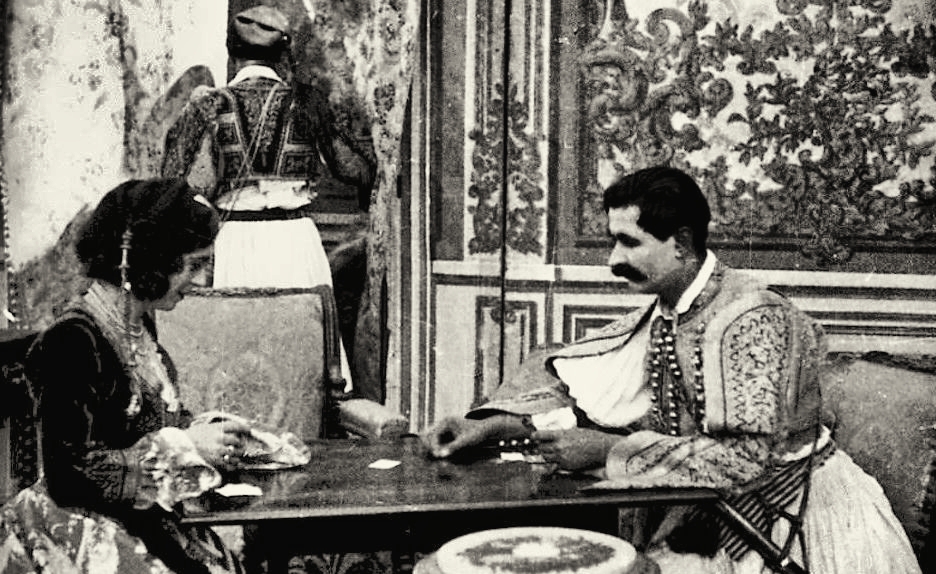

The first feature film that comes to mind of Orsalia-Elena Cassaveti, lecturer and coordinator of the Thematic Department of Cultural and Creative Industries at the Open University of Cyprus, is Mary Pentagiotissa (1929) by Achilleas Madras. Here, through the “director’s skill” of the creator, the myth of the beauty from Pentaga is intertwined with the socio-political life of screen Greece, with the main character entering the palace. “By today’s standards, the film is approaching the limit of fedrosity, but Madras was a pioneer at the time,” Ms. Cassaveti says, and continues: “He put everything into the film, from the events of 1821 to the portrayal of Otho. and her Amalias, while we also see the common people making contact with the palace.”

In “Amaksaki” (1957) by Dinos Dimopoulos, an ethnographic film written by Iakovos Campanellis about the mechanization of society, we also see a fallen aristocrat remembering the big feast she organized and attended by Constantine I – the carriage is also shown here. as a classic vehicle of high society. Ten years later, in Operation Apollo (1968) by George Skalenakis, a German prince falls in love with a Greek guide and is introduced to local tourist folklore.

Otherwise, explains Orsalia-Eleni Cassaveti, in the 60s we find simple written references to the monarchy (for example, in Alekos Sakellarios’ “I will make you queen” and Yannis Dalianidis’s “The Naked Prince”), while the appearance of Konstantinos II and Anna Maria are limited to royal portraits decorating the police station. On television, there are also few examples to show, for example, the series Queen Amalia (1975) with Aliki Vougiouklakis, and indeed the monarchy, as a reference or critical representation, is extremely limited in ancient Greek cinema. “Firstly,” explains Ms. Cassavetes, “because there were censorship mechanisms that pointed to some guidelines in which the Greek nation, national interests, etc. should not be underestimated. Secondly, because the kingdom as a reference is not can offer something to the cinematic narrative, especially when it has a specific specific legitimacy, as, for example, in a melodrama: when we are interested in failed love, the falling in love of Constantine or Frederica in the narrative is at least tasteless.

Coin toss

But what’s going on with New Hellenic Cinema (NEK)? Here one could mention the sensational scene from “Thiaso” by Theodore Angelopoulos (1975), where in the entertainment center on New Year’s Day 1946, two groups “fight” with weapons and songs, and words like “this is how we want and will we bring the king and “we don’t want a king, we want populism, popular rule.” We also note the performance of “Children of Amina” in “Rebetiko” (1983) by Kostas Ferris, as well as the coin toss in “Luf and Variations” (1984) by Nikos Perakis, who judges that after the newsletter of Constantine II will appear not in UNED, but in ” bird” junta.

Other than that, there don’t seem to be many examples. The NEC represents a paradigm shift in narrative and production, very different in terms of expression and criticism from the establishment, but its directors (and although most of them are close to the left) are not so concerned about the monarchy. . “Perhaps for them, it was the parastatal power that provoked the situation, and not the palace,” Orsalia-Elene Cassaveti says, and concludes: “Directors place the monarchy in a context of critical oversight, but they are more interested in highlighting the suffering of others.” repressive mechanisms and violent conditions, especially after the end of the Civil War.

Source: Kathimerini

Ashley Bailey is a talented author and journalist known for her writing on trending topics. Currently working at 247 news reel, she brings readers fresh perspectives on current issues. With her well-researched and thought-provoking articles, she captures the zeitgeist and stays ahead of the latest trends. Ashley’s writing is a must-read for anyone interested in staying up-to-date with the latest developments.