Many European countries have a policy in the field of housing cooperatives, according to a World Bank report. In Austria, 8% of the total housing stock is built or owned by housing cooperatives, which has almost half a million inhabitants. In Romania, the intentions existed only on paper.

In France, 300,000 housing units have already been built by housing cooperatives with a certain regulatory framework.

There were more than 5,000 housing cooperatives in Norway, and 261,250 cooperative members and their families lived in units created by such structures, the World Bank document also shows.

In Germany, until 2011, there were 1,850 housing cooperatives, in which 2,180,000 houses made up 5% of the total housing stock.

Such housing and building cooperatives, although operating in different forms of activity or combination of services provided, pursue a common goal, which is to provide access to a house for purchase or rent at prices below the market. Public authorities, both central and local, support housing cooperatives in various forms: grants or subsidized loans, specialized banking products provided through public housing banks (e.g. in India and Norway), bond guarantees (e.g. in Switzerland), rent reduction subsidies, land plots. on which to build houses, tax benefits, etc.

Housing cooperatives must adhere to strict operating principles (including rent caps) and be regularly audited for compliance as determined by each country’s legislation and housing policy acts. (Sources: Movement Profiles: Cooperative Housing Around the World, Moreau and Pittini (coordinated), 2012; HABICOOP – French Federation of Tenant Cooperatives 2007 and CHI – International Site of Housing Cooperatives (https://www.housinginternational.coop/)

Several changes to the legislative framework paved the way for alternative housing production mechanisms, such as housing cooperatives. The 2005 law governing cooperation in Romania introduced the concept of housing cooperatives, described as associated legal entities that pool resources for the development or management of housing units.

However, this provision still lacks implementation guidance and support tools, and the current practice of housing cooperatives has not been documented and implemented in Romania. The loan guarantee mechanism for first-time home buyers was expanded in 201738 to include the possibility of obtaining a loan through “associative structures that develop collective housing construction.”

There is no data on the extent to which this provision is implemented in practice. The latest changes to the First Home program, approved in September 2020, eliminated funding for these combined structures. Housing and building cooperatives, non-commercial mechanisms for providing affordable housing

Housing rent – how to tax

Officially, the rental housing stock is 3% of the total market in Romania, and unofficially it is estimated to be around 15% nationally. Given the taxation of rental income, tenant legislation and the lack of a mechanism to enforce rental agreements, a large proportion of rents are informal.

Thus, a significant part of the rental market is a source of tax evasion and speculation at the expense of the state and tenants.

Two main factors can contribute to this: eviction rules in favor of tenants and the reluctance of landlords to sign a formal lease because then it becomes difficult to evict a bad tenant. Landlords (even small ones) pay taxes on rental income, and this is an obstacle to creating a formal tenancy.

This does not mean that taxation of rental income is inappropriate, but it can take into account certain threshold values that encourage small owners to formally draw up contracts, the World Bank recommends.

Chaotic development of real estate in our country

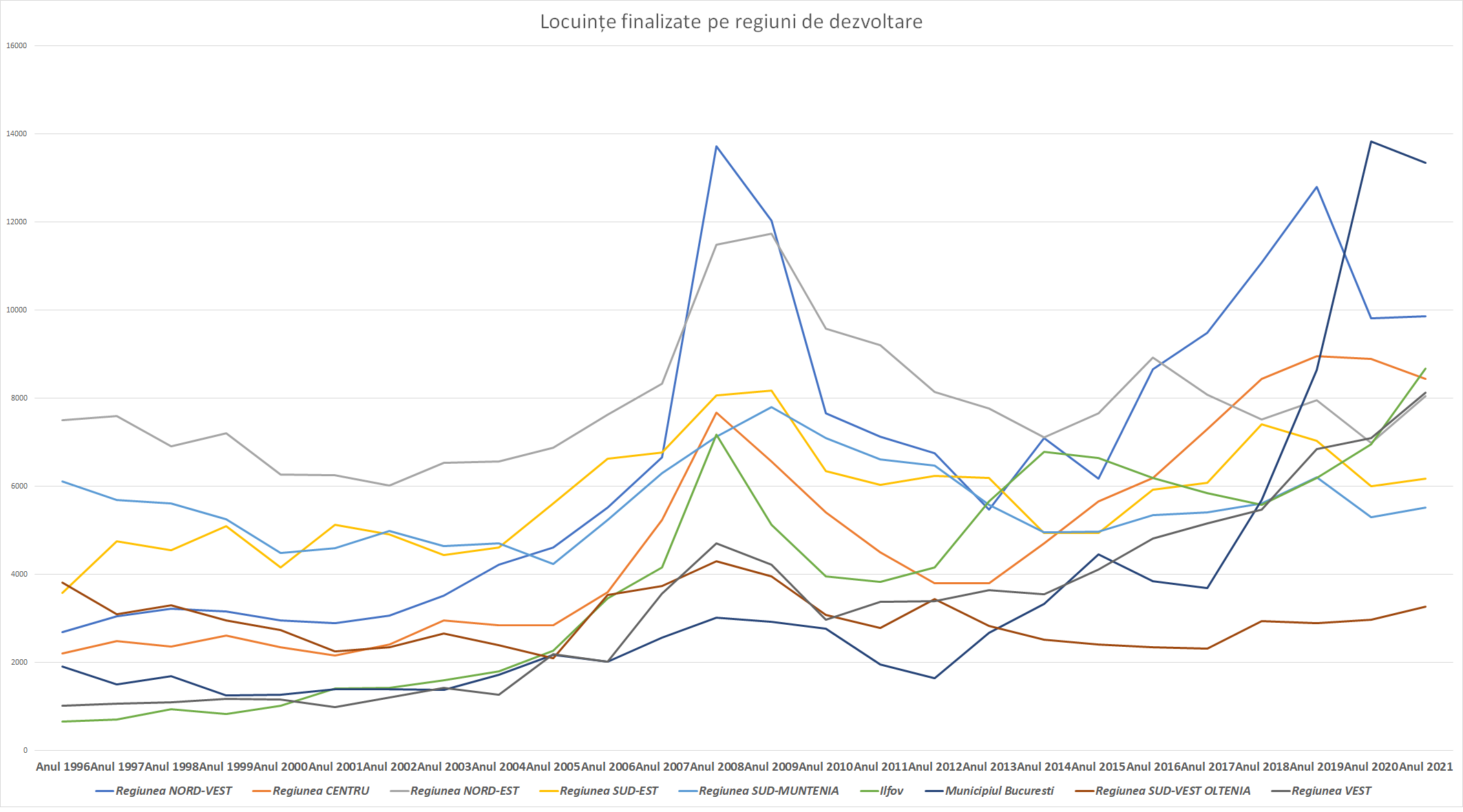

Although economic growth is concentrated in a number of urban areas, the number of completed and for-sale homes (excluding the capital) was more stable in the northwest of the country and significantly lower in Oltenia and Moldova, according to the data. to the Bank World report.

Such dynamics also reflect broader socio-demographic trends of emigration – more pronounced in the eastern parts of Romania – and labor saturation in the western parts of the country, which are better positioned for export-oriented industries. The most dynamic growth in housing supply (construction of new residential buildings) over the past 5 years was recorded in the north-western and central regions. In contrast, the north-eastern region has seen a decrease in housing supply, while the southern regions of Muntenia, Oltenia and Bucharest-Ilfov have moderate growth trends

A closer analysis at the city level shows an increase in housing prices in Western cities: housing in Cluj-Napoca recorded a 75.6% increase in prices over the past 5 years, and Oradea – by 66.4%.

House prices in Cluj-Napoca have risen more than in the capital, even though average incomes in Bucharest are 130% of those in Cluj County, the cited report also shows. This means that urban areas such as Cluj-Napoca are becoming less and less accessible to the majority of the population.

Rising housing prices in Western Romania’s cities pose a challenge to retaining or attracting the residents needed to support a growing local economy and address labor shortages.

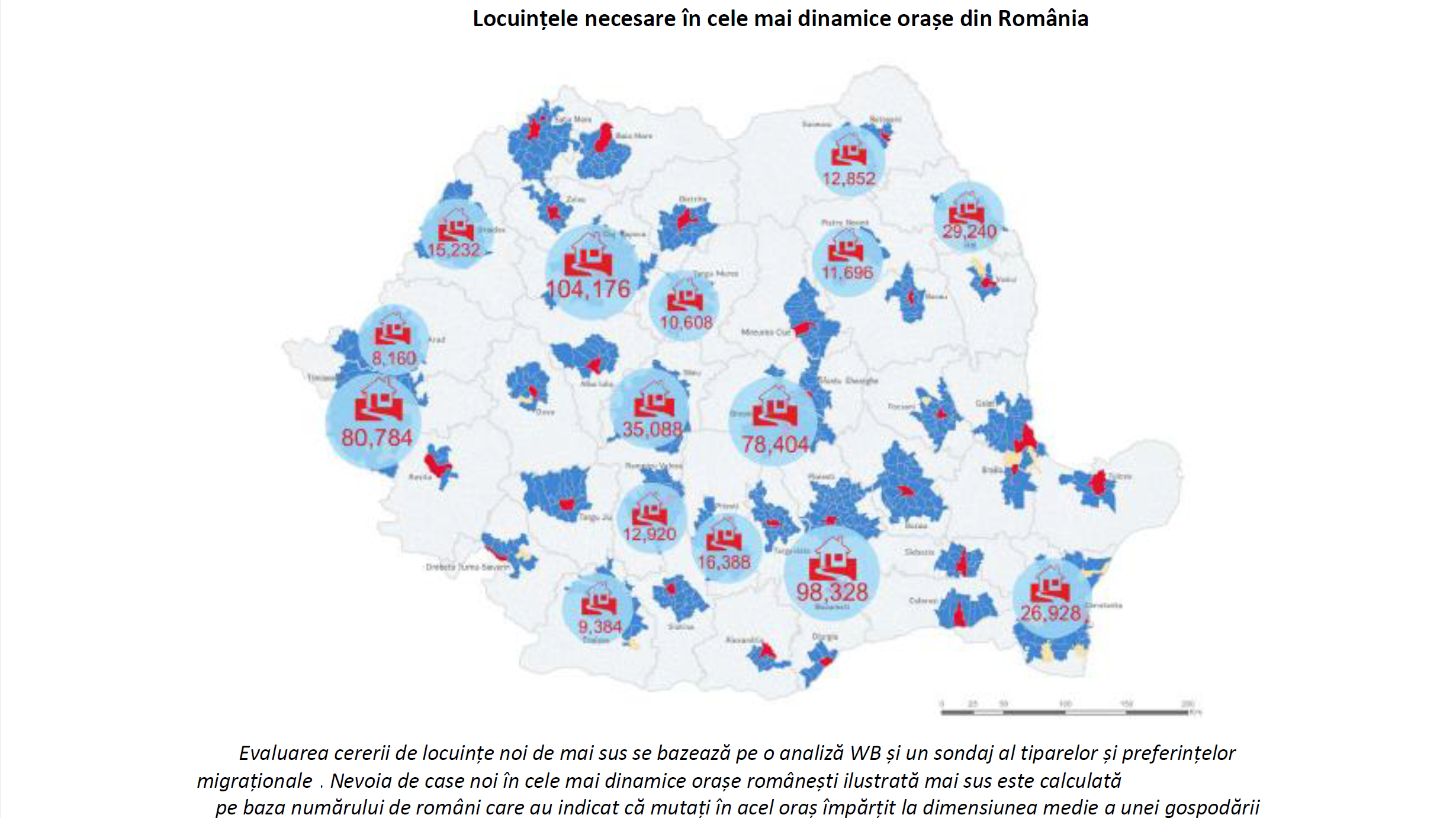

More than 200,000 people could move to Cluj-Napoca and Timisoara, according to previous World Bank research on migration patterns.

Some areas are becoming increasingly attractive for tourism, so housing is seen as a potential investment

For example, cities such as Constanta, located by the sea, or the Transylvanian cities of Sibiu, Brasov and Cluj-Napoca have a strong tendency to list residential units as tourist rentals. The increase in housing demand and housing prices in Romania’s large cities has become the basis of the urban expansion trend.

A third of the houses built in the next 25 years after the revolution were built in the suburbs and suburban areas of Bucharest and the municipalities of the district. Often this rapid suburban residential development has not been preceded or even followed by coherent urban planning and adequate investment in public infrastructure, public amenities and urban transport systems to ensure commuting.

In contrast to the dynamics of the housing market in large cities, in other cities of Romania there is an increase in vacant spaces. Over the past decade, market forces have caused some regions and cities to shrink at an alarming rate, without taking advantage of population growth in other cities with slow and expensive housing.

The overall result is a significant underutilization of housing on the one hand and a shortage of housing on the other. In other words, there are houses, but not necessarily where there are jobs. High levels of home ownership mean that homeowners are often “tied” to where their home is, even if there are jobs elsewhere.

See the full World Bank report here.

Source: Hot News RO

Anna White is a journalist at 247 News Reel, where she writes on world news and current events. She is known for her insightful analysis and compelling storytelling. Anna’s articles have been widely read and shared, earning her a reputation as a talented and respected journalist. She delivers in-depth and accurate understanding of the world’s most pressing issues.