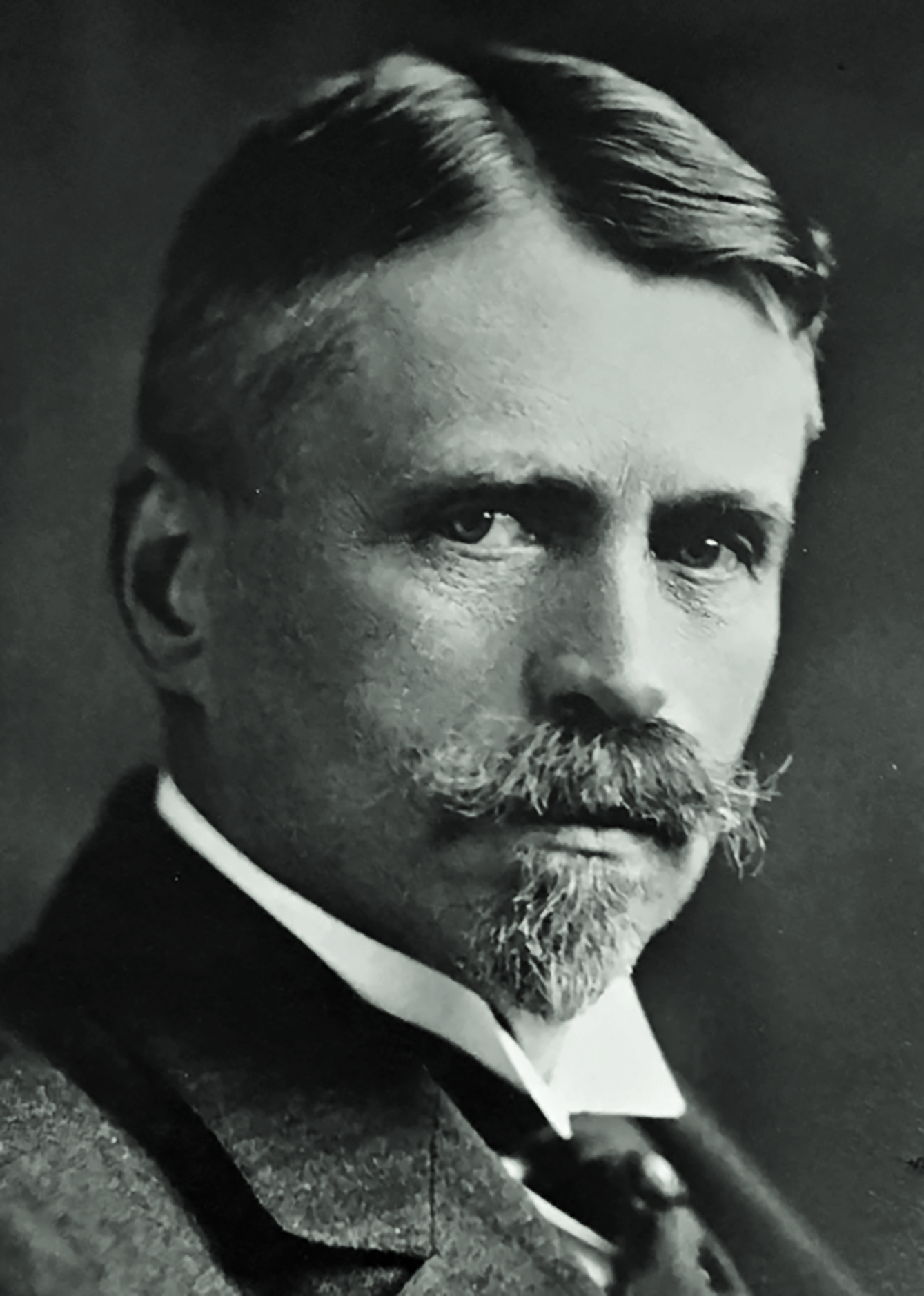

“Tall, leaning on a long cane, usually dressed in a jacket and tie, Horton at first gave the impression of a stern man, but in fact he was a sociable, elderly gentleman, slightly shy, so he enjoyed talking with people of all stripes. life. He spoke fluent Greek and French, as well as decent Italian and Turkish, so he was sure to talk with local officials, priests, shopkeepers, consuls of other countries, shepherds, fig merchants, farmers, dock workers and soldiers. This is how Lou Jureneck (The Great Fire, Psychogios, 2016) describes George Horton, US Consul in Smyrna. Horton arrived in the city in 1919, shortly after the landing of the Greek troops. He did not agree with her, in his report to the State Department (September 27, 1922) he argued that “the Greek landing, under the conditions in which it took place, is a big mistake of Venizelos. […]. To avoid the terrible catastrophe that followed […] there were only two solutions: 1. That the Greeks were never sent to Smyrna. 2. After they (the allies) sent them to their aid and supported them consistently and faithfully.” In fact, he predicted from the outset that the outcome of the campaign would be disastrous, much like the catastrophic outcome of the Athenian invasion of Syracuse two thousand years ago. This parallel showed a deep knowledge of both Greek history and the realities of the region.

Horton was born in 1859 in Fairville, New York. He studied classics at the University of Michigan where he met the Hellenistic professor Martin d’Otz, who passed on his love for the Greek classics. After graduating from university (1878), he was engaged in journalism and worked in the newspapers “Chicago Times Herald” and “Chicago American”.

In 1891 his first collection of poems (“Songs of the Humble”) was published, and in 1897 he published the poem “Aphroesis”, inspired by the Greek folk tradition of fairies. In total, he wrote 18 works, mostly novels, many of which are set in Greece. Whitman admired him as a poet and was praised by many as a novelist. Sensitivity, romance, sincerity of feelings, love for a suffering person – these are some of the elements of his work. “Georgios Horton was not only an excellent poet, writer and American citizen,” wrote his personal physician Alexandros Philadelpheus, “he was above all a noble soul, pulsating with everything high and beautiful in the world.”

Horton came to Athens in 1893 as US consul and remained there until 1897. He returned in 1903 and in 1909 married Ekaterina Sakopoulou. In 1910 he was transferred to Thessaloniki, under Ottoman occupation, the starting point of the Young Turk Revolution (1908), and a year later he moved to Smyrna for the first time as a US consul.

“I not only personally observed, but also confirmed from other witnesses the terrible treatment of the Christian population in the vilayet of Smyrna,” he says in the book The Scourge of Asia (Estia, 2014).

His new post excited him. It was a city associated with Homer and the cultural and philosophical tradition of ancient Ionia. In those years, the first wave of persecution against the Christian population took place. “I myself,” he writes in the book “Asian Plague” (Estia, 2014), “not only personally observed, but also confirmed from other witnesses the terrible treatment of the Christian population in the vilayet of Smyrna, as during the Great War and before her explosion. In 1917, with the departure of the United States to the war, American-Turkish relations were interrupted and Horton returned to Thessaloniki. In the city, which suffered from a devastating fire, he launched a rich charitable work, for which he was honored.

Returning to the post of consul in Smyrna in 1919, he survived the Asia Minor campaign and recorded its dramatic end. “If there was any American or even European who knew what was going on in and around Smyrna, it was Horton,” Yurenek notes. “In Smyrna, as well as inland in the south and east, Horton’s friends and his network of clandestine sources kept him informed. Horton’s network included the Onassis brothers, successful urban tobacconists, but there were many others—Greeks, Armenians, Levantines, and Turks, eyes and ears—on whom he relied to gather information. […] Based on what little information he had already gathered, Horton became increasingly convinced that the Greek occupation of western Anatolia was coming to an end.

Horton reports that after the split of the front, “the city quickly filled with refugees from the hinterland. […] They arrived in Smyrna and on the coast by the thousands. They filled all the churches, schools, courtyards of XEN, HAN and American missionary schools. They even slept outside.” A little later, “defeated, ragged Greek soldiers began to arrive, looking straight ahead like sleepwalkers.”

Already on August 17/30, he began sending urgent telegrams to Washington, reporting on the split of the Greek front and fears that the Kemalist forces would reach Smyrna. He also demanded that destroyers be sent to protect the consulate and citizens. Three days later he returned: “I believe the situation is so dire that it has now become irreversible.”

“The Destruction of Civilization”

“The destruction of Smyrna is nothing but the last act of the ongoing program of extermination of Christianity along and across the old Byzantine Empire, that is, the destruction of the ancient Christian civilization, which in recent years has begun miraculous growth and spiritual renewal. […]. This process of extermination required a significant amount of time. It was distinguished by pre-set goals, a system and great attention to even the smallest details. It was carried out with indescribable brutality, resulting in the destruction of more human lives than any other persecution unleashed in the post-Christian era.” This passage summarizes Horton’s assessment of what happened in Asia Minor in the first decades of the 20th century. It is contained in a bold and well-documented – and from his personal experience – book “The Scourge of Asia”, published in 1926 and caused a great resonance. “I was an eyewitness to the development of this great tragedy, the like of which can hardly be found in world history,” he writes about the death of Smyrna. The book was described as “inappropriate and indecent” by American diplomatic circles, while the British publishers who offered to publish it at the time also turned it down.

Requests for help and many tricks in favor of the Greeks

On September 4 (CE), Horton accepted Stergiadis’ request for U.S. mediation to bring about a peaceful transition from Greek to Turkish occupation. He handed it over to his superiors, offering to accept it. He believed that American mediation with the government in Ankara, which would provide amnesty for the retreating Greek forces, would “prevent the destruction of Smyrna”. The answer he received was that the government “intends to do nothing but send destroyers to Smyrna to help protect American life and property.”

On the same day, he called a meeting with prominent American citizens of Smyrna to discuss what they could do. They returned the next day, after which the Refugee Assistance Committee was formed. Money was collected, flour was purchased, and the committee began distributing food to the refugees. At the same time, he sent requests for assistance to the American Office for Humanitarian Affairs in the Middle East in Istanbul.

Alone among his colleagues who were inactive, he was little in those activities. There were many tricks that could help. “In an unorthodox attempt to save people, he wrote letters granting U.S. protection status to a number of individuals, hoping they would be accepted as tourist visas or protections,” Jurenek says.

On August 31/September 13, 4 days after the Turkish troops entered the city, he gathered his retinue, about 300 Americans and their families, at the Smyrna Theater on the waterfront. Directly opposite was anchored the American destroyer Simpson. “Because it was obvious that the time to evacuate my village was rapidly approaching,” he recalls, “in those few remaining dark hours, I was very busy signing boarding passes for everyone who was eligible for American protection and transportation to Piraeus.” Leaving his office, he took with him twelve old Lydian coins entrusted to him by American archaeologists, and a copy of Leaves of Chloe with Whitman’s own dedication. Shortly thereafter, they boarded the Simpson. “The last image from the ill-fated city of Smyrna,” he writes, “impressed itself in my memory: huge clouds that kept growing and rising into the sky, a narrow beach sheltered by a huge crowd of people with fire behind their backs. and the sea in front of them, and “anchored at a short distance, a powerful fleet of allied ships carelessly watches.”

Arriving in Athens, he set up a settlement for his traveling companions—mostly Greeks who were naturalized Americans who hoped to obtain entry visas to the United States—established a consulate to serve them and provide for their livelihood, and returned to America. USA.

He compared the destruction of Smyrna to the destruction of Carthage by the Romans. “However, there is a feature in the destruction of Smyrna that has no precedent even in the case of Carthage. There was no flotilla of Christian warships there to watch the massacre, for which their governments are responsible. There were no American destroyers in Carthage.”

Such views cost him an unprofitable transfer in 1924 to Budapest. After some time he retired and returned to the United States. He drew his last breath in June 1942.

Source: Kathimerini

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.