Regulars of the Zephyros summer cinema and the old Athenian Oikonomos tavern in Petralona cannot imagine that on the next corner (literally) the road that crosses the popular Troon Street was the setting for the cult film The District 61 years ago. dream” with director and main character Alekos Alexandrakis. The street is Hyperionos Street, and the area is the then Asirmatos slum, a place (an abandoned quarry at the foot of Philopappos) where more than 800 refugee families from Antalya and Asia Minor settled in the 20s. Therefore, the area received the pre-war name “Ta Attaliotika”.

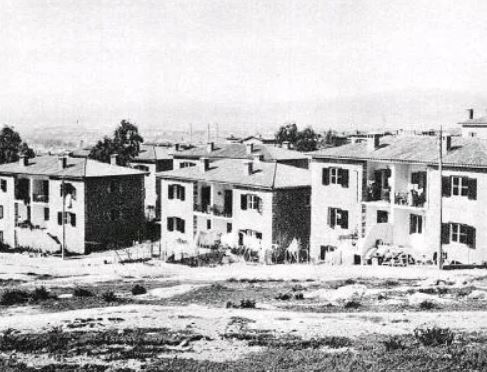

In 1961, when a film was being made in which many residents actively participated in the extras, some of those slums from the first emergency period of the refugee crisis caused by the Asia Minor disaster still survived. The plan to build a large number of decent houses from the hewn stones of the demolished Military School (the so-called “Frederica stones”) and, above all, the construction of the famous modern tenement house designed by Elli Vasilikioti in 1967, marked the final end of the housing adventure, which for this particular area Athens lasted almost half a century.

Such genealogies of refugee settlements are included in the main focus of the research project “Homeacross” (full title “Space, memory and legacy of the 1923 population exchange between Greece and Turkey”), which studies the spatial and architectural dimension of this huge population movement that has changed both the abandoned places, so were the places where the refugees arrived: betting on the absorption of refugee flows from Asia Minor was not a matter of a decade or a generation. It lasted almost the entire 20th century, leaving a strong mark on the architecture, urban planning and social development of places where millions of people lived.

For the first time, Greek and Turkish researchers (mainly architects, but also historians, political scientists, etc.) associated with three different institutions on both sides of the Aegean (Greek Foundation for European and Foreign Policy, Asia Minor of Studies Center and Izmir Institute of Technology , English-speaking public university in Izmir) are working together to study the long-term consequences of such a tense historical moment in space and time. You can see the first fruits of the program at homeacross.eliamep.gr (a trilingual site that will be constantly updated), as well as at the large exhibition of the Benaki Museum “Micra Asia”, which will open in September. 15 in a building on Piraeus street.

The work of the Greek-Turkish group (6 Greeks and 4 Turks make up the main research core) is focused on the consequences of the population exchange in two specific administrative regions, Attica and Smyrna. With the help of basic research tools on the spot in the villages of Ionia, as well as in the vicinity of Athens and Piraeus, with rich archival research in both countries and communication with the descendants of those who were exchanged on both sides, a new, exciting “map” appears “with differences, but also similarities.

The goal of the Greek-Turkish research program is the spatial and architectural dimension of the vast population movement.

The main difference between the two regions is, of course, the intensity of the crisis, which is reflected not only in numbers (the Muslim interchangeable population does not exceed 400,000, while the corresponding figure for the Greek Orthodox population exceeds 1.2 million), but also in the acuteness of the housing problem. Muslims settle in the villages abandoned by the Greeks, and the Greeks have to start from scratch. They are not expected at home. In early December 1922, according to a statement from the Athens City Hall, about 70,000 refugees were living in 130 makeshift camps scattered throughout the city. “When hundreds of new settlements are being planned and built in Greece, in Turkey, the corresponding ones do not exceed a few dozen,” Kalliopi Amigdalu, Ph.D. in history, architectural historian and program leader, tells me. “This does not mean that the Turks did not have their own problems. Many Greek objects have been looted, and residents whose homes were in the radius of military conflicts from 1919 to 1922 are also demanding compensation. In this way, informal competition is created between two different groups of the population. At the same time, cases of corruption are recorded: people who were not refugees claim and occupy the old Greek houses, and the legitimate beneficiaries receive two or even three new objects.

The case of Greece was, of course, a very different story. In Attica, more specifically, refugees found semi-permanent or permanent housing in three main ways: through organized construction by the state, through anarchist self-housing (shacks that were built in any way and at their own expense), and secondly per year through organized individual housing. The 1928 census shows the real numbers: 271,478 refugees are registered in the province of Attica. There are respectively 129,380 refugees registered in the Municipality of Athens (28.1% of the total population) and 101,185 in Piraeus (40.2% of the population).

The first very difficult decade was dominated by organized development, with basic housing units around central communal courtyards built by the state or the Refugee Rehabilitation Committee (CRRC): one-story rooms of minimum space, prefabricated wooden shacks, and, at best, two-story four-story houses. Each room is the first small core that the state builds with the idea that the refugee will find a way to expand it in the future. “In other words, the state prefers emergency architecture, minimal survival infrastructure (without water supply and sewerage systems) with the expectation that the refugee will maintain and expand it,” emphasizes Ms. Amygdalu. By 1930, EAP (which was founded in 1923 with a loan from the League of Nations) had built 6,782 houses in Athens and 5,134 houses in Piraeus, corresponding to 43.16% of EAP’s building activity in the urban regeneration sector throughout the territory.

The picture changes in the second half of the 1920s, when in 1927 a law was passed allowing horizontal construction only for refugee settlements. In two years, the measure will be extended to the entire country, paving the way for the construction of apartment buildings. It is not an exaggeration to say here that the pressure of the acute issue of refugee accommodation is accelerating urban and legislative changes that might otherwise be delayed. Also in 1929, another law was passed encouraging organized independent housing construction through building cooperatives.

In fact, the state distributes plots of land or provides financial support, and the refugees unite in cooperatives and build their own neighborhoods. By 1933, over 320 refugee building cooperatives had been formed, with 10,500 members. The final burial of the illusion of returning to the homes of the ancestors also helped after the signing in 1930 in Ankara of the Pact of Greek-Turkish friendship between Eleftherios Venizelos and Ismet Inonou in the presence of Kemal Atatürk. However, there was a building frenzy in the 1930s, and by 1940 some of the most ambitious housing estates of the time had been built, such as the refugee tenements on Alexandra Avenue, with important architectural touches and in the modernization spirit of the nascent modern movement. But construction fever is not always bloodless. Ms. Amigdala cites Drapetsona as an example: “Clearing began in the area even before 1922, as there was pressure to expand Piraeus to the west, and land was already being bought and sold at the borders of the two districts. With the arrival of the refugees, huge slums suddenly formed, the state was forced to expropriate the territory, resulting in a strong reaction from the investors of the time, and hundreds of cases were taken to the courts, cases that took decades until they were finalized.

I ask Ms. Amygdala what she thinks is the most important legacy of the epic that eventually became the successful integration of the huge wave of refugees from the Asia Minor Holocaust. The discussion turns to the issue of social housing and the role of the welfare state, a role we were most recently reminded of in connection with the pandemic. “In recent decades, as the role of the welfare state has receded and we have been reminded of it by the pandemic and now by the energy crisis, the debate about how Greece has dealt with the refugee problem has taken on new urgency and significance.” And he adds: “Therefore, the history of refugee settlement is to a large extent the history of social housing in Greece, it is an important part of the history of infrastructure, modernization, the welfare state. This is part of the history of modernity and an important part of the history of technical services, that is, the synergy of the state and architecture to intervene in the city. This is a lesson for everyone.”

Source: Kathimerini

James Springer is a renowned author and opinion writer, known for his bold and thought-provoking articles on a wide range of topics. He currently works as a writer at 247 news reel, where he uses his unique voice and sharp wit to offer fresh perspectives on current events. His articles are widely read and shared and has earned him a reputation as a talented and insightful writer.